On May 13, 1958, in what is historically called the “May 1958 Crisis”, thousands of European Algerians, supported by the French Algerian Army, seized power in Algiers, taking over government buildings and public installations. The French Algerian government of Governor-General André Mutter was deposed. In its place, a junta called the “Committee of Public Safety” (French: Comité De Salut Public) was formed, led by General Massu (whose efforts were instrumental in the French victory in the Battle of Algiers), as President; subsequently on May 23, 1958, this self-styled government was renamed the “Central Committee of Public Safety”, with General Massu and Dr. Mohammed Sid Cara, a moderate Algerian Muslim, both holding the positions of President. A full-scale rebellion was now underway.

(Taken from Algerian War of Independence – Wars of the 20th Century –Vol. 4)

In a public announcement, General Massu called for the return of General Charles de Gaulle to lead the government of France, declaring that only the retired but strong-willed military officer could keep Algeria from being broken off from France. General de Gaulle was widely esteemed in France, having served as commander of the Free French Forces in World War II and then as head of the provisional government after France’s liberation in 1944.

General Massu made preparations to overthrow the French government if his demand was not met, on May 24, 1958, sending French Algerian commandos who seized the French region of Corsica, and threatening to invade Paris with Algerian troops and mutinous armored units in mainland France. On May 19, nearly a week into the rebellion, General de Gaulle announced his readiness to return from retirement and lead the country but only on the condition that he be allowed to rule with broad powers for a period of six months. On May 28, Prime Minister Pflimlin’s government collapsed and the following day, President René Coty asked General de Gaulle to form a new government.

On June 1, 1958, France’s National Assembly named General de Gaulle the new Prime Minister, also granting the new government broad powers for six months. Three days later, on June 4, Premier de Gaulle traveled to Algeria and amid a large assembly of pieds-noirs in Algiers, he declared “Je vous ai compris” (“I have understood you.”) and on June 16, the words “Algérie Française” (“French Algeria”), which appeared to the European Algerians that the new French government was determined to hold onto Algeria. This supposition seemed warranted, as three months later, in October 1958, France initiated the Constantine Plan, an ambitious, multi-sectoral economic and social series of programs in Algeria that included agrarian reform, housing, civil service reforms, education, and infrastructure development. A ceasefire and amnesty also were offered to the FLN, which the latter rejected.

The French government did, however, end the militarized situation in Algiers, transferring army officers who had joined the rebellion to other posts outside Algeria. In December 1958, General Salan, who had held the position of Algerian Delegate-General (which had superseded the earlier position of Governor-General), was transferred to mainland France. Paul Delouvrier, an industrialist, took over as Delegate-General, marking the return of civilian rule in Algiers.

De Gaulle also took a hard-line position against the FLN, ordering in early 1959 the French Algerian forces, now led by General Maurice Challe, to escalate counter-insurgency operations. In what became known as the Challe Plan, the French Army launched a series of sweeping offensives in northern Algeria from west to east: the Oran region, Atlas Sahara, Algiers region, and Constantine region. Improved tactics that emphasized speed, surprise, and concentration of forces, and specially developed counter-insurgency military equipment gave the French full battlefield success: French elite units at the forefront of the fighting drove away the FLN, and captured areas were turned over and secured by the regular army and indigenous militias. In April 1960, General Challe was ready to achieve total victory with the upcoming Operation Trident, the offensive aimed at capturing the final (and strongest) FLN strongholds in the Aures Mountains. The attack would not be realized, however.

De Gaulle also was vested with powers to draw up a new constitution, which was completed by Michel Debré, the Minister of Justice. On September 28, 1958, in a referendum held in France, French Algeria (i.e. the overseas departments of Oran, Algiers, and Constantine), and France’s African, Pacific, and Atlantic colonies, a total of over 80% of the electorate (for the first time under universal suffrage) voted to approve the new constitution, which came into effect on October 4, 1958. The new charter strengthened the role of the president, who was given more executive powers (as de Gaulle had wanted) in order to solve the political instability that had plagued the French Fourth Republic.

In November 1958, in legislative elections that ushered in the French Fifth Republic, de Gaulle’s party, the Union for the New Republic (French: Union pour la Nouvelle République) won the most number of seats in the National Assembly. Then in the presidential election held the following month, de Gaulle won overwhelmingly as France’s new President; he took office on January 8, 1959.

The 1958 constitution also included the unprecedented provision that allowed France’s colonies to gain their independence subject to the colony’s vote in the referendum and the colony’s legislative assembly decision for independence. Nearly all of France’s African colonies voted to remain with France (albeit with greater political autonomy) under the newly formed “French Community” – only Guinea rejected the proposed constitution and gained its independence in October 1958.

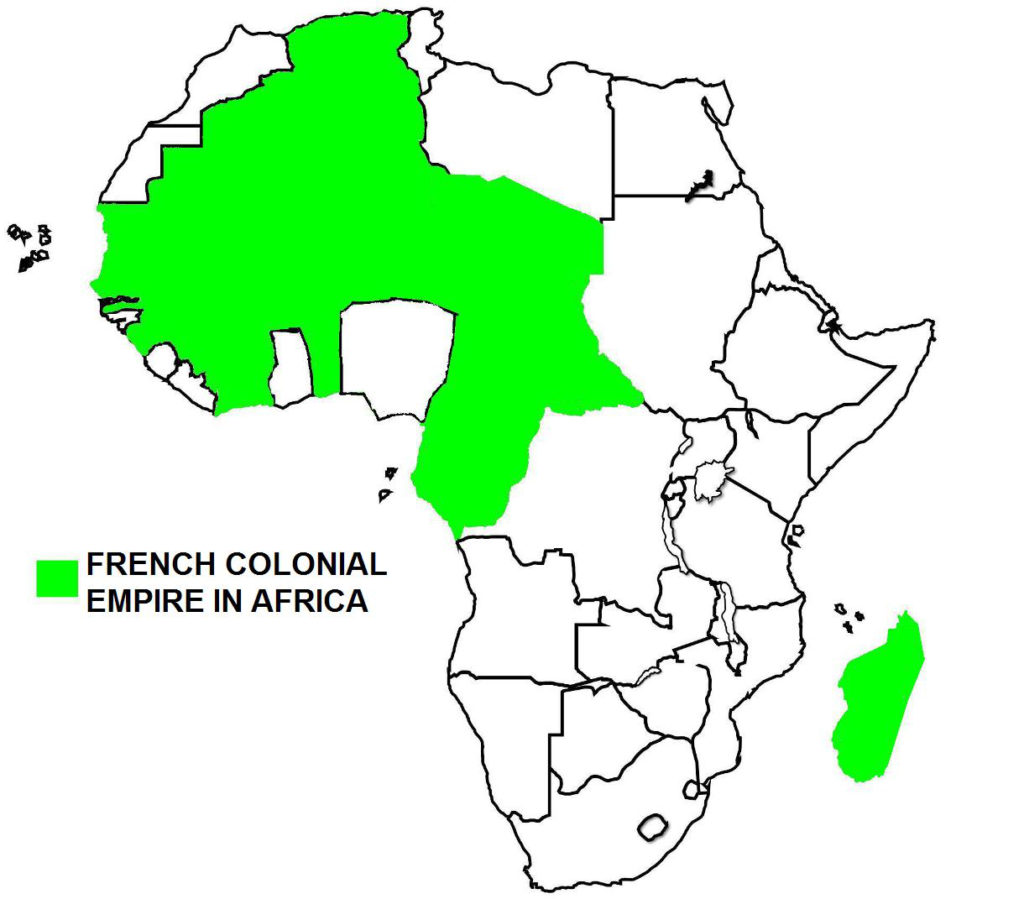

The “French Community” did not last long, however, and by the end of 1960, French West Africa (Figure 16) had ceased to exist with Cameroon, Togo, Mali, Senegal, Dahomey (now Benin), Niger, Upper Volta (now Burkina Faso), Ivory Coast, Chad, Central African Republic, Congo-Brazzaville, Gabon, and Mauritania, as well as Madagascar located off East Africa, gaining independence. De Gaulle’s moves to disengage from Africa did not bode well for the pieds-noirs, although Algeria, being an integral part of France, could not legally secede by way of the 1958 referendum. In any case, in the referendum, 97% of Algerians voted to remain a part of France.

Meanwhile, the FLN had vainly tried to stop Algerian Muslims from taking part in the referendum, with the FLN externals forming the Provisional Government of the Algerian Republic (GPRA; French: Gouvernement Provisionel de la République Algérienne), a government in exile based in Tunisia. The GPRA was the FLN’s attempt to gain political and diplomatic legitimacy in the international community (as well as to undermine France’s ongoing reforms in Algeria) and received recognition from many Arab countries.

The demise of French Algeria began on September 16, 1959 when de Gaulle declared that Algerians had the right of self-determination and offered three options regarding Algeria’s political future: independence from France; integration with France (the status quo); or “association” with France, i.e. a “government of Algerians by Algerians, supported by French aid in close union with France”. De Gaulle appeared to favor “association”. European Algerians were outraged at de Gaulle, as an independent Algeria meant losing their political and economic stranglehold on power. By sheer numbers alone, the pieds-noirs, who numbered about one million in the 1960s (10% of the population) would be overwhelmed demographically by Algerian Muslims, who totaled some nine million. French Algerians formed the French National Front (FNF), a militia aimed at opposing de Gaulle, who ironically had been put into power by the same militancy of the pieds-noirs and French Algerian Army.

France’s possessions in Africa included the vast French West Africa and French Equatorial Africa (shaded on the left).

De Gaulle further weakened the French Algerian Army’s radicalism when on January 19, 1960, he dismissed General Massu, victor of the Battle of Algiers, who had threatened insubordination by declaring that he and other officers may choose to not follow de Gaulle’s orders. Three months later, in April 1960, de Gaulle reassigned General Challe, commander-in-chief of the French Algerian Army, away from Algeria, just as the latter was on the verge of inflicting a decisive defeat on the FLN “internal” forces.

General Massu’s dismissal sparked the “Week of Barricades” (French: La semaine des barricades) starting on January 24, 1960, where some 30,000 pieds-noirs took to the streets, seized government buildings, and set up barricades in an act of defiance against de Gaulle’s government. Viewing these acts as a threat to his regime, de Gaulle, donning his World War II brigadier general’s uniform in a televised broadcast on January 29, 1960, appealed to the French people and armed forces to remain loyal to France. The French 10th Parachute Division, which had won the Battle of Algiers for France, did not launch suppressive action against the barricades, but the refusal of the French Army to join the protesters doomed the uprising. The French 25th Parachute Division finally broke up the barricades; casualties for the protesters were 22 dead and 147 wounded, and for the Algerian gendarmes (police), 14 dead and 123 wounded.