In March 1975, North Vietnam launched its spring offensive that would finally bring the war to an (abrupt) end. Under Campaign 275, on March 10, North Vietnamese forces attacked Ban Me Thout, which was captured after eight days of fighting; the whole Dak Lak Province then fell. On the desperate appeal of the U.S. Ambassador to South Vietnam, President Ford asked U.S. Congress for emergency assistance to South Vietnam, but American legislators, now viewing South Vietnam as lost, instead cut appropriations to that country by 50%. In North Vietnam, encouraged by this victory, military planners moved to capture Pleiku, Ton Kum and the whole Central Highlands (South Vietnam’s II Corps Tactical Zone).

(Taken from Vietnam War – Wars of the 20th Century – Twenty Wars in Asia – Vol. 5)

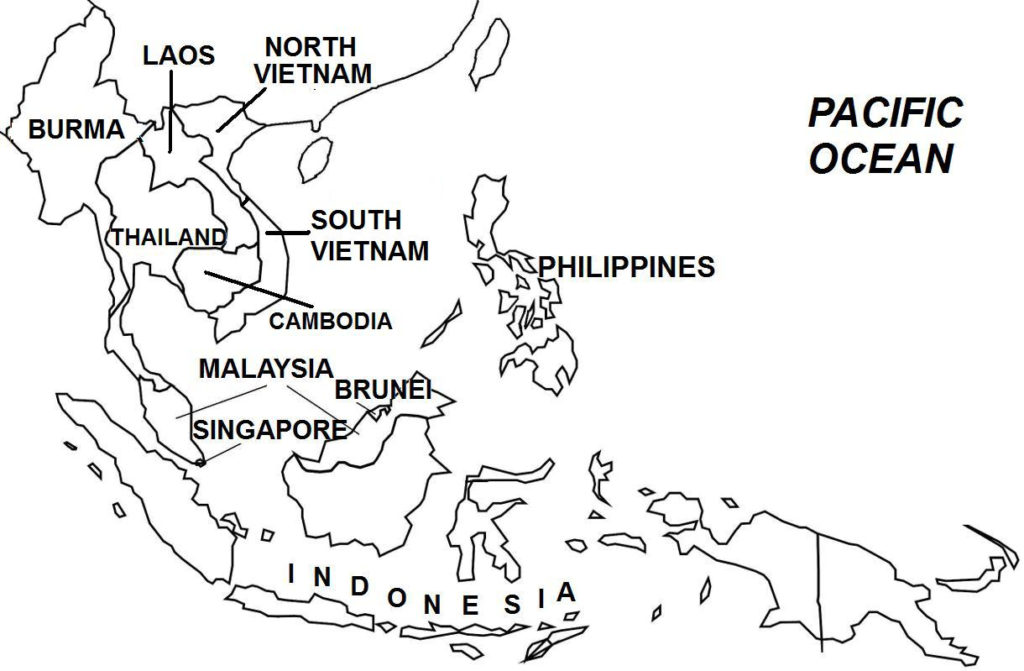

Toward the end In March 1974, North Vietnam launched a series of “strategic raids” from the captured territories that it held in South Vietnam. By November 1974, North Vietnam’s control had extended eastward from the north nearly to the south of the country. As well, North Vietnamese forces now threatened a number of coastal centers, including Da Nang, Quang Ngai, and Qui Nhon, as well as Saigon. Expanding its occupied areas in South Vietnam also allowed North Vietnam to shift its logistical system (the Ho Chi Minh Trail) from eastern Laos and Cambodia to inside South Vietnam itself. By October 1974, with major road improvements completed, the Trail system was a fully truckable highway from north to south, and greater numbers of North Vietnamese units, weapons, and supplies were being transported each month to South Vietnam.

North Vietnam’s “strategic raids” also were meant to gauge U.S. military response. None occurred, as at this time, the United States was reeling from the Watergate Scandal, which led to President Nixon resigning from office on August 9, 1974. Vice-President Gerald Ford succeeded as President.

Encouraged by this success, in December 1974, North Vietnamese forces in eastern Cambodia attacked Phuoc Long Province, taking its capital Phuoc Binh in early January 1975 and sending pandemonium in South Vietnam, but again producing no military response from the United States. President Ford had asked U.S. Congress for military support for South Vietnam, but was refused.

In March 1975, North Vietnam launched its spring offensive that would finally bring the war to an (abrupt) end. Under Campaign 275, on March 10, North Vietnamese forces attacked Ban Me Thout, which was captured after eight days of fighting; the whole Dak Lak Province then fell. On the desperate appeal of the U.S. Ambassador to South Vietnam, President Ford asked U.S. Congress for emergency assistance to South Vietnam, but American legislators, now viewing South Vietnam as lost, instead cut appropriations to that country by 50%. In North Vietnam, encouraged by this victory, military planners moved to capture Pleiku, Ton Kum and the whole Central Highlands (South Vietnam’s II Corps Tactical Zone).

Meanwhile, on March 14, 1975, President Thieu, meeting with his top commanders, ordered that South Vietnamese forces in the northern half of the country (I Corps and II Corps Tactical Zones) conduct an orderly withdrawal to the southern half (III Corps and IV Corps Tactical Zones), or the nation’s major economic and industrial centers. Also for the Central Highlands, the South Vietnamese military did not have the men and resources to defend that region, and the forces there were ordered to withdraw. On March 16, 1975, some 80,000 South Vietnamese troops in Pleiku and Ton Kum began their retreat to coastal Tuy Hoa, which in the following days, turned into chaos as tens of thousands of civilians, panic-stricken at being abandoned, also fled, causing delays by crowding the narrow, poorly maintained roads. North Vietnamese forces, soon learning of the withdrawal, shelled the roads with artillery fire, inflicting heavy casualties and soon causing the retreat to be called the “column of tears”. In total, only 20,000 of 60,000 South Vietnamese soldiers reached Tuy Hoa, and II Corps was effectively destroyed as a fighting unit. Civilian losses also were immense: 120,000 killed, missing, and captured, while 60,000 survived.

Also as part of the Spring Offensive, in March 1975, North Vietnamese forces, numbering 100,000 soldiers and supported by tanks and artillery, launched a multi-pronged offensive in the northern provinces (Quang Tri, Thua Thien, Quang Nam, and Quang Tin; South Vietnam’s I Corps Tactical Zone), attacking from the north, west, and south aimed at pushing back South Vietnamese forces to Da Nang (Figure 5) and destroying them there. President Thieu, who had envisaged a string of defensive positions along the coastal areas from where I Corps units would make a fighting retreat, now issued a series of contradictory orders to his commanders regarding whether to defend or abandon Hue. Then as Quang Tri and Hue in the north and Chu Lai and Tam Ky in the south became indefensible, South Vietnamese units withdrew to Da Nang, and retreating troops were joined by tens of thousands of panic-stricken civilians, and in a repeat of the debacle at the Central Highlands, the withdrawal turned into a chaotic, desperate retreat, all the while being subject to North Vietnamese artillery fire. Some 100,000 South Vietnamese soldiers and two million civilians were soon packed at Da Nang, which came under North Vietnamese artillery fire that that killed tens of thousands of people. The city was soon surrounded on three sides, with North Vietnamese forces blocking all roads to the city. Then in the frenzied evacuation by air and sea from Da Nang, with few transports available, only 16,000 soldiers and 50,000 civilians escaped. Some 70,000 South Vietnamese troops and two million civilians were trapped in the city, and were captured by North Vietnamese forces. Soon thereafter, the remaining northern coastal towns and cities fell without resistance, and the northern provinces were captured. Within a few weeks, the northern half of South Vietnam had collapsed without much resistance. The rapid North Vietnamese advance shocked the international community.

North Vietnamese leaders, who also were surprised by their quick successes, now decided to advance their timeline for conquering South Vietnam by 1976 to capturing Saigon by May 1, 1975. The offensive on Saigon, called the Ho Chi Minh Campaign and involving some 150,000 troops and supplied with armor and artillery units, began on April 9, 1975 with a three-pronged attack on Xuan Loc, a city located 40 miles northeast of the national capital and called the “gateway to Saigon”. Resistance by the 18,000-man South Vietnamese garrison (which was outnumbered 6:1) was fierce, but after two weeks of desperate fighting by the defenders, North Vietnamese forces had broken through, with the road to Saigon now lying open.

In the midst of the battle for Xuan Loc, on April 10, 1975, President Ford again appealed to U.S. Congress for emergency assistance to South Vietnam, which was denied. South Vietnamese morale plunged even further when on April 17, 1975 neighboring Cambodia fell to the communist Khmer Rouge forces. On April 21, 1975, President Thieu resigned (and went into exile abroad) and was replaced by a government to try and negotiate a settlement with North Vietnam. But the latter, by now in an overwhelmingly superior position, rejected the offer.

By April 27, 1975, some 130,000 North Vietnamese troops had encircled Saigon, with some intense fighting breaking out at the outskirts and bridges at the city’s approaches. The South Vietnamese military set up five defensive lines north, west, and east of Saigon, manned by 60,000 troops and augmented by other units that had retreated from the north. However, by this time, the South Vietnamese forces were verging on collapse, with morale and discipline breaking down, desertions widespread, and ammunition and supplies running low. In Saigon, desperation and anarchy reigned, with the government’s imposition of martial law failing to quell the panic-stricken population.

The end came on April 30, 1975 when North Vietnamese forces, after launching an artillery barrage on the city one day earlier, attacked Saigon and entered the city with virtually no opposition, as the South Vietnamese military high command had ordered its troops to lay down their weapons. The Mekong Delta south of Saigon soon also fell. By early May 1975, the war was over.

In the lead-up to Saigon’s fall, thousands of South Vietnamese made a desperate attempt to leave the country. As early as March 1975, the U.S. government had begun to evacuate its citizens and other foreign nationals, as well as some South Vietnamese civilians. In April 1975, the U.S. launched Operation New Life, where some 110,000 South Vietnamese were evacuated, the great majority consisting of South Vietnamese military officers, Catholics, bureaucrats, businessmen, locals employed in U.S. military and civilian facilities, and other Vietnamese who had cooperated or associated with the United States and thus were considered to be potential targets for North Vietnamese reprisals. Also in the final days of the war, the U.S. military conducted Operation Frequent Wind, where the remaining U.S. nationals and American troops (U.S. Marines) were evacuated by helicopters from the Defense Attaché Compound and U.S. Embassy in Saigon onto U.S. ships waiting offshore. The chaotic evacuation, which succeeded in moving over 7,000 Americans and South Vietnamese, was captured in film, with dramatic camera footage showing thousands of frantic South Vietnamese civilians crowding the gates of the U.S. Embassy, and helicopters being thrown overboard the packed decks of U.S. carriers to make room for more evacuees to arrive.

Some 58,000 U.S. soldiers died in the Vietnam War, with 300,000 others wounded. South Vietnamese casualties include: 300,000 soldiers and 400,000 civilians killed, with over 1 million wounded. North Vietnamese and Viet Cong human losses are variously estimated at between 450,000 and over 1 million soldiers killed and 600,000 wounded; 65,000 North Vietnamese civilians also lost their lives.