In September 1964, the nationalist organization FRELIMO launched small guerilla attacks from bases in Tanzania into Cabo Delgado Province, located in northern Mozambique. FRELIMO, or the Mozambique Liberation Front (Portuguese: Frente de Libertação de Moçambique) was formed in June 1962 from the merger of three ethnic-based independence movements.

Initially, because of limited combat strength, FRELIMO planned to undertake a prolonged guerilla war instead of launching one powerful attack on Lourenço Marques, Mozambique’s capital, in the hope of quickly ousting the colonial government, as proposed by other rebel leaders. Initially, FRELIMO was handicapped by a shortage of recruits, weapons, and combat capability, and as a result, rebel operations did not seriously disrupt the government’s capacity to operate normally.

(Taken from Mozambican War of Independence – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 2)

Background During the 17th and 18th centuries, Mozambique, then known officially as the State of East Africa, served little more than as a transit stop for Portuguese and other European ships bound for Asia, as Portugal was focused on supporting its lucrative trade with India and China, and more important, developing Brazil, its prized possession in the New World.

In 1822, however, Brazil gained its independence, and with other European powers actively seeking their share of Africa during the last quarter of the 1800s, Portugal now looked to hold onto and protect its African colonies. Through an Anglo-Portuguese treaty signed in 1891, Mozambique’s borders were delineated, and by the early twentieth century, Portugal had established full administrative control over its East African colony.

Some thirty years earlier, in 1878, in order to develop Mozambique’s largely untapped northern frontier region, the Portuguese government leased out large tracts of territories to chartered corporations (mostly British), which greatly expanded the colony’s mining and agricultural industries, as well as build these industries’ associated infrastructures, such as roads, bridges, railways, and communication lines. Black Africans were used as manpower, and utilized under a repressive forced labor system – slavery had officially been outlawed in 1842, although clandestine slave trading continued until the early twentieth century. When the chartered corporations’ leases expired in 1932, the Portuguese government did not renew the contracts, and thenceforth began direct rule of Mozambique from Lisbon, Portugal’s national capital.

After World War II ended in 1945, nationalist aspirations sprung up and spread rapidly across Africa. By the 1960s, most of the continent’s colonies had become independent countries. Portugal, however, was determined to maintain its empire. In 1951, Portugal ceased to regard its African (and Asian) possessions as “colonies”, but integrated them into the motherland as “overseas provinces”. Tens of thousands of Portuguese citizens migrated to Mozambique, as well as to Angola and Portuguese Guinea under the prodding of the national government to lead the development of the new “provinces”.

Because of the immigration, racial tensions, which already were prevalent, escalated in Portugal’s African territories. Portugal took great pride in its official policy of racial inclusiveness, and upheld in its constitution the “democratic, social, and multi-racial” features of Portuguese society. However, the Portuguese Overseas Charter also recognized distinct socio-ethnic classes: citizens – European Portuguese who had full political rights; “assimilados” – black Africans who had assimilated the Portuguese way of life, could read and write, and were eligible to run for local and provincial elected office; and natives – the great majority of black Africans who retained their traditional ways of life.

The Portuguese monopolized the political and economic systems of the colony, while the general population had limited access to education and upward social and economic mobility. By the early 1960s, less than 1% of black Africans had attained “assimilado” status. The colonial government repressed political dissent, forcing many Mozambican nationalists into exile abroad, and used PIDE (Policia Internacional e de Defesa do Estado), Portugal’s security service, to turn Mozambique into a police state.

In June 1962, exiled Mozambican nationalists met in Dar es Salaam, Tanganyika, and merged three ethnic-based independence movements into one nationalist organization, FRELIMO or Mozambique Liberation Front (Portuguese: Frente de Libertação de Moçambique). Led by Eduardo Mondlane, FRELIMO initially sought to gain Mozambique’s independence by negotiating with the Portuguese government. FRELIMO regarded the Portuguese as foreigners who were exploiting Mozambique’s human and natural resources, and were unconcerned with the development and well-being of the indigenous black population.

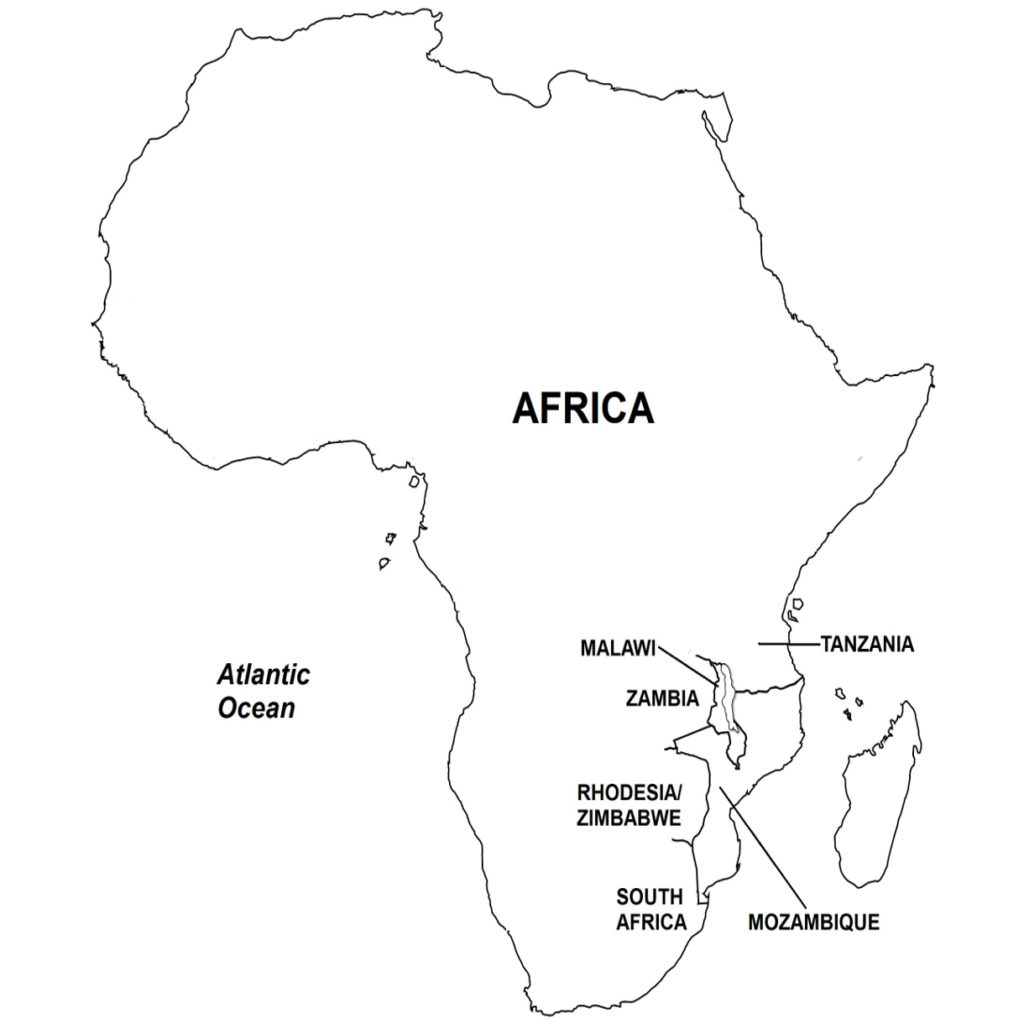

By 1964, Portugal’s intransigence and the Mozambican colonial government’s repressive acts, including the so-called Mueda Massacre, where security forces opened fire on a crowd of demonstrators, had radicalized FRELIMO into believing that Mozambique’s independence could only be gained through armed struggle. Further motivating FRELIMO into starting a revolution was that Mozambique’s neighbors recently had achieved their independences, i.e. Tanzania in 1961, and Malawi and Zambia in 1964, and these countries’ black-ruled governments would be expected to support Mozambique’s struggle for independence as well.