On March 2, 1969, Soviet border troops were sent to Damansky/Zhenbao Island to expel 30 Chinese soldiers who had landed on the island. Unbeknown to the Soviets, a large Chinese force, (300 soldiers, according to the Soviets) which was hidden and waiting in ambush in the nearby forest, opened fire on the Soviets. Fighting then broke out, with other units from both sides joining the fray. Chinese units used artillery and small arms fire from their side of the Ussuri River, while the Soviets sent reinforcements to Damansky/Zhenbao Island from their side of the river.

(Taken from Sino-Soviet Border Conflict – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 5)

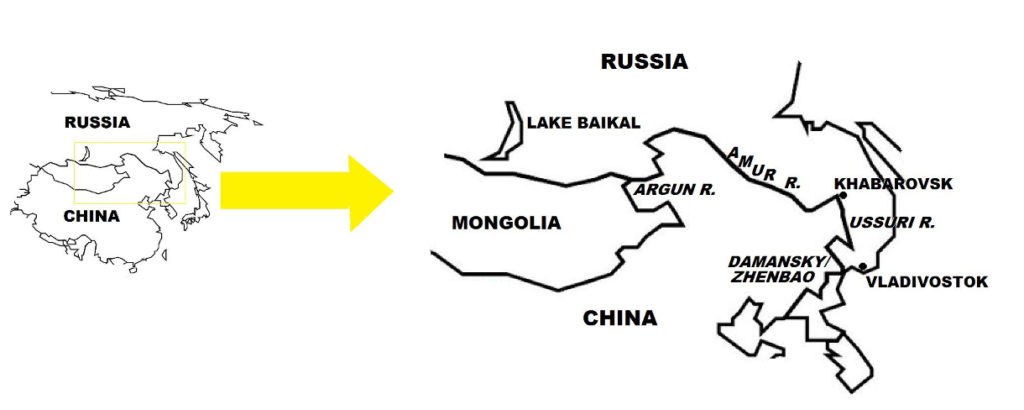

What became the trigger for the escalation of border clashes that nearly led to total war between China and the Soviet Union was the disputed but nondescript Damansky Island (Zhenbao Island to the Chinese), a small (0.74 square kilometers) 1½-mile long by ½-mile wide island located in the Ussuri River between the Soviet bank in the east and the Chinese bank in the west. By the terms of a treaty signed in the 19th century, Damansky/Zhenbao Island belonged to the Soviet Union. The island was uninhabited, and also experienced flooding from seasonal rains. Both the Chinese and Soviets regularly sent patrols to reconnoiter the island.

During border negotiations in 1964, the Soviet Union agreed to cede the island to China, but then retracted this offer when talks broke down. Thereafter, the island became a flashpoint for armed clashes. In March 1969, China accused the Soviet Union of intruding into Damansky/Zhenbao Island sixteen times during a two-year period in January 1967-March 1969. In December 1968 and again in January 1969, Soviet border guards used non-lethal force to expel Chinese patrols from the island. More border incidents occurred in February 1969.

Then on March 2, 1969, Soviet border troops were sent to Damansky/Zhenbao Island to expel 30 Chinese soldiers who had landed on the island. Unbeknown to the Soviets, a large Chinese force, (300 soldiers, according to the Soviets) which was hidden and waiting in ambush in the nearby forest, opened fire on the Soviets. Fighting then broke out, with other units from both sides joining the fray. Chinese units used artillery and small arms fire from their side of the Ussuri River, while the Soviets sent reinforcements to Damansky/Zhenbao Island from their side of the river.

A Chinese military report after the incident stated that the Soviets fired the first shots. More recent information indicates that the Chinese military planned the incident, and used elite army units with battle experience to ambush the Soviet patrol. In this way, China hoped to retaliate for the many Soviet provocations, and also to signal that China would not be intimidated by the Soviet Union.

The two sides released different casualty figures for the Damansky/Zhenbao incident, although the Soviets may have suffered greater losses, at 59 dead and 94 wounded. Both the Chinese and Soviets claimed victory. The two sides also raised strong diplomatic protests against the other, accusing the other side of starting the incident. The Soviet Union accused China of being “reckless and provocative”, while China warned that if the Soviet Union continued to “provoke armed conflicts”, China would respond with “resolute counter-blows”.

Sensationalist news reports by the media from the two sides stirred up the general population in both countries. On March 3, 1969 in Beijing, large protests were held outside the Soviet Embassy, and Soviet diplomatic personnel were harassed. In the Soviet Union, demonstrations were held in Khabarovsk and Vladivostok. In Moscow, angry crowds hurled stones, ink bottles, and paint at the Chinese Embassy.

On March 11, 1969 in Beijing, demonstrators besieged the Soviet Embassy in protest for the attack on the Chinese Embassy. Then when Soviet media reported that captured Russian soldiers during the Damansky/Zhenbao incident had been tortured and executed, and their bodies mutilated, large demonstrations consisting of 100,000 people broke out in Moscow. Other mass assemblies also occurred in other Russian cities.

On March 15, 1969, a second (and larger) clash broke out in Damansky/Zhenbao Island, where both sides sent a force of regimental strength, or some 2,000-3,000 troops. The Chinese claimed that the Soviets fielded one motorized infantry battalion, one tank battalion, and four heavy-artillery battalions, or a total of over 50 tanks and armored vehicles, and scores of artillery pieces. The two sides again claimed victory in the 10-hour battle, and also accused the other side of firing the first shots. Both sides suffered heavy casualties.

The Soviets lost a number of armored vehicles, and failed to expel the Chinese from the island. On March 17, 1969, some 70 Soviet soldiers who were sent to retrieve a disabled T-62 tank were forced to retreat. The Chinese subsequently recovered the Soviet tank and transported it to Beijing where it was put on public display. Casualty figures for the March 15-17 battles are disputed. The Soviets place their own losses at 58 dead and 94 wounded. The Chinese place their losses at 29 dead, 62 wounded, and one missing. Foreign independent sources provide much higher combined total casualty figures, from 800 to 3,000 soldiers killed for both sides.

As in the first incident (March 2), more recent Chinese sources indicate that the Chinese Army had prepared for the second encounter (March 15). Chinese authorities had anticipated that the Soviets would return in force. The Chinese Army therefore sent a greater number of Chinese elite units, and fortified its side of the island with land mines. With these preparations, the Chinese succeeded in repelling the Soviets, who had attacked using armored units. After the encounter, the Soviets began an extended artillery barrage of Chinese positions across the river, and hit targets as far as seven kilometers inside China.

The two incidents generated different reactions in the Chinese and Soviet governments. In China, Mao made efforts to prevent the crisis from escalating further. He ordered Chinese border troops not to retaliate to the Soviet artillery shelling of Chinese positions in Damansky/Zhenbao Island, and at the Chinese side of the Ussuri River. In Moscow, the Soviet government was thoroughly provoked by the two incidents, viewing them as a direct challenge from China.

However, Soviet authorities were divided as to the appropriate response. The Foreign Ministry called for caution, but the military wanted aggressive action. On May 24, 1969, because of continued border incidents by Russian troops, China filed a diplomatic protest, accusing the Soviet Union of provoking war. On May 29, the Soviet government threatened to go to war with China, but also called for talks between the two sides.

As tensions increased, so did troop deployment to the disputed regions. Soon, 800,000 Chinese and 700,000 Soviet troops were deployed at the border. The Soviets continued to initiate border incidents, apparently to provoke a wider conflict. On August 13, 1969 in the Tieliketi Incident, 300 Soviet troops, supported by air and armored units, entered China’s Tieliketi area, located in Xinjiang region, in the western border. There, they ambushed and killed 30 Chinese border guards.

By now, the Soviet Union was preparing for war, and increased its forces in Mongolia and carried out a large military exercise in the Far East. Soviet authorities notified Eastern Bloc countries that Russian planes could launch an air strike on China’s nuclear facility in Lop Nur, Xinjiang. In Washington, D.C., a Soviet diplomatic official, while dining with a U.S. State Department officer, broached the planned Soviet attack on China’s nuclear site, to gauge American reaction. The U.S. official reacted negatively, and subsequent U.S. warnings of intervening militarily if the Soviet Union attacked China, would have far-reaching repercussions in the ongoing Cold War.

Meanwhile in Beijing, Chinese authorities were concerned about the growing threat of war with the Soviet Union. Despite appearing defiant, and warning Russia that it too had nuclear weapons, China was unprepared to go to war, and its military was far weaker than that of the Soviet Union. Exacerbating China’s position was its ongoing Cultural Revolution, which was causing serious internal unrest.