In September 1969, conservative politicians, frustrated at the continuing Vietnamese occupation of eastern Cambodia, made plans to overthrow Sihanouk. Then in March 1970, while Sihanouk was on a trip outside the country, anti-Vietnamese demonstrations broke out in Phnom Penh. The protests turned violent, with mobs entering and looting the embassies of North Vietnam and Provisional Revolutionary Government of South Vietnam (the Viet Cong’s government-in-exile).

Taking advantage of the widespread anti-Vietnamese sentiment among Cambodians, Prime Minister Lon Nol closed down Sihanoukville to communist-flagged vessels. Lon Nol also voided Sihanouk’s trade agreement with North Vietnam, and on March 12, 1970, he demanded that Vietnamese forces leave Cambodian territory within 72 hours.

Lon Nol initially was unwilling to support the plot to overthrow Sihanouk. But on March 18, 1970, he convened the National Assembly, which in a 92-0 non-confidence vote, declared its ceasing recognition of Sihanouk as Cambodia’s head of state, and deposed him. Subsequently in October 1970, Lon Nol declared the end of the Kingdom of Cambodia. In its place, he formed the Khmer Republic, taking the position of president. The new regime was firmly pro-American, and U.S. advisers, weapons, and military equipment soon arrived.

(Taken from Cambodian Civil War – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 5)

Meanwhile in Cambodia, Sihanouk sought to stay away from the conflict in Vietnam by maintaining a policy of non-alignment (which he called “extreme neutrality”) for Cambodia. He took part in the 1955 Bandung Conference (in Bandung, Indonesia) which led to the formation of the Non-Aligned Movement.

But by the second half of the 1950s, Sihanouk had also established friendly ties with China, particularly to serve as a deterrent against Cambodia’s historical ethnic enemies, the Thais and Vietnamese, and also because he viewed the U.S. presence in Indochina as temporary, when considered over the long term, just as it had been for the French. In an agreement made in February 1956, Cambodia received economic aid from China. In 1958, Cambodia and China established diplomatic relations. Two years later, 1960, they signed the Treaty of Friendship and Non-aggression.

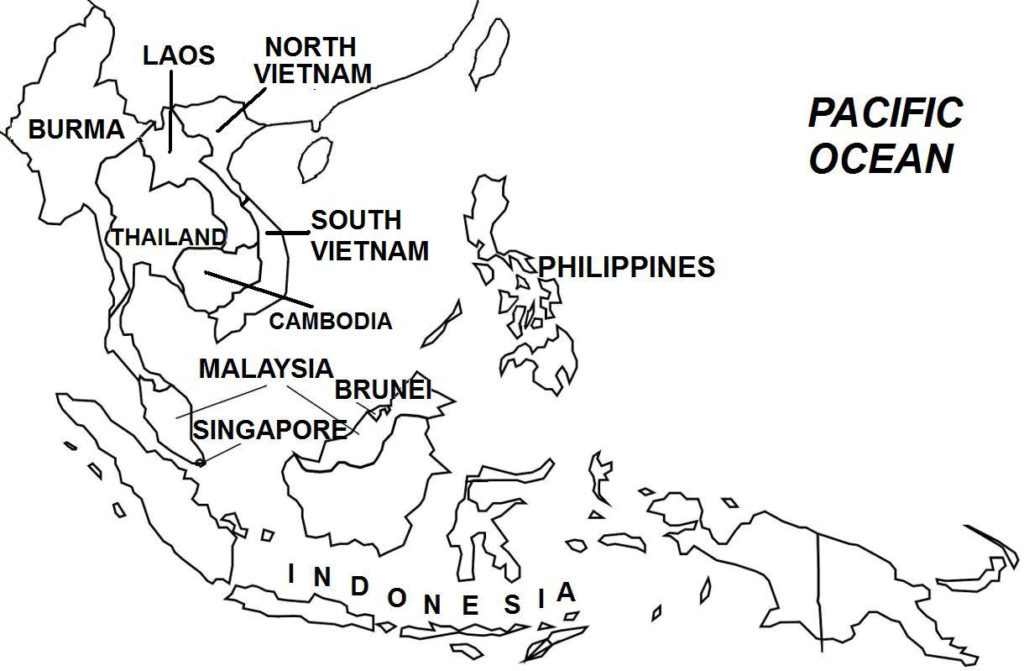

Thailand and South Vietnam, Cambodia’s neighbors on either side, viewed the Cambodian government with deep suspicion, believing Sihanouk to be aligning with the communists. Then when two attempts were made on Sihanouk (in January and August 1959), he accused South Vietnam of plotting his assassination.

Invariably intertwined with Cambodia’s foreign relations were the ancient Cambodians’ historical animosity with their neighbors, the Thais and Vietnamese. In particular, during the 1800s, the Vietnamese had sought to eradicate the Indian-influenced Cambodian culture and introduce the Chinese-influenced Vietnamese culture to the Cambodians. The Vietnamese also annexed a large section of Khmer territory, specifically the Mekong Delta of present-day Vietnam. As a result, later-day Cambodians viewed the Vietnamese with suspicion and resentment, and these sentiments would play a part in the coming civil war.

While establishing diplomatic relations with China, Sihanouk also maintained friendly ties with the West, particularly the United States. In 1955, Cambodia and the United States signed a military agreement where the U.S. government provided weapons to Cambodia’s military (which was called FARK, Forces Armées Royales Khmères). By the early 1960s, the Americans were providing military support equivalent to 30% of Cambodia’s defense appropriations.

In the mid-1960s, Cambodia’s neutrality was increasingly being undermined, first because North Vietnam had extended the Ho Chi Minh Trail (its logistical route to South Vietnam) across eastern Cambodia, and second, to counteract this North Vietnamese action, U.S. planes conducted surveillance and bombing operations along the Ho Chi Minh Trail, and South Vietnamese forces occasionally entered Cambodia to pursue the Viet Cong.

Sihanouk and his declared non-alignment also came under U.S. scrutiny when he signed agreements with China and North Vietnam. In these agreements, Cambodia allowed the following stipulations: that the North Vietnamese and the Viet Cong could occupy eastern Cambodia; that the port of Sihanoukville (Figure 7) would be opened to communist bloc ships that supplied war materials for the Viet Cong; and that the North Vietnamese would be allowed to use a road network across Cambodia to transport the supplies from Sihanoukville to South Vietnam (this route became known in the West as the Sihanouk Trail).

In the early 1960s, as Cambodia moved toward establishing closer ties with China and North Vietnam, so did its relations with the United States deteriorate. The decline in Cambodian-American relations resulted from a number of factors: First, Sihanouk began to fear that a stronger Cambodian military (which was supplied with U.S. weapons), would soon threaten his government; Second, he believed that the United States was involved in the assassination plots against him; and Third, he suspected that the U.S. military were supporting the Khmer Serei, a right-wing guerilla group that was fighting an insurgency war against the Cambodian government. In November 1963, Sihanouk cut U.S. aid to Cambodia, and in May 1965, diplomatic relations between the two countries broke down.

In the September 1966 Cambodian parliamentary elections, right-wing candidates of the ruling Sangkum party won most of the seats in the National Assembly, leading to the Cambodian government shifting to the right. Pro-U.S. General Lon Nol became the new Prime Minister. Also by the second half of the 1960s, Sihanouk again turned his foreign policy toward the West, for the following reasons: First, Cambodia’s relations with China and North Vietnam did not produce clear economic benefits to Cambodia; Second, the loss of American aid was negatively affecting the Cambodian economy; and Third, this new foreign policy would balance the rightist and leftist elements in Cambodia’s deeply politicized government. In June 1969, following the U.S. government’s promise to respect Cambodia’s neutrality and sovereignty, diplomatic relations between Cambodia and the United States were restored.

By this time, the right-wing faction in the Cambodian government had lost confidence in Sihanouk’s capacity to resolve the country’s many political and economic problems. In September 1969, conservative politicians, frustrated at the continuing Vietnamese occupation of eastern Cambodia, made plans to overthrow Sihanouk. Then in March 1970, while Sihanouk was on a trip outside the country, anti-Vietnamese demonstrations broke out in Phnom Penh. The protests turned violent, with mobs entering and looting the embassies of North Vietnam and Provisional Revolutionary Government of South Vietnam (the Viet Cong’s government-in-exile).

Taking advantage of the widespread anti-Vietnamese sentiment among Cambodians, Prime Minister Lon Nol closed down Sihanoukville to communist-flagged vessels. Lon Nol also voided Sihanouk’s trade agreement with North Vietnam, and on March 12, 1970, he demanded that Vietnamese forces leave Cambodian territory within 72 hours.

Lon Nol initially was unwilling to support the plot to overthrow Sihanouk. But on March 18, 1970, he convened the National Assembly, which in a 92-0 non-confidence vote, declared its ceasing recognition of Sihanouk as Cambodia’s head of state, and deposed him. Subsequently in October 1970, Lon Nol declared the end of the Kingdom of Cambodia. In its place, he formed the Khmer Republic, taking the position of president. The new regime was firmly pro-American, and U.S. advisers, weapons, and military equipment soon arrived.

Meanwhile, the deposed Sihanouk took up residence in Beijing, China, where Mao Zedong’s government granted him political asylum. In Phnom Penh in the days after the coup, tens of thousands of Cambodians, mainly peasants with whom Sihanouk was extremely popular, launched large protest demonstrations in Kampong Cham, Takeo, and Kampot Provinces. Some 40,000 farmers marched on Phnom Penh demanding that Sihanouk be restored to power. The demonstrations turned violent when security forces dispersed the crowds, killing hundreds of protesters. Violence also broke out against ethnic Vietnamese living in Cambodia. In the countryside, Cambodians massacred hundreds of ethnic Vietnamese.

Lon Nol launched a program to strengthen Cambodia’s armed forces. Many civilians signed up to join the military, with many recruits motivated by the sole desire to fight and expel the Vietnamese Army from eastern Cambodia. As a result of heavy recruitment, the Cambodian Army grew from 35,000 in early 1970, to a peak of 250,000 in 1974.

Sihanouk’s overthrow and the emergence of a pro-U.S. government would have profound effects for Cambodia, particularly with regards to the ongoing Vietnam War. The United States, long restrained by Cambodia’s official neutrality, increased bombing operations on North Vietnamese Army/Viet Cong bases in eastern Cambodia, this aerial campaign extending from May 1970 – August 1973. U.S. bombing had actually started one year earlier (under Operation Menu), in March 1969, in which Sihanouk may have given his tacit consent. The bombings were very intense, in total, over 500,000 tons of ordnance were dropped (equivalent to 30% of the 1.5 million tons of all bombs that U.S. planes dropped in Europe during World War II). Various estimates place the number of Cambodian civilian casualties caused by American bombing at between 40,000 and 150,000 killed. The U.S. bombings, together with the ground fighting, destroyed much of eastern Cambodia, forcing hundreds of thousands of civilians to flee to Phnom Penh, the capital. Phnom Penh soon grew to a population of 2 – 2½ million by 1975, from 600,000 in 1970.

In April 1970, in a major offensive known as the Cambodian Campaign, American and South Vietnamese forces crossed the border from South Vietnam into eastern Cambodia aimed at destroying North Vietnamese Army/Viet Cong military bases and supply depots along the Ho Chi Minh Trail. The success of this operation was deemed crucial to the withdrawal of U.S. troops from South Vietnam in line with the American de-escalation from the Vietnam War. In the Cambodian Campaign, American and South Vietnamese forces killed some 10,000 North Vietnamese/Viet Cong troops, and destroyed enemy bases and captured large quantities of weapons and supplies in underground storage bunkers. Even then, the operation was only partially successful, as most of the North Vietnamese/Viet Cong forces had earlier fled deeper into Cambodia.