The Indonesia-Malaysia Confrontation, or Konfrontasi, began on April 12, 1963, when two groups of Indonesian-supported Sarawak rebels crossed the border from Nangabadan, Kalimantan into Sarawak and one group attacked a police station in Tebedu and the other raided a border village in western Sarawak. Indonesia-based infiltrations to Sarawak and Sabah (the latter renamed from North Borneo) involved platoon-size units carrying light weapons which launched hit-and-run attacks on enemy targets and armed raids as well as carried out propaganda campaigns in settlements and villages. By 1964, the Indonesian Army became directly involved in the fighting. At their peak, some 22,000 Indonesian troops and 4,000 irregulars, and 2,000 Sarawak rebels participated in Konfrontasi. On the Malaysian side, the British Army, which included Gurkhas (Nepali soldiers in the British Army), and Malaysian troops, and later Australian and New Zealand contingents, formed the defensive forces, whose operations consisted of confronting and repelling the attacks.

(Taken from Indonesia-Malaysia Confrontation – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 4)

Despite being a low-intensity conflict, Konfrontasi took place in extremely difficult conditions, as the 1,000-mile frontier (and much of the island) between Kalimantan and Malaysian Borneo was deep jungle mountains covered with thick forest cover and dense vegetation with seasonal heavy rainfalls, and intersected by many rivers, these natural barriers greatly reducing troop movements. No roads or plotted trails existed and British contemporary maps provided only scant topographic details; maps used by the Indonesian Army were even much less reliable.

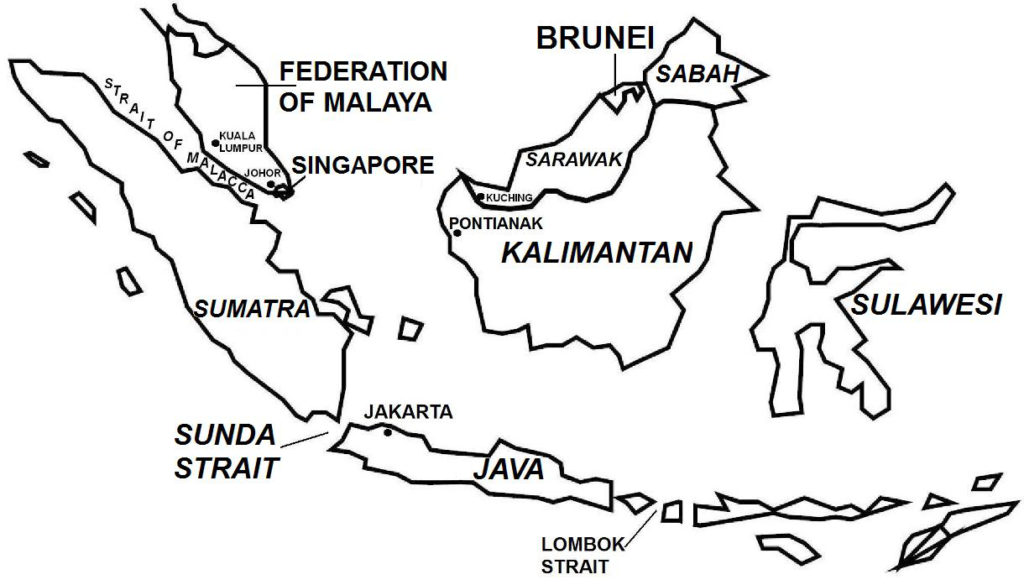

Figure 35. Some key areas during Konfrontasi or Indonesia-Malaysia Confrontation.

In February 1964, representatives from Indonesia and Malaysia

held peace talks in Bangkok, Thailand, which were followed in July by more

negotiations in Tokyo, Japan; however, these meetings

failed to produce a settlement. The

second half of 1964 marked the most intense phase of the war starting in July

when the Indonesian Army, by now carrying out or leading most of the

cross-border infiltrations, launched 13 border incursions and 34 other

incidents inside Malaysian Borneo.

Then on August 14, 1964, the day President Sukarno gave his “Year of Living Dangerously” speech during Indonesian Independence Day celebrations in Jakarta, the conflict expanded into Peninsular Malaysia when the Indonesian armed forces sent 100 commandos, supported by a team of Malaysian communists, who made a seaborne crossing over the Malacca Strait from Sumatra and landed south of Johor. British and Malaysian forces contained the intrusion, which ostensibly was aimed at establishing rebel bases on the mainland with the ultimate goal of inciting a general uprising to overthrow the Malaysian government and install a socialist regime. Then two weeks later, on September 2, 1964, Indonesian Air Force transport planes airdropped 96 paratroopers in Labis, near Johor; this attack also was stopped, with most of the paratroopers killed or captured.

The British government was so alarmed by the attacks on the Malayan mainland that it resolved to carry out a show of force to deter further intrusions. In September 1964, in the incident known as the Sunda Strait Crisis, the British Navy sent a squadron of ships that included the aircraft carrier HMS Victorious on a voyage from Singapore to Fremantle, Western Australia, and which was to pass via the Sunda Strait, located between Sumatra and Java. Invoking international law that granted the right of innocent passage through Indonesian waters, the British government requested permission from Indonesia, which produced a flurry of increasingly confrontational diplomatic exchanges between the two countries. The Indonesian government then stated that its navy would be carrying out naval exercises in the Sunda Strait and that the British flotilla, which it deemed offensive in nature because of the presence of the aircraft carrier, posed a threat whose consequences would be hard to predict if the ships entered the Strait. A tense three-week impasse followed, but after further strenuous negotiations, the British ships were allowed to pass through Indonesian waters but via the Lombok Strait, located east of Java, averting what could have led into an unforeseen war between Britain and Indonesia; the incident was the most intense, dramatic phase of Konfrontasi. Britain possessed overwhelming military superiority against Indonesia, but its role as a former colonial subjugator of peoples would embroil it a political and diplomatic nightmare in case of a war against a Third World nation, more so against Indonesia that had gained its independence through an armed struggle against another colonial power.

In July 1964, the British government approved Operation Claret, a clandestine counter-offensive to be launched into Kalimantan aimed at pre-empting the Indonesian Army’s cross-border infiltrations. Aware that such operations might generate a negative diplomatic backlash from the international community, Britain planned and executed Claret under top-secret security and restraint, and acknowledged its existence only in 1974, or a decade after the war. Claret also involved the participation of Australia and New Zealand, whose Special Forces together with those of the British, carried out infiltration operations into Kalimantan to seek out and locate Indonesian forces that were about to launch cross-border attacks into Malaysian Borneo. With the enemy positions pinpointed, regular British and Malaysian combat forces then were sent to contain these Indonesian units before the latter could launch their attacks. The air transport superiority of the British military, particularly the use of helicopters to move the Special Forces forward and deep inside Indonesian territory, was crucial to Claret’s success. The British military also used jungle combat experience it had gained in the Malayan Emergency (a failed uprising by the Malayan Communist Party in the Malay Peninsula during 1948-1960), further refining its jungle fighting tactics that forced the Indonesian Army to a defensive stance, particularly since the British eventually carried out penetration operations with virtual impunity and at increasingly greater depth inside Kalimantan. Operation Claret’s effective intelligence gathering intrusions and control of the jungle as well as the British emphases on speed and flexibility in carrying out hit-and-run attacks proved successful in what the British planners called “aggressive defense”, inflicting heavy casualties on the enemy and forcing the Indonesian Army to stop further intrusions into Malaysian Borneo.

In December 1964, President Sukarno renounced Indonesia’s membership in the UN in protest of the international body’s electing Malaysia as a non-permanent member of the United Nations Security Council (UNSC). Also, British combat successes led to increased tensions between President Sukarno and the Indonesian military high command, relations which already were strained because of the military’s mistrust of the communist PKI which President Sukarno viewed as a counterweight against the power of the military establishment. Furthermore, by 1965, President Sukarno had lost much of his once formidable popular support in Indonesia because of the country’s ongoing acute economic crisis brought about by uncontrolled inflation, widespread poverty and unemployment, high foreign debt, and neglected infrastructures and development. Indonesia’s internal problems ultimately would force an end to the war.