On March 20, 1951, General Douglas MacArthur received a communication from the U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff stating that the U.S. government was ready to offer peace talks with China and North Korea, before President Truman would allow UN forces to cross the 38th parallel into North Korea. Instead, on March 24, General MacArthur announced an ultimatum, demanding that China withdraw its troops or face the consequences of UN forces advancing into North Korea. In early April 1951, with General MacArthur’s approval, UN forces crossed the 38th parallel, and by April 10, had advanced some 10 miles north to a new line designated the “Kansas Line”.

On April 11, 1951, in a nationwide broadcast, President Truman relieved General MacArthur of his command in Korea, stating that a crucial objective of U.S. government policy in the Korean conflict was to avoid an escalation of hostilities which potentially could trigger World War III, and that “a number of events have made it evident that General MacArthur did not agree with that policy.” General MacArthur had openly advocated an escalation of the war, including directly attacking China, involving forces from Nationalist China (Taiwan), and using nuclear weapons.

General Ridgway, Eighth U.S. Army commander, was named to succeed as Supreme UN and U.S. Commander in Korea. Unlike his predecessor who desired nothing short of total victory, General Ridgway favored a limited war and accepted a divided Korea, and thus worked closely with the U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff and the Truman administration.

(Excerpts taken from Korean War – Wars of the 20th Century: Volume 5 – Twenty Wars in Asia)

Background During World War II, the Allied Powers met many times to decide the disposition of Japanese territorial holdings after the Allies had achieved victory. With regards to Korea, at the Cairo Conference held in November 1943, the United States, Britain, and Nationalist China agreed that “in due course, Korea shall become free and independent”. Then at the Yalta Conference of February 1945, the Soviet Union promised to enter the war in the Asia-Pacific in two or three months after the European theater of World War II ended.

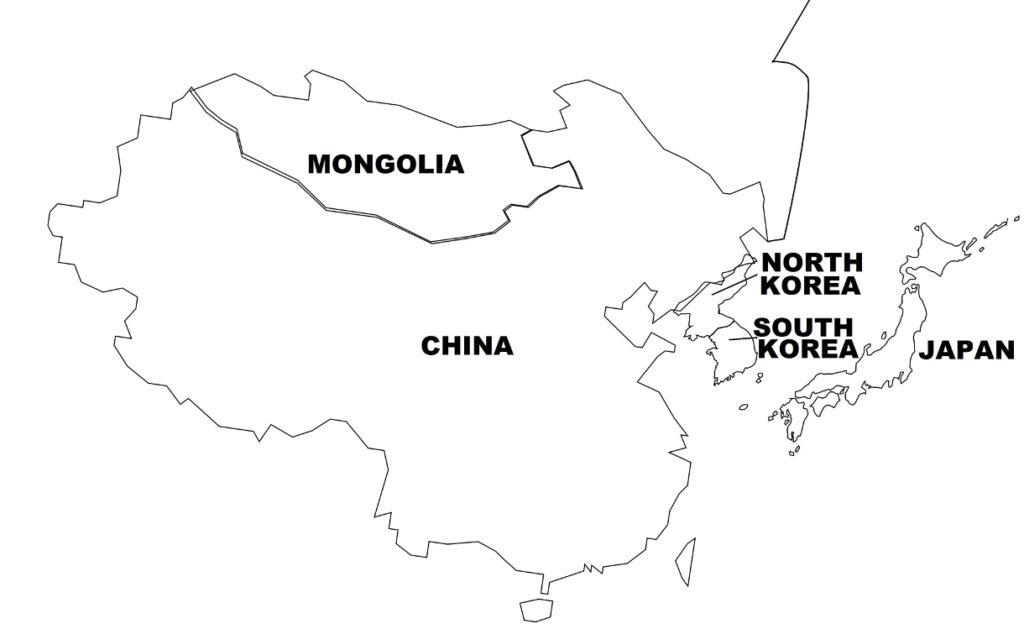

Then with the Soviet Army invading northern Korea on August 9, 1945, the United States became concerned that the Soviet Union might well occupy the whole Korean Peninsula. The U.S. government, acting on a hastily prepared U.S. military plan to divide Korea at the 38th parallel, presented the proposal to the Soviet government, which the latter accepted.

The Soviet Army continued moving south and stopped at the 38th parallel on August 16, 1945. U.S. forces soon arrived in southern Korea and advanced north, reaching the 38th parallel on September 8, 1945. Then in official ceremonies, the U.S. and Soviet commands formally accepted the Japanese surrender in their respective zones of occupation. Thereafter, the American and Soviet commands established military rule in their occupation zones.

As both the U.S. and Soviet governments wanted to reunify Korea, in a conference in Moscow in December 1945, the Allied Powers agreed to form a four-power (United States, Soviet Union, Britain, and Nationalist China) five-year trusteeship over Korea. During the five-year period, a U.S.-Soviet Joint Commission would work out the process of forming a Korean government. But after a series of meetings in 1946-1947, the Joint Commission failed to achieve anything. In September 1947, the U.S. government referred the Korean question to the United Nations (UN). The reasons for the U.S.-Soviet Joint Commission’s failure to agree to a mutually acceptable Korean government are three-fold and to some extent all interrelated: intense opposition by Koreans to the proposed U.S.-Soviet trusteeship; the struggle for power among the various ideology-based political factions; and most important, the emerging Cold War confrontation between the United States and the Soviet Union.

Historically, Korea for many centuries had been a politically and ethnically integrated state, although its independence often was interrupted by the invasions by its powerful neighbors, China and Japan. Because of this protracted independence, in the immediate post-World War II period, Koreans aspired for self-rule, and viewed the Allied trusteeship plan as an insult to their capacity to run their own affairs. However, at the same time, Korea’s political climate was anarchic, as different ideological persuasions, from right-wing, left-wing, communist, and near-center political groups, clashed with each other for political power. As a result of Japan’s annexation of Korea in 1910, many Korean nationalist resistance groups had emerged. Among these nationalist groups were the unrecognized “Provisional Government of the Republic of Korea” led by pro-West, U.S.-based Syngman Rhee; and a communist-allied anti-Japanese partisan militia led by Kim Il-sung. Both men would play major roles in the Korean War. At the same time, tens of thousands of Koreans took part in the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937-1945) and the Chinese Civil War, joining and fighting either for Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalist forces, or for Mao Zedong’s Chinese Red Army.

The Korean anti-Japanese resistance movement, which operated mainly out of Manchuria, was divided along ideological lines. Some groups advocated Western-style capitalist democracy, while others espoused Soviet communism. However, all were strongly anti-Japanese, and launched attacks on Japanese forces in Manchuria, China, and Korea.

On their arrival in the southern Korean zone in September 1948, U.S. forces imposed direct rule through the United States Army Military Government In Korea (USAMGIK). Earlier, members of the Korean Communist Party in Seoul (the southern capital) had sought to fill the power vacuum left by the defeated Japanese forces, and set up “local people’s committees” throughout the Korean peninsula. Then two days before U.S. forces arrived, Korean communists of the “Central People’s Committee” proclaimed the “Korean People’s Republic”.

In October 1945, under the auspices of a U.S. military agent, Syngman Rhee, the former president of the “Provisional Government of the Republic of Korea” arrived in Seoul. The USAMGIK refused to recognize the communist Korean People’s Republic, as well as the pro-West “Provisional Government”. Instead, U.S. authorities wanted to form a political coalition of moderate rightist and leftist elements. Thus, in December 1946, under U.S. sponsorship, moderate and right-wing politicians formed the South Korean Interim Legislative Assembly. However, this quasi-legislative body was opposed by the communists and other left-wing and right-wing groups.

In the wake of the U.S. authorities’ breaking up the communists’ “people’s committees” violence broke out in the southern zone during the last months of 1946. Called the Autumn Uprising, the unrest was carried out by left-aligned workers, farmers, and students, leading to many deaths through killings, violent confrontations, strikes, etc. Although in many cases, the violence resulted from non-political motives (such as targeting Japanese collaborators or settling old scores), American authorities believed that the unrest was part of a communist plot. They therefore declared martial law in the southern zone. Following the U.S. military’s crackdown on leftist activities, the communist militants went into hiding and launched an armed insurgency in the southern zone, which would play a role in the coming war.

Meanwhile in the northern zone, Soviet commanders initially worked to form a local administration under a coalition of nationalists, Marxists, and even Christian politicians. But in October 1945, Kim Il-sung, the Korean resistance leader who also was a Soviet Red Army officer, quickly became favored by Soviet authorities. In February 1946, the “Interim People’s Committee”, a transitional centralized government, was formed and led by Kim Il-sung who soon consolidated power (sidelining the nationalists and Christian leaders), and nationalized industries, and launched centrally planned economic and reconstruction programs based on the Soviet-model emphasizing heavy industry.

By 1947, the Cold War had begun: the Soviet Union tightened its hold on the socialist countries of Eastern Europe, and the United States announced a new foreign policy, the Truman Doctrine, aimed at stopping the spread of communism. The United States also implemented the Marshall Plan, an aid program for Europe’s post-World War II reconstruction, which was condemned by the Soviet Union as an American anti-communist plot aimed at dividing Europe. As a result, Europe became divided into the capitalist West and socialist East.

Reflecting these developments, in Korea by mid-1945, the United States became resigned to the likelihood that the temporary military partition of the Korean peninsula at the 38th parallel would become a permanent division along ideological grounds. In September 1947, with U.S. Congress rejecting a proposed aid package to Korea, the U.S. government turned over the Korean issue to the UN. In November 1947, the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) affirmed Korea’s sovereignty and called for elections throughout the Korean peninsula, which was to be overseen by a newly formed body, the United Nations Temporary Commission on Korea (UNTCOK).

However, the Soviet government rejected the UNGA resolution, stating that the UN had no jurisdiction over the Korean issue, and prevented UNTCOK representatives from entering the Soviet-controlled northern zone. As a result, in May 1948, elections were held only in the American-controlled southern zone, which even so, experienced widespread violence that caused some 600 deaths. Elected was the Korean National Assembly, a legislative body. Two months later (in July 1948), the Korean National Assembly ratified a new national constitution which established a presidential form of government. Syngman Rhee, whose party won the most number of legislative seats, was proclaimed as (the first) president. Then on August 15, 1948, southerners proclaimed the birth of the Republic of Korea (soon more commonly known as South Korea), ostensibly with the state’s sovereignty covering the whole Korean Peninsula.

A consequence of the South Korean elections was the displacement of the political moderates, because of their opposition to both the elections and the division of Korea. By contrast, the hard-line anti-communist Syngman Rhee was willing to allow the (temporary) partition of the peninsula. Subsequently, the United States moved to support the Rhee regime, turning its back on the political moderates whom USAMGIK had backed initially.

Meanwhile in the Soviet-controlled northern zone, on August 25, 1948, parliamentary elections were held to the Supreme National Assembly. Two weeks later (on September 9, 1948), the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (soon more commonly known as North Korea) was proclaimed, with Kim Il-Sung as (its first) Prime Minister. As with South Korea, North Korea declared its sovereignty over the whole Korean peninsula

The formation of two opposing rival states in Korea, each determined to be the sole authority, now set the stage for the coming war. In December 1948, acting on a report by UNTCOK, the UN declared that the Republic of Korea (South Korea) was the legitimate Korean polity, a decision that was rejected by both the Soviet Union and North Korea. Also in December 1948, the Soviet Union withdrew its forces from North Korea. In June 1949, the United States withdrew its forces from South Korea. However, Soviet and American military advisors remained, in the North and South, respectively.

In March 1949, on a visit to Moscow, Kim Il-sung asked Joseph Stalin, the Soviet leader, for military assistance for a North Korean planned invasion of South Korea. Kim Il-sung explained that an invasion would be successful, since most South Koreans opposed the Rhee regime, and that the communist insurgency in the south had sufficiently weakened the South Korean military. Stalin did not give his consent, as the Soviet government currently was pressed by other Cold War events in Europe.

However, by early 1950, the Cold War situation had been altered dramatically. In September 1949, the Soviet Union detonated its first atomic bomb, ending the United States’ monopoly on nuclear weapons. In October 1949, Chinese communists, led by Mao Zedong, defeated the West-aligned Nationalist government of Chiang Kai-shek in the Chinese Civil War, and proclaimed the People’s Republic of China, a socialist state. Then in 1950, Vietnamese communists (called Viet Minh) turned the First Indochina War from an anti-colonial war against France into a Cold War conflict involving the Soviet Union, China, and the United States. In February 1950, the Soviet Union and China signed the Sino-Soviet Friendship, Alliance, and Mutual Assistance Treaty, where the Soviet government would provide military and financial aid to China.

Furthermore, the Soviet government, long wanting to gauge American strategic designs in Asia, was encouraged by two recent developments: First, the U.S. government did not intervene in the Chinese Civil War; and second, in January 1949, the United States announced that South Korea was not part of the U.S. “defensive perimeter” in Asia, and U.S. Congress rejected an aid package to South Korea. To Stalin, the United States was resigned to the whole northeast Asian mainland falling to communism.

In April 1950, the Soviet Union approved North Korea’s plan to invade South Korea, but subject to two crucial conditions: Soviet forces would not be involved in the fighting, and China’s People’s Liberation Army (PLA, i.e. the Chinese armed forces) must agree to intervene in the war if necessary. In May 1950, in a meeting between Kim Il-sung and Mao Zedong, the Chinese leader expressed concern that the United States might intervene if the North Koreans attacked South Korea. In the end, Mao agreed to send Chinese forces if North Korea was invaded. North Korea then hastened its invasion plan.

The North Korean armed forces (officially: the Korean People’s Army), having been organized into its present form concurrent with the rise of Kim Il-sung, had grown in strength with large Soviet support. And in 1949-1950, with Kim Il-sung emphasizing a massive military buildup, by the eve of the invasion, North Korean forces boasted some 150,000–200,000 soldiers, 280 tanks, 200 artillery pieces, and 200 planes.

By contrast, the South Korean military (officially: Republic of Korea Armed Forces), which consisted largely of police units, was unprepared for war. The United States, not wanting a Korean war, held back from delivering weapons to South Korea, particularly since President Rhee had declared his intention to invade North Korea in order to reunify the peninsula. By the time of the North Korean invasion, South Korean weapons, which the United States had limited to defensive strength, proved grossly inadequate. South Korea had 100,000 soldiers (of whom only 65,000 were combat troops); it also had no tanks and possessed only small-caliber artillery pieces and an assortment of liaison and trainer aircraft.

North Korea had envisioned its invasion as a concentration of forces along the Ongjin Peninsula. North Korean forces would make a swift assault on Seoul to surround and destroy the South Korean forces there. Rhee’s government then would collapse, leading to the fall of South Korea. Then on June 21, 1950, four days before the scheduled invasion, Kim Il-sung believed that South Korea had become aware of the invasion plan and had fortified its defenses. He revised his plan for an offensive all across the 38th parallel. In the months preceding the war, numerous border skirmishes had begun breaking out between the two sides.