General Dwight D. Eisenhower and the Allied High Command believed that attempting to cross the Rhine on a broad front would lead to heavy losses in personnel, and so they planned to concentrate Allied resources to force a crossing on the north in the British sector. Here also lay the shortest route to Berlin, whose capture was definitely the greatest prize of the war. Beating out the Soviets to Berlin was greatly desired by Prime Minister Churchill and the British High Command, which at this point, the British and American planners believed could be achieved. With Allied focus on the British sector in the north, U.S. 12th and 6th Army Groups to the south were tasked with making secondary attacks in their sectors, tying down German troops there and thus aiding the British offensive.

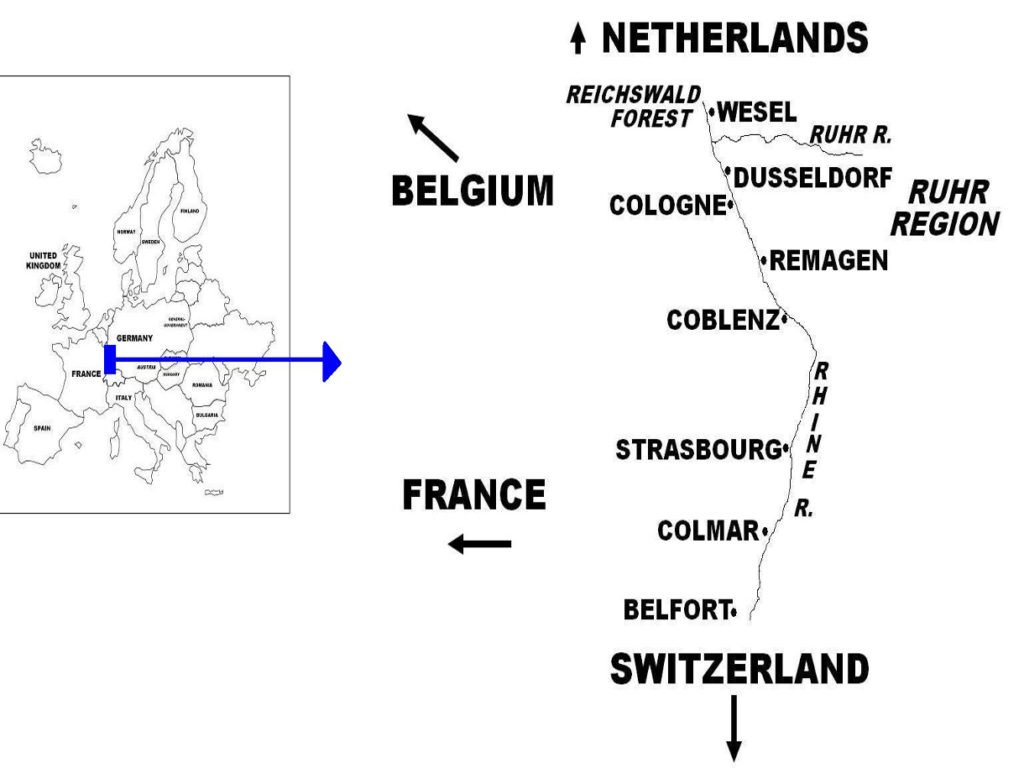

Then on March 7, 1945, elements of U.S. 1st Army (part of U.S. 12th Army Group), upon reaching the Rhine’s west bank at Remagen, came upon a railroad bridge that was still standing and undefended. The Americans, taking advantage of this unexpected opportunity, rushed 25,000 troops in six divisions and large numbers of tanks and artillery pieces to the other side before the bridge collapsed on March 17. By then, U.S. 1st Army had built two tactical bridges, and had established a secure bridgehead on the eastern side some 40 km wide and 15 km long. The Germans, during their retreat, had systematically destroyed the fifty bridges across the whole length of the Rhine, but had failed to detonate the charges on the Remagen Bridge.

(Taken from Defeat of Germany in the West: 1944-1945 – Wars of the 20th Century – World War II in Europe)

On March 22, 1945, U.S. Third Army also crossed the Rhine, at Oppenheim and soon at two other points further north. General Patton, the U.S. 3rd Army commander, had rushed the crossings with little preparations, purposely to deny his rival General Montgomery the honor of being the first to force an opposed crossing of the Rhine. To the south, U.S. 7th Army crossed at Worms and the French at Germersheim.

On March 23, 1945, General Montgomery and 21st Army Group launched Operation Plunder, the forcing of the Rhine at Rees, Wesel, and south of the Lippe River. As was typical with General Montgomery, the operation was launched after thorough preparation and heavy concentration of forces. The offensive was made with the largest airborne assault in history (Operation Varsity, involving 16,000 Allied paratroopers in 3,000 planes and gliders), and massive air and artillery bombardment of German positions before the amphibious crossing of the Rhine by the ground forces. The operation was a great success, overwhelming the German defenders. By late March 1945, the Allies had established a chain of bridgeheads on the Rhine’s eastern bank and were threatening to break out into the German heartland.

On March 28, 1945, General Eisenhower announced that the capture of Berlin was not anymore the main goal of the Western Allies, for the following reasons. First, the Soviet Red Army would clearly reach Berlin first, as it was poised at the Oder River just 30 miles (48 km) of the German capital, while the Western Allies at the Rhine were over 300 miles (480 km) from Berlin. Second, the breakthrough in the south would allow the Western Allies, particularly the U.S. forces, to rapidly fan out into the heart of Germany, which would break German morale and bring a quick end to the war. Third, SHAEF priority was now to capture the Ruhr region, Germany’s industrial heartland, to destroy German’s weapons production facilities and incapacitate Germany’s ability to continue the war.

Under these revised objectives, the three Allied Army Groups advanced into Germany and then into Central Europe. In the north, the British advanced toward Hamburg and the Elbe River, and met up with Soviet forces at Wismar in the Baltic coast on May 2, 1945, while the Canadians secured the Netherlands and northern German coast. To the south of the British, on March 7, U.S. 9th and 1st Armies attacked the Ruhr region in a pincers movement, leading to the last large-scale battle in the Western Front. On April 4, the pincers closed, and U.S. forces systematically destroyed the trapped German Army Group B inside the Ruhr pocket. On April 21, the pocket was cleared and the Americans captured over 300,000 German soldiers, this unexpected massive German defeat surprising the Allied High Command. As a result of this catastrophe, German Army Group B commander General Walther Model committed suicide, while concerted German defense of the Western Front effectively ceased. Other elements of U.S. 9th and 1st Armies had also advanced further east, and on April 25, 1945, contact was made between American and Soviet forces at the Elbe River.

Further to the south, General Patton’s 3rd Army advanced into western Czechoslovakia and southeast for eastern Bavaria and northern Austria. U.S. 6th Army Group (U.S. 7th Army and the French Army) turned south into Bavaria, Austria, and northern Italy, with the isolated German garrisons at Heilbronn, Nuremberg, and Munich putting up some stiff resistance before surrendering.

On April 30, 1945, Hitler committed suicide, and three days later, Berlin fell to the Red Army. As per Hitler’s last will and testament, governmental powers of the now crumbling German state passed on to Admiral Karl Doenitz, head of the German Navy, who at once took steps to end the war. On May 2, German forces in Italy and western Austria surrendered to the British, and two days later, the Wehrmacht in northwest Germany, the Netherlands and Denmark surrendered, also to the British, while on May 5, German forces in Bavaria and southwest Germany surrendered to the Americans. At this time, isolated German units facing the Soviets were desperately trying to fight their way to Western Allied lines, hoping to escape the punitive wrath of the Russians by surrendering to the Americans or British.

On May 7, 1945, General Alfred Jodl, German Armed Forces Chief of Operations, signed the instrument of unconditional surrender of all German forces at Allied headquarters in Reims, France. A few hours later, Stalin expressed his disapproval of certain aspects of the surrender document, as well as its location, and on his insistence, another signing of Germany’s unconditional surrender was held in Berlin by General Wilhelm Keitel, chief of German Armed Forces, with particular attention placed on the Soviet contribution, and in front of General Zhukov, whose forces had captured the German capital.

Shortly thereafter, most of the remaining German units surrendered to nearby Allied commands, including Army Group Courland in the “Courland Pocket”, Second Army Heiligenbeil and Danzig beachheads, German units on the Hel Peninsula in the Vistula delta, Greek islands of Crete, Rhodes, and the Dodecanese, on Alderney Island in the English Channel, and in Atlantic France at Saint-Nazaire, La Rochelle, and Lorient.