Immediately following the Gulf War, Kuwait experienced some internal security problems, with crime and lawlessness widespread because of the temporary absence of central authority and the large number of loose firearms that had been left behind by the Iraqi Army. Leaders of the Kuwaiti resistance movement appeared to be in control of the country and pledged their loyalty to Jaber III, Kuwait’s exiled emir. Jubilant youths roamed the streets firing their weapons into the air and rejected calls to turn in their weapons. On March 3, 1991, while still in Saudi Arabia, Jaber III declared martial law in Kuwait (on the advice of U.S. military authorities) and installed Crown Prince Sheik Saad al Abdullah al Sabah as Prime Minister and military governor of Kuwait. Jaber III and his government-in-exile subsequently returned to Kuwait 12 days later, March 15, 1991.

(Taken from Gulf War – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 4)

Aftermath, continuing crisis, and Saddam’s fall from power On March 3, 1991, coalition military leaders, led by General Schwarzkopf, and Iraqi military representatives, led by Iraq’s Defense Minister, General Sultan Hashim Ahmed, held ceasefire talks at Safwan airfield in southern Iraq. The Allies dictated the ceasefire terms, which the Iraqi panel accepted, that contained the following provisions: a separation of forces; release by both sides of prisoners of war and Kuwaiti civilians held in Iraq; withdrawal of coalition forces from occupied Iraqi territory upon signing of the agreement and Iraq’s complying with UN resolutions, ceasing its claims to Kuwait, and agreeing to pay war reparations to Kuwait; and Iraq’s providing information on the location of land mines in Kuwait and sea mines in the Persian Gulf. On March 4, 1991, the Iraqi government officially ratified the ceasefire agreement.

Immediately following the war, Kuwait experienced some internal security problems, with crime and lawlessness widespread because of the temporary absence of real authority and the large number of loose firearms that had been left behind by the Iraqi Army. Leaders of the Kuwaiti resistance movement appeared to be in control of the country and pledged their loyalty to Jaber III, Kuwait’s exiled emir. Jubilant youths roamed the streets firing their weapons into the air and rejected calls to turn in their weapons. On March 3, 1991, while still in Saudi Arabia, Jaber III declared martial law in Kuwait (on the advice of U.S. military authorities) and installed Crown Prince Sheik Saad al Abdullah al Sabah as Prime Minister and military governor of Kuwait. Jaber III and his government-in-exile subsequently returned to Kuwait 12 days later, March 15, 1991.

A military tribunal was set up to prosecute war-time collaborators, who consisted of non-Kuwaitis, i.e. Palestinians, Jordanians and Iraqis, who were sympathetic to the Iraqi occupying forces. Several hundred were arrested and indicted, many of whom were declared guilty and handed down the death sentence or prison terms. Kuwaiti civilians or vigilante groups also attacked suspected collaborators (mostly Palestinians) and captured Iraqi soldiers, beating them up and even killing them.

Martial law, which was planned for three months, was extended for 30 days more and subsequently lifted on June 26, 1991, partly because of international pressure. Military rule thus came to an end, although Jaber III, who had ruled by decree since 1986 after dissolving the constitution and parliament, continued to govern with absolute powers. Kuwaitis also had begun the long and difficult process of rebuilding their devastated country.

In Iraq, despite incurring a crushing defeat in the war, Saddam Hussein continued to hold absolute power of the central government. Iraq’s regular army was incapacitated by the war but the elite Republican Guard, fiercely loyal to Saddam, remained a powerful force equipped with thousands of tanks, armored vehicles, and artillery pieces that had remained in Iraq during the war and had escaped destruction by the coalition air strikes.

The United Nations (UN), which had played a decisive role in the political, economic, and eventually military pressures on Iraq (with twelve UNSC resolutions) that led to the Gulf War, also made great efforts to influence the post-war period. On March 2, 1991, or two days after President Bush announced the Gulf War ceasefire, the UNSC issued Resolution 686, some provisions of which were the following: an end to the war and the carrying out of a ceasefire; release of prisoners of war; and multinational assistance in Kuwait’s reconstruction. It also required Iraq to provide records on the location of mines that had been laid on the ground by the Iraqi Army during the war, as well as information on Iraq’s biological and chemical weapons. Finally, Resolution 686 reaffirmed the UNSC’s previous resolutions against Iraq, e.g. a ban on Iraqi weapons purchases; economic and trade sanctions, excluding items destined for humanitarian needs such as food and medicines.

On April 3, 1991, the UNSC released the more comprehensive Resolution 687, which contained and expanded on Resolution 686, some of which were as follows: First, Iraq was to pay Kuwait U.S. $350 billion in war reparations; Second, to prevent renewed fighting, a demilitarized zone (DMZ) was established, extending 10 kilometers into Iraq and 5 kilometers into Kuwait. A peacekeeping force, called the UN Iraq-Kuwait Observation Mission (UNIKOM) was established and which soon arrived to monitor the DMZ. Third, Iraq was required to stop production of, remove, and destroy its chemical and biological weapons, as well as cease development of nuclear weapons, all of which were collectively referred to as weapons of mass destruction (WMD). To ensure compliance, the UN created the United Nations Special Commission (UNSOM), which was mandated to enter Iraq, and search for and disarm Iraqi WMD.

On March 1, 1991, one day after the Gulf War ended, the Sunni-dominated government of Saddam Hussein faced two separate major local unrests, as Muslim Shiites in southern Iraq and Iraqi Kurds in northern Iraq rose up in rebellion and seized control of large sections of the country. Saddam unleashed his Republican Guard and in a series of retaliatory campaigns, by early April 1991, had quelled the insurgencies, leaving hundreds of thousands dead and over two million fleeing into exile in neighboring countries. On April 5, 1991, the day Saddam declared the uprisings crushed, the UNSC issued Resolution 688, which demanded that the Iraqi government end the repression and human rights violations against its own people

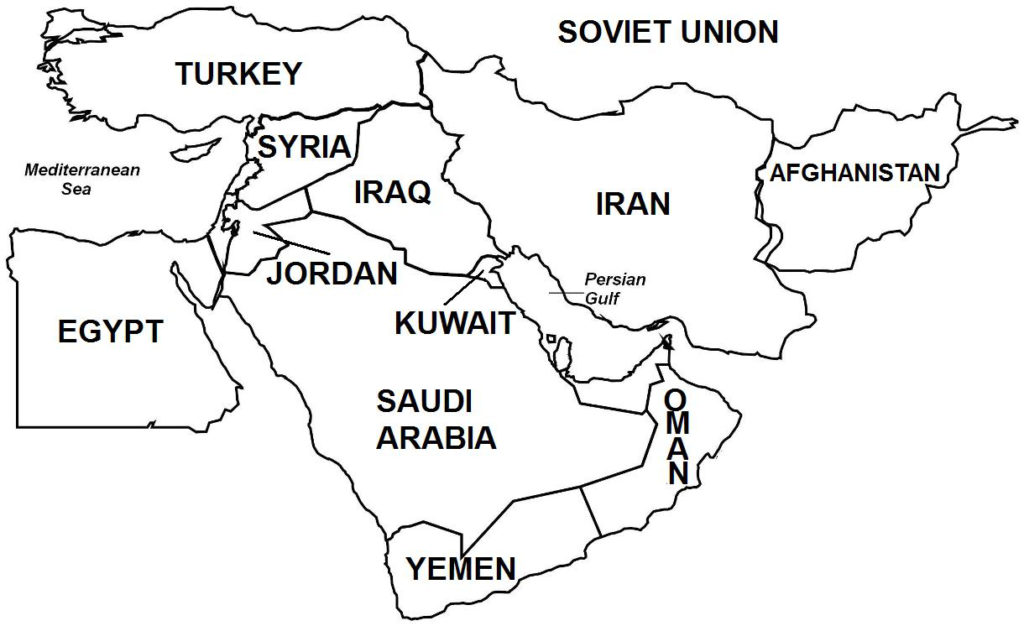

Meanwhile, following the end of the Gulf War, the U.S. government strengthened military ties with Kuwait, Qatar, and Bahrain (Persian Gulf states) and maintained a mainly air force presence in Saudi Arabia, with the consent of King Fahd, the Saudi ruling monarch. As a result of the Iraqi uprisings and to empower UNSC Resolution 688 (i.e. to prevent Saddam from further repressing his own people), the United States, joined by the air forces of Britain and France as a coalition force and operating from air bases in Saudi Arabia, set up a no-fly zone in southern Iraq to protect Iraqi Shiites; Iraqi planes were prohibited from flying inside the no-fly zone and violators faced the risk of being shot down by coalition aircraft. A no-fly zone also had been established earlier (April 1991) by the air forces of the United States, Britain, and Turkey (operating from air bases in Turkey) over the skies in Kurdish regions in northern Iraq in order to allow humanitarian aid to reach the affected civilian populations there.

Meanwhile, the Iraqi government did not cooperate fully with UNSCOM inspectors who were looking for WMD, by withholding records, denying interviews, and restricting access to suspected sites. As a result, in December 1998, the United States and Britain launched Operation Desert Fox, a four-day series of air strikes against Iraqi military sites believed to contain WMD. Thereafter, Saddam refused entry into Iraq of UNSCOM, which also was alleged to have been infiltrated by American and British intelligence agents who spied on Iraq’s military infrastructures and also supposedly gave false information indicating that Iraq possessed WMD. Also as a result of Operation Desert Fox, Iraq challenged the coalition’s no-fly zones, and fired its anti-aircraft guns on and sent its planes to do battle with coalition aircraft. In turn, U.S. and British planes attacked Iraqi air defense systems, resulting in an escalation of air combat activity.

On September 11, 2001, the United States was struck by terrorist attacks, where Islamic militants that were later identified as belonging to al-Qaeda, a terrorist organization, hijacked four commercial planes and crashed two of them into the World Trade Center in New York City and another at the U.S. Department of Defense (Pentagon); the fourth plane, originally targeting Washington, D.C., crashed in a field in Pennsylvania. These events, known as the 9/11 attacks, killed close to 3,000 people, including over 300 firefighters and 70 police officers (and the 227 passengers and crew, and 19 hijackers aboard the planes). In an effort to bring to justice the 9/11 perpetrators, U.S. President George Bush declared a “war on terror”, which soon was supported by most of the international community, and brought Saddam’s regime into closer scrutiny.

On November 8, 2002, the UNSC passed Resolution 1441 that gave Iraq a “final opportunity to comply with its disarmament obligations”. Saddam acquiesced and allowed the UN Monitoring, Verification, and Inspection Commission (UNMOVIC, which was organized and replaced the discredited UNSCOM in December 1999) and the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) to enter Iraq. These agencies’ inspection teams did not find evidence of WMD in Iraq, although in March 2003, UNMOVIC released a report that indicated that Iraq’s cooperation with the WMD inspections was encouraging but must be stepped up further.

Meanwhile, President Bush was determined that only the overthrow of Saddam would remove the threat to regional and international peace. In October 2002, the U.S. Congress passed the Iraq Resolution (officially: “Authorization for Use of Military Force Against Iraq Resolution of 2002”), a joint resolution empowering the United States Armed Forces “to use any means against Iraq”. In March 2003, the British Parliament also passed a motion that authorized military action against Iraq. On March 19, 2003, a U.S.-led coalition force of 200,000 troops (with 145,000 American soldiers), which included contingents from Britain (45,000), Australia (2,000), and Poland (194), invaded Iraq, with the following stated objectives: the overthrow of a regime that possessed and threatened to use WMD, that supported terrorists, and that committed human rights violations.

The invasion drew controversy and widespread criticisms (including large-scale protests in many countries) from a segment of the international community. The United States and Britain had sought UNSC approval but faced a veto threat from permanent members France and Russia. Instead, the U.S. and British governments cited UNSC Resolution 678 and 987, which both contained a clause authorizing the use of all necessary means to enforce Iraq’s compliance with the UNSC resolutions, as sufficient justification for using armed force against Iraq. In the invasion, subsequently known as the Iraq War, the Iraqi Army was soundly defeated; Saddam was overthrown and went into hiding, and was subsequently found and arrested, tried, and executed for crimes against humanity. In subsequent searches by the Iraq Survey Group, an investigative agency set up by the coalition partners, no WMD were found in Iraq.