An escalation of hostilities, including artillery exchanges and air attacks, took place in the period preceding the outbreak of war. On September 22, 1980, Iraq opened a full-scale offensive into Iran with its air force launching strikes on ten key Iranian airbases, a move aimed at duplicating Israel’s devastating and decisive air attacks at the start of the Six-Day War in 1967. However, the Iraqi air attacks failed to destroy the Iranian air force on the ground as intended, as Iranian planes were protected by reinforced hangars. In response, Iranian planes took to the air and carried out retaliatory attacks on Iraq’s vital military and public infrastructures.

Throughout the war, the two sides launched many air attacks on the other’s economic infrastructures, in particular oil refineries and depots, as well as oil transport facilities and systems, in an attempt to destroy the other side’s economic capacity. Both Iran and Iraq were totally dependent on their oil industries, which constituted their main source of revenues. The oil infrastructures were nearly totally destroyed by the end of the war, leading to the near collapse of both countries’ economies. Iraq was much more vulnerable, because of its limited outlet to the sea via the Persian Gulf, which served as its only maritime oil export route.

(Taken from Iran-Iraq War – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 4)

Background In January 1979, anti-royalist elements (Islamists, nationalists, liberals, communists, etc.) in Iran forced the reigning Shah (king) Mohammad Reza Pahlavi to leave for exile abroad, and this event, known as the Iranian Revolution, effectively ended Iran’s monarchy. The following month, February 1979, Ayatollah (Shiite Muslim religious leader) Ruhollah Khomeini, the inspirational and spiritual leader of the revolution, returned from exile in France and set up a provisional government led by Prime Minister Mehdi Bazargan. After a brief period of armed resistance put up by royalist supporters, the revolution prevailed and Ayatollah Khomeini consolidated political power.

Then in a national referendum held in March 1979, Iranians overwhelmingly voted to abolish the monarchy (ending 2,500 years of monarchical rule) and allow the formation of an Islamic government. Then in November 1979, the Iranian people, in another referendum, adopted a new constitution that turned the country into an Islamic republic and raised Ayatollah Khomeini to the position of Iran’s Supreme Leader, i.e. head of state and the government’s highest ranking political, military, and religious authority. Prime Minister Bazargan, whose liberal democratic and moderate government had held only little power, resigned in November 1979. By February 1980, Iran had fully transitioned to a theocracy under Ayatollah Khomeini, with executive functions run by a subordinate civilian government led by President Abolhassan Banisadr.

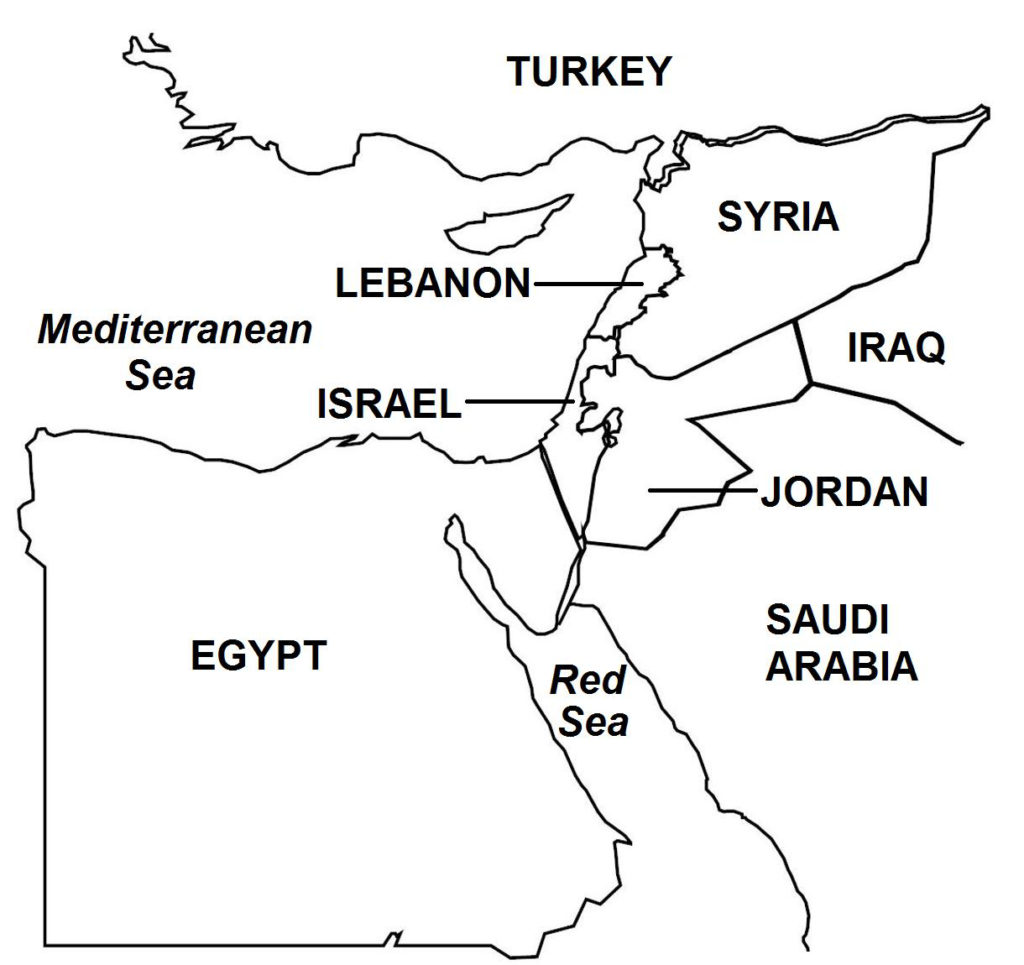

The political unrest in Iran had been watched closely by Iraq, Iran’s neighbor to the west, and particularly by Saddam Hussein, the Iraqi dictator. In the period following the Iranian Revolution, relations between the two countries appeared normal, with Iraq even offering an invitation to new Iranian Prime Minister Bazargan to visit Iraq. But with Iran’s transition to a hard-line theocratic regime, relations between the two countries deteriorated, as Iran’s Islamist fundamentalism contrasted sharply with Iraq’s secular, socialist, Arab nationalist agenda.

This breakdown in relations was only the latest in a long history of Arab-Persian hostility that resulted from a complex combination of ethnic, sectarian, political, and territorial factors. During the period when the Ottoman Empire ruled over the Middle East (16th – 19th centuries, to early 20th century), the Ottoman Empire and Persian Empire fought for possession of sections of Mesopotamia, (present-day Iraq), including the Shatt el-Arab, the 200-kilometer long river that separates present-day southern Iraq and western Iran. In 1847, the Ottomans and Persians agreed to make the Shatt al-Arab their common border; the Persian Empire also was given control of Khoramshahr and Abadan, areas on its western shore of the river that had large Arab populations.

Then in 1937, the now independent monarchies of Iraq and Iran signed an agreement that stipulated that their common border on the Shatt al-Arab was located at the low water mark on the eastern (i.e. Iranian) side all across the river’s length, except in the cities of Khoramshahr and Abadan, where the border was located at the river’s mid-point. In 1958, the Iraqi monarchy was overthrown in a military coup. Iraq then formed a republic and the new government made territorial claims to the western section of the Iranian border province of Khuzestan, which had a large population of ethnic Arabs.

In Iraq, Arabs comprise some 70% of the population, while in Iran, Persians make up perhaps 65% of the population (an estimate since Iran’s population censuses do not indicate ethnicity). Iran’s demographics also include many non-Persian ethnicities: Azeris, Kurds, Arabs, Baluchs, and others, while Iraq’s significant minority group comprises the Kurds, who make up 20% of the population. In both countries, ethnic minorities have pushed for greater political autonomy, generating unrest and a potential weakness in each government of one country that has been exploited by the other country.

The source of sectarian tension in Iran-Iraq relations stemmed from the Sunni-Shiite dichotomy. Both countries had Islam as their primary religion, with Muslims constituting upwards of 95% of their total populations. In Iran, Shiites made up 90% of all Muslims (Sunnis at 9%) and held political power, while in Iraq, Shiites also held a majority (66% of all Muslims), but the minority Sunnis (33%) led by Saddam and his Baath Party held absolute power.

In the 1960s, Iran, which was still ruled by a monarchy, embarked on a large military buildup, expanding the size and strength of its armed forces. Then in 1969, Iran ended its recognition of the 1937 border agreement with Iraq, declaring that the two countries’ border at the Shatt al-Arab was at the river’s mid-point. The presence of the now powerful Iranian Navy on the Shatt al-Arab deterred Iraq from taking action, and tensions rose.

Also by the early 1970s, the autonomy-seeking Iraqi Kurds were holding talks with the Iraqi government after a decade-long war (the First Iraqi-Kurdish War, separate article); negotiations collapsed and fighting broke out in April 1974, with the Iraqi Kurds being supported militarily by Iran. In turn, Iraq incited Iran’s ethnic minorities to revolt, particularly the Arabs in Khuzestan, Iranian Kurds, and Baluchs. Direct fighting between Iranian and Iraqi forces also broke out in 1974-1975, with the Iranians prevailing. Hostilities ended when the two countries signed the Algiers Accord in March 1975, where Iraq yielded to Iran’s demand that the midpoint of the Shatt al-Arab was the common border; in exchange, Iran ended its support to the Iraqi Kurds.

Iraq was displeased with the Shatt concessions and to combat Iran’s growing regional military power, embarked on its own large-scale weapons buildup (using its oil revenues) during the second half of the 1970s. Relations between the two countries remained stable, however, and even enjoyed a period of rapprochement. As a result of Iran’s assistance in helping to foil a plot to overthrow the Iraqi government, Saddam expelled Ayatollah Khomeini, who was living as an exile in Iraq and from where the Iranian cleric was inciting Iranians to overthrow the Iranian government.