On March 31, 1968, U.S. President Lyndon B. Johnson delivered the speech, “Steps to Limit the War in Vietnam”, in a television address to the nation. At the end of his speech, he announced, “I shall not seek, and I will not accept, the nomination of my party for another term as your President.” The address came shortly after the end of the Tet Offensive by North Vietnam and the Viet Cong during the Vietnam War.

The Tet Offensive fatally damaged President Johnson’s political career. Opposition within the president’s own Democratic Party came at a crucial time, as the presidential election was scheduled later that year, in November 1968. Following a lackluster performance in the New Hampshire primary, President Johnson, in a nationwide broadcast, announced that he would not seek re-election as president. In the same broadcast, he suspended U.S. bombing of North Vietnam in all areas north of the 19th parallel as an incentive to North Vietnam to start peace talks. The North Vietnamese government responded positively, and in May 1968, peace talks opened in Paris. Because the talks made little progress, on November 1, 1968, on President Johnson’s orders, aerial bombing of all North Vietnam was stopped (ending the 3½-year-long bombing campaign of Operation Rolling Thunder).

(Taken from Vietnam War – Wars of the 20th Century – Twenty Wars in Asia: Vol 5)

In May and August 1968, the Viet Cong launched smaller “Mini-Tet” attacks as part of its ongoing “General Offensive, General Uprising” campaign. South Vietnamese and American forces, now being more vigilant, parried these attacks. Also in the immediate aftermath of the first Tet Offensive, the Viet Cong/NLF initially gained control of the rural areas which South Vietnamese forces had evacuated to defend the cities and towns. But in the post-Tet period, American and South Vietnamese large-scale search and destroy operations regained control of the countryside.

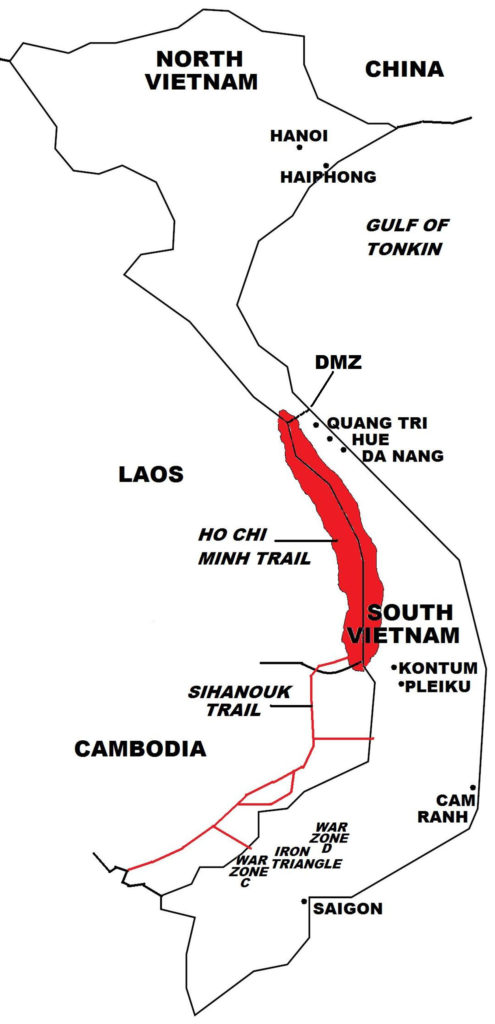

Ultimately, the Tet Offensive was a military disaster for the Viet Cong/NLF, as its military units were expelled from South Vietnam and forced into hiding in the Cambodian border regions. As a result, the Viet Cong experienced desertions, low morale, and difficulty to recruit new fighters. The Viet Cong soon ceased to be a native southern insurgency, as its ranks increasingly became filled by North Vietnamese cadres. In the end, the Viet Cong came under full control of North Vietnam.

For the United States, the Tet Offensive was a decisive military victory, but one that soon turned into a moral defeat for the American people, and a political disaster for President Johnson. During the early years of the war, President Johnson had issued only carefully measured amounts of information to the American public regarding the true military situation in Vietnam. He continued to declare that U.S. war strategy in Vietnam remained the same, despite the fact that American military involvement in the war was deepening and more and more troops were being sent to Vietnam. Soon, the American mass media detected a “credibility gap” between the U.S. government official pronouncements and the reports coming from Vietnam. In 1966, the first signs of American public opposition became evident, which by 1967, grew into a more vocal and radical protest movement.

Initially, President Johnson’s increased involvement in Vietnam enjoyed overwhelming political support, as evidenced by the near unanimous passage of the 1964 Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, as well as the high popular support. Opinion polls at the time showed that 80% of Americans supported the war. But by 1967, surveys were showing growing opposition to the war. To counter falling public support, and media reports that the war had reached a stalemate, in the fall of 1967, the Johnson administration embarked on a high-profile propaganda campaign stating that the war was being won. Government officials, including Vice-President Hubert Humphrey and the American ambassador to South Vietnam, issued glowing statements in support of the war. High-ranking military officers also released data showing that the enemy was suffering from high numbers of its soldiers killed, weapons lost, and bases and camps captured. General Westmoreland also announced that the U.S. military had “reached an important point when the end begins to come into view”, implying that American victory was imminent.

However, President Johnson’s attempts to win back public support through propaganda backfired, as the Tet Offensive showed that not only was the Viet Cong far from being defeated, it had the strength to launch a full-scale offensive across South Vietnam. As a result, support for the anti-war movement in the United States increased dramatically. Hundreds of thousands of people participated in protest marches and rallies. These demonstrations sometimes deteriorated into violent confrontations with security forces. Anti-war sentiment particularly was strong among college students, and universities and colleges became centers of unrest. Active involvement came from many sectors, including women’s movements, social rights groups, African-Americans, and even Vietnam War veterans.

Tet also fatally damaged President Johnson’s political career. Opposition within the president’s own Democratic Party came at a crucial time, as the presidential election was scheduled later that year, in November 1968. Following a lackluster performance in the New Hampshire primary, President Johnson, in a nationwide broadcast, announced that he would not seek re-election as president. In the same broadcast, he suspended U.S. bombing of North Vietnam in all areas north of the 19th parallel as an incentive to North Vietnam to start peace talks. The North Vietnamese government responded positively, and in May 1968, peace talks opened in Paris. Because the talks made little progress, on November 1, 1968, on President Johnson’s orders, aerial bombing of all North Vietnam was stopped (ending the 3½-year-long bombing campaign of Operation Rolling Thunder).

Also in 1968, because of domestic pressures, the Johnson administration implemented a major shift in American involvement in the war: henceforth, the U.S. military would gradually disengage from the Vietnam War, and after a period of being built up, the South Vietnamese military would take over the fighting (the process known as the “Vietnamization” of the war). The South Vietnamese military buildup was meant to balance out the phased reduction of U.S. ground forces. U.S. forces in Vietnam, which peaked in 1968 at 530,000 troops, would see a steady reduction in succeeding years: 1969 – 475,000; 1970 – 335,000; 1971-156,000; 1972 – 24,000; and 1973 – 50. More than these numbers alone, the pull-out of American troops would have a decisive impact on the outcome of the war.

In June 1968, General Creighton Abrams, who succeeded as over-all commander of U.S. forces in Vietnam (MACV), gradually shifted U.S. combat strategy away from search and destroy missions to “clear and hold” (i.e. to clear the insurgents from an area, which would then be held) operations, and implemented a moderately successful “hearts and minds” campaign (under a newly formed agency, the Civil Operations and Revolutionary Development Support, CORDS) to gain the sympathy of the civilian population for the South Vietnamese government.

In 1969, newly elected U.S. president, Richard Nixon, who took office in January of that year, continued with the previous government’s policy of American disengagement and phased troop withdrawal from Vietnam, while simultaneously expanding Vietnamization, with U.S. military advice and material support. He also was determined to achieve his election campaign promise of securing a peace settlement with North Vietnam under the Paris peace talks, ironically through the use of force, if North Vietnam refused to negotiate.

In February 1969, the Viet Cong again launched a large-scale Tet-like coordinated offensive across South Vietnam, attacking villages, towns, and cities, and American bases. Two weeks later, the Viet Cong launched another offensive. Because of these attacks, in March 1968, on President Nixon’s orders, U.S. planes, including B-52 bombers, attacked Viet Cong/North Vietnamese bases in eastern Cambodia (along the Ho Chi Minh Trail). This bombing campaign, codenamed Operation Menu, lasted 14 months (until May 1970), and segued into Operation Freedom Deal (May 1970-August 1973), with the latter targeting a wider insurgent-held territory in eastern Cambodia.