On April 15, 1998, Pol Pot, former Prime Minister of Democratic Kampuchea from 1976 to 1979 passed away in Anlong Veng near the Thai-Cambodian border. He was the leader of the Khmer Rouge (Kampuchean Communist Party) and ruled Kampuchea over a Marxist-Leninist government. He transformed the nation into an agrarian society, with the entire population forced to relocate in the countryside and work on collective farms. Extremely dire conditions on these farms which included arduous living and working conditions, restricted food intake and poor medical care, worsened by mass killings, brought about the Cambodian Genocide, where some 1.5 to 3 million people, about 25% of the population, perished.

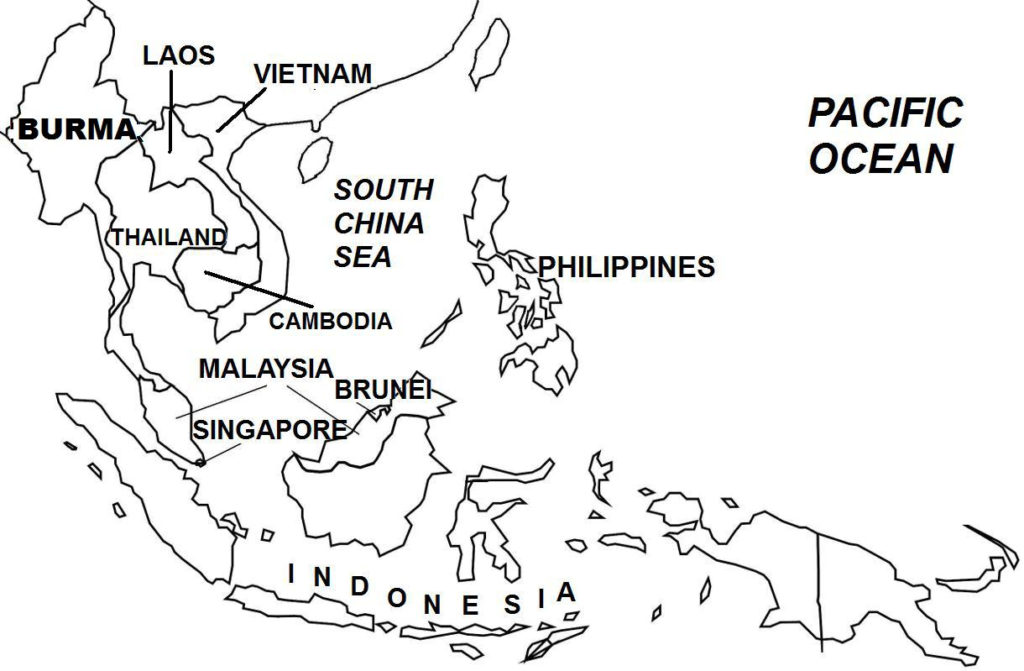

In December 1978, Vietnam invaded Cambodia, overthrowing Pol Pot, who fled to the jungles near the Thai-Cambodian border and waged a guerrilla war against the Vietnamese who occupied the country and installed a new communist government in Phnom Penh.

(Taken from Cambodian Genocide – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 5)

On April 17, 1975, the Khmer Rouge, a Cambodian communist rebel group, emerged victorious in the Cambodian Civil War (previous article) when its forces captured Phnom Penh, overthrew the United States-backed government of the Khmer Republic, and took over the reins of power. In January 1976, the Khmer Rouge ratified a new constitution, which changed the country’s name to “Democratic Kampuchea” (DK). In the Western press, DK, as well as the new Cambodian government, continued to be referred to unofficially as “Khmer Rouge”.

In April 1976, the Khmer Rouge’s newly formed legislature, called the Kampuchean People’s Representative Assembly, elected the country’s new government with Pol Pot (whose birth name was Saloth Sar) appointed as Prime Minister. In September 1976, Pol Pot declared that his government was Marxist-Leninist in ideology that was closely allied with Chairman Mao Zedong’s Chinese Communist Party. The following year, September 1977, he revealed the existence of Kampuchea’s state party called the Kampuchean Communist Party, also stating that it had been formed 17 years earlier, in September 1960. These disclosures confirmed the long-held belief by international observers that the Khmer Rouge was a communist organization, and that DK was a one-party totalitarian state.

Pol Pot had long held absolute power in the Khmer Rouge and (secretly) held the position of General Secretary of the party since 1963 behind the façade of a front organization called Angkar Padevat (“Revolutionary Organization”, usually shortened to Angkar, meaning “Organization”). Ostensibly, Angkar was politically moderate, as its leaders were former high-ranking Cambodian government officials who held only moderate leftist/socialist beliefs. However, behind the scenes, hard-line communist party ideologues controlled the movement.

During the Cambodian Civil War, the Khmer Rouge operated behind the cover of Prince Norodom Sihanouk, the deposed Cambodian ruler who was widely popular among the Cambodian masses, through a political-military alliance called the Royal Government of the National Union of Kampuchea, or GRUNK (French: Gouvernement royal d’union nationale du Kampuchéa). GRUNK supposedly was a coalition of all opposition movements, and was nominally controlled by Sihanouk as its head of state. When the Khmer Rouge seized power in April 1975, Sihanouk continued to hold the position of head of state under the new Khmer Rouge regime, but held no real political power. In April 1976, after resigning as head of state, he was placed under house arrest.

In foreign relations, DK isolated itself from much of the international community. Shortly after coming to power, the remaining 800 foreign nationals in Cambodia were gathered at the French Embassy in the capital, and then trucked out of the country through the Thai border. All foreign diplomatic missions in Kampuchea were closed down. However, when the DK government later was granted a seat at the United Nations (UN) to represent Kampuchea (Cambodia’s new name), a small number of foreign embassies were allowed to reopen in Phnom Penh. But as foreign travel to Kampuchea was severely restricted, the country was virtually cut off from the outside world. As a result, apart from official government pronouncements, practically nothing was known in the outside world about the true conditions in the country during the Khmer Rouge regime.

At the core of the Khmer Rouge’s Marxist ideology was the regime’s desire to achieve the purest form of communism, that of a classless society. The Khmer Rouge also advocated ultra-nationalism and anti-imperialism, and desired to eliminate foreign control and achieve national self-sufficiency, first through the phased, collectivized agricultural development of the countryside. Before coming to power, the Khmer Rouge had rejected the advice of Chinese communist leaders who told them that the process of transition from socialism to communism should not be rushed. But the Khmer Rouge, particularly its leader Pol Pot, was determined to achieve communism rapidly without the transitional phases of socialism.

The Khmer Rouge first implemented its concept of communism sometime in 1970 at Ratanakiri Province in the northeast, where it forced the local population to move from villages to agrarian communes. The Khmer Rouge also carried out other forced relocations at Steung Treng, Kratie, Banam and Udong. In 1973, the Khmer Rouge concluded that the “final solution” to end capitalism in Cambodia was to empty all the towns and cities, and move all Cambodians to the rural areas. Simultaneously, in areas under its control, the Khmer Rouge executed teachers, local leaders, traders, and other “counter-revolutionaries”. As well, all forms of dissent or opposition were met with brutal reprisals. By 1974, the Khmer Rouge was carrying out indiscriminate killings of men, women, and children. The rebels also destroyed villages, such as those that occurred in Odongk and Ang Snuol districts, Sar Sarsdam village, and other areas.

The Cambodian government soon received reports of these brutalities being committed by the Khmer Rouge, but ignored them. An invaluable insight into the workings of the Khmer Rouge came in 1973 (two years before the rebels came to power) when a former school teacher, Ith Sarin, went to the northwest and central regions and joined the Khmer Rouge. Eventually, Ith Sarin become disillusioned and left, and returned to the fold of the law. His work, Regrets for the Khmer Soul (Khmer: Sranaoh Pralung Khmer), revealed that the Khmer Rouge was a Marxist organization that operated behind a front movement called “Angkar”. Angkar had a well-structured organization that imposed brutal, repressive policies in controlled areas, which it called “liberated zones”.

The Cambodian government banned Ith Sarin’s book and jailed its author for being a communist sympathizer. Then, a report by an American diplomatic officer, Kenneth Quinn, which described Khmer Rouge atrocities in eastern and southern Cambodia, was also ignored, this time by U.S. authorities. Contemporary news reports by some American newspapers (e.g. The New York Times, Baltimore Sun), which described the Khmer Rouge carrying out massacres, executions, and forced evacuations, also escaped scrutiny by the U.S. government.

On April 17, 1975, a few hours after capturing Phnom Penh, the Khmer Rouge ordered all residents to leave their homes and move to the countryside. The order to leave was both urgent and mandatory – those who resisted would be (and were) killed. There were no exceptions, and even the sick and elderly were ordered to leave. Hospitals were closed down and the patients, regardless of their medical conditions, were evacuated, some still in their beds and attached to intravenous tubes.

Within a few days, Phnom Penh was completely depopulated, with all its residents – some 2.5 million (30% of the country’s population) and ordered to take only a few belongings – making their way in long convoys in ox carts, motorbikes, scooters, and bicycles, but mostly on foot, to rural areas across the country. The Khmer Rouge’s order was for all persons to return to their ancestral villages.

In later testimonies, genocide survivors said of being told by Khmer Rouge cadres that the evacuation was being undertaken because American planes were about to bomb the city, or that the Khmer Rouge was conducting operations to flush out remaining government soldiers hiding in the city, or that U.S. Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) agents were planning to launch subversive actions in Phnom Penh to undermine the revolution, etc. Other survivors said of being told that their destination was only “two or three kilometers away” and that they could return “in two or three days”.

The Khmer Rouge, in official pronouncements at the time and after the genocide, said that the forced evacuation of Phnom Penh was necessary because of an imminent food shortage and the danger of starvation to city residents, and that the Khmer Rouge did not have the logistical capability to fill the void left by the American departure. (In the final stages of the war, the U.S. military was supplying Phnom Penh with food supplies through the Mekong River and later by airlifts.) Furthermore, the Khmer Rouge leadership stated that the presence of large numbers of people in the rural areas would force the former urban residents to grow their own food (thus averting a food shortage), and also help in the reconstruction of the war-ravaged countryside.

The decision to depopulate Phnom Penh was made sometime in February 1975 (three months before the city’s capture), which was part of the Khmer Rouge’s plan of turning the country into a single collectivized agriculture-based socialist state worked by peasant-farmers in a classless society. The Khmer Rouge drew its inspiration from the ancient Khmer Empire (A.D. 800-1400), whose wealth and power came from its vast agricultural estates. The Khmer Rouge sought to duplicate this past greatness, but under the principles of Marxism-Leninism and ultra-nationalism.

The Khmer Rouge viewed the Cambodian countryside as the means to achieve pure communism, self-sufficiency, and isolation from foreign influences. During the Cambodian Civil War, the Khmer Rouge owed much of its success to the rural areas, where it had established its first permanent bases, and from where it relied on rural support for its food, information, recruits, and sanctuaries. By contrast, the Khmer Rouge did not obtain any support from large urban areas, which it viewed as decadent, West- and capitalism-corrupted, and must be eliminated, as they served no purpose for the transformation of the country into a communist state.

Within a few months after the Khmer Rouge completed the mass transfer of the Cambodian population to the countryside, Phnom Penh was partially repopulated, but only by the Khmer Rouge central government and its associated security units. During the DK period, Phnom Penh’s population probably reached 40,000 – 100,000 people.

In September 1975 through 1976 and 1977, the Khmer Rouge carried out other forced depopulations in other regions across Kampuchea, particularly in the newly designated Central, Southwest, Western, and Eastern Zones, (present-day provinces of Takeo, Kampong Cham, Kampong Chhnang, Kampong Speu, Kampong Thom, and Kandal) the Siem Reap and Preah Vihear Sectors, Northwest Zone (present-day provinces of Banteay Meanchey, Battambang, and Pursat), and Central (Old North) Zone (Kampong Cham and Kampong Thom).

The Khmer Rouge classified the general population into two groups: “Old People” (also called base people or full-rights people) and “New People” (also called April 17 people or dépositees). The “Old People” were the peasants, villagers, and essentially those who had supported the Khmer Rouge during the civil war, and were deemed essential to the nation’s communist transformation. Also designated as Old People were Kampuchean Communist Party cadres, government officials, and military personnel. The “New People” were the evacuated residents of the cities and towns, including the civilian and military components of the previous regime, and essentially those who had opposed the Khmer Rouge during the war, and who were deemed non-essential to the socialist revolution, and thus were expendable.

During the civil war, the Khmer Rouge prepared a list of high-ranking civilian and military officials targeted for execution. Instead, after the war, the Khmer Rouge arrested and executed all captured government officials, military officers, businessmen, academics and intellectuals, teachers, and anyone who had played even only a moderate role in or were identified with the former regime. Perhaps the worst mass killing committed at this time was the Tuol Po Chrey Massacre, where some 3,000 (to as many as 10,000) mostly military officers, including the provincial governor and government officials, were executed in a single day in Tuol Po Chrey, Pursat Province. As a result, professional people, including doctors and engineers, technicians, and anyone who possessed some education or skilled training, did not reveal their backgrounds and pretended as belonging to the common people. Even then, the Khmer Rouge arrested and killed those who wore eyeglasses, spoke French or other foreign languages, or anyone it considered to be an intellectual, or had been part of the former regime, or displayed some Western influence.

On arriving at their destinations, the New People were organized into brigades to begin work in agrarian communes. Collectivized farming was the cornerstone of the Khmer Rouge regime, and communal farms were set up across the country, consisting of separate Old People and New People communes. The Khmer Rouge called the start of its social revolution “Year Zero”, when it planned to wipe out everything that had come before, and establish a new Kampuchean state that would achieve greatness equal to that of the ancient Khmer Empire.

The communal farms that were set up were slave labor camps, where people worked everyday from dawn to dusk (sometimes up to 10 or 11 at night) doing farm work such as growing crops, clearing forests, draining swamps, digging irrigation ditches, and building dams. There were no rest days, and all work was done by hand or using basic tools (but no machineries). Rest breaks and meals were restricted and inadequate, and work quotas and regulations were strictly enforced. Exhaustion and illness were deemed equivalent to laziness, while complaining about the work or foraging for root crops, vegetables, or fruit in the forest or wayside for personal consumption were subject to severe punishment. Taking anything from the ground or water was considered stealing from the state. These rules were administered by armed youths, some as young as twelve years old.

Men and women were segregated into separate living and dining quarters, and marital relations were restricted to specified schedules. Social life was eliminated, with religious holidays, celebrations, music, and dance forbidden, as were courtship and family life. Private ownership was prohibited – the fields, farmlands, crops, and all items in the communes, even the clothes and utensils a person used, were state property.

Workers were subjected to revolutionary teachings. The government, which was identified only as “Angkar” (organization), was described as the all-powerful, all-knowing, and benevolent entity that worked only for the common good. Unknown and unseen, Angkar was feared by all. Indeed, the highest ranking leaders of the Khmer Rouge regime, referred to as Angkar Loeu (“Upper Organization”), were hardly known or rarely seen by the general population. A worker who violated any regulation was given a warning. Three warnings automatically led to an “invitation” by Angkar, which meant death by execution. Executions were usually carried out at nightfall in a wooded area just outside the commune.

The Khmer Rouge considered children as indispensable to the socialist revolution, and thus housed them collectively and separately from their parents, and indoctrinated them into communist teachings. Children also were trained to reject their parents and families, to submit to Angkar, and to hate their enemies. Children were made to feel no sympathy or emotions, and were trained to kill animals in violent ways.

The Khmer Rouge particularly targeted the “New People” who, having lived in the towns and cities, were unprepared for agrarian work and lifestyle. As well, the regime’s harshest policies were directed at them. In the first year, the “New People” population declined considerably as a result of overwork, sickness and disease, summary executions, and starvation. The Khmer Rouge also took away most of the harvest, which left the New People communes with insufficient food supplies.

“Old People” communes generally were treated much better. However, in post-war testimonies, survivors from “Old People” communes have stated that they were subject to the same harsh, repressive conditions experienced by the “New People”.

The Khmer Rouge applied radical measures to speed up the country’s transition to communism. Banks were closed down; money was abolished. Industries were dismantled as government focused on agricultural production. A few industries, e.g. rubber-processing plants, were later reopened, but placed under strict state control. Schools also were closed down, and teachers were executed. The Khmer Rouge later opened a number of schools that taught only revolutionary ideology, and only the children of the “Old People” class were allowed to study in them.

Hospitals also were closed down, and most doctors were executed. The Khmer Rouge viewed modern medicine as “counter-revolutionary” and anathema to communist ideology. As a result of the absence of proper medical care, most of the general population suffered from sicknesses and diseases. About 80% of the people contracted malaria. Only traditional forms of medicine were allowed, which proved ineffective, particularly for more serious illnesses. The government did reopen some hospitals which practiced modern medicine, but these medical facilities serviced only government officials, the military, party cadres, and their families.

The practice of religion, although guaranteed by the Khmer Rouge constitution, was suppressed. Thousands of Buddhist monks (Buddhism was the country’s predominant religion) were executed or forced to become farm workers, Buddhist images were destroyed, and temples and pagodas were turned into prisons, execution sites, or pig pens. Other religions were persecuted as well. The ethnic minority Chams, who were Muslims, were forced from their homeland and dispersed among the agrarian communes in other regions. As well, they were killed in large numbers in massacres, and their mosques were used to raise pigs. The country’s small Roman Catholic population also was forced into slave labor, and the Notre Dame Cathedral and other churches in the capital were destroyed. To end all knowledge of and ties to the past, the Khmer Rouge destroyed libraries and burned books.

The Khmer Rouge, with its vision of achieving Khmer racial purity, targeted other ethnicities, including Chams, Laotians, Chinese, and particularly the Vietnamese, who were blamed for all the country’s past and present troubles. Nearly all the remaining 200,000 ethnic Vietnamese were expelled from the country within a few months after the Khmer Rouge came to power, following an earlier expulsion of 300,000 by the previous regime. Other ethnic minorities were subject to persecutions that resulted in high numbers of deaths, forcing thousands of others to flee the country.

During the Cambodian Civil War, the Khmer Rouge functioned as a coalition of different regional guerilla militias, with each militia operating as a virtually autonomous unit under the nominal control of the KCP Central Committee headed by Pol Pot. After achieving victory in the war, these regional forces took control of the administrative and military functions in their respective regions. Although Saloth Sar (now going by his nom-de-guerre Pol Pot) and his deputies were recognized as the national leaders of the new state, the various regional administrations continued to exercise broad autonomous powers in their areas and outside the control of the Phnom Penh central government. Two (failed) coup attempts against the central government – in July and September 1975 – highlighted the political instability during this time. This period also coincided with the social upheavals generated by the population transfers, when just after the war (April 1975) and then in late 1975 until 1976, the Khmer Rouge executed thousands of “enemies of the state” and “counter-revolutionaries” who were identified with the previous regime.

Then in 1977, Pol Pot was ready to launch a purge of the party. After Pol Pot entered into an alliance with Southwest Zone leader Ta Mok, their combined forces initiated a series of purges in the Eastern, Northern, and Western zones in February 1977, and in the Northwest zone in May. The purges were most intense in the Eastern Zone, where some 100,000 local cadres, whom Pol Pot believed were traitors and in alliance with the Vietnamese government in Hanoi, were killed in massacres. Pol Pot had derisively called Eastern Zone cadres as having “Khmer bodies with Vietnamese minds”.

Suspected disloyal cadres were sent to “interrogation and detention centers”, which really were torture and execution facilities. These institutions originally were established to prosecute “counter-revolutionaries” (i.e. persons identified with the previous regime), but soon became packed with arrested communist cadres as the purges intensified. Some 150 such facilities existed, which included Security Prison 21 (S-21) at Tuol Sleng, Phnom Penh, where many civilian and military cadres, including those with high-ranking positions, were imprisoned, tortured, and executed. Various forms of tortures were employed which were so brutal and painful that the prisoners confessed to committing nonsensical crimes which government authorities had prepared beforehand. In many cases, prisoners were forced to implicate members of their own family, who then were arrested and subjected to the same tortures. After a period of detention, the prisoners were taken to another location, where they were executed and buried in mass graves. To save on ammunition, Khmer Rouge executioners rarely shot their prisoners. Instead, the executions were carried out using a pickaxe, iron bar, or wooden club, which were struck on prisoners’ head, killing them. Children were executed first by grasping them by their legs and then bashing their heads onto a tree trunk.

The Khmer Rouge killed a large number of Cambodians into what tantamounts to genocide. Various estimates place the total deaths of the Cambodian Genocide at 1½ – 2½ million people, to even as high as 3 million, with about half of the fatalities caused by executions, and the rest due to overwork, starvation, sickness, and diseases. Another 300,000 perished from starvation in the immediate aftermath of the genocide (in the period after January 1979). Starting in the 1990s, some 20,000 mass graves have been unearthed containing the skeletal remains of some 1.4 million executed prisoners. These mass graves are known also as the killing fields, that is, they were the execution sites used by the Khmer Rouge.

After two decades of war, in late 1991, peace was restored in Cambodia. In 1997, the Cambodian government began efforts to investigate the mass killings that occurred during the Khmer Rouge era. In June 2003, Cambodia and the United Nations established the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia (ECCC; informally known as the Khmer Rouge Tribunal) to prosecute high-ranking Khmer Rouge leaders for various crimes including genocide, war crimes, and crimes against humanity. The start of the trails was delayed because of the lack of government funds. But with financial support provided by foreign countries, the ECCC started the judicial processes in 2006. A number of top Khmer Rouge officials (i.e. Nuon Chea, the second-highest leader; Khieu Samphan, Khmer Rouge head of state; and Kang Kek Iew (“Comrade Duch”), head of internal security and S-21 commandant) have since been found guilty of criminal acts. Pol Pot had earlier passed away in April 1998, and thus was not tried.

The Cambodian Genocide ended in early January 1979, with the overthrow of the Khmer Rouge government following the Vietnamese Army’s invasion of Cambodia.