General Francisco Franco did not have the means to transport his “Army of Africa” to mainland Spain, as the Republican Navy blockaded the southern coastal waters. He turned for support to Germany and Italy, two fascist countries led by Adolf Hitler and Benito Mussolini, respectively, which agreed to provide military assistance. Hitler and Mussolini perceived the Nationalists’ relationship with the Falangists (Spanish fascists) as aligning with Fascism; the two fascist leaders also loathed at the Republican government’s association with the socialists and communists, viewing it as aligning with the Soviet Union and Marxism.

(Taken from Spanish Civil War – Wars of 20th Century – Volume 3)

War On July 17, 1936, Spain’s forces in Spanish Morocco declared in a radio broadcast a state of war against the central government in Madrid, an act of rebellion that opened the Spanish Civil War. These overseas forces, called the “Army of Africa”, were the Spanish Army’s strongest fighting units and consisted of the Spanish Legion and Moroccan regiments. The Army of Africa would contribute significantly to the outcome of the land operations in the coming war.

Earlier, local authorities in Spanish Morocco had learned of the plot. As a result, the rebels were forced to move forward the uprising from the previously planned schedule of 5 AM on July 18. Shortly after the rebellion was broadcast, the Army of Africa gained control of Spanish Morocco, in the process also killing dozens of persons, including pro-government army officers and civilian leaders.

By this time, General Franco, who previously had commanded the Army of Africa and from whom he drew great respect, arrived from the Canary Islands (which also had risen up in rebellion) and took over-all command in Spanish Morocco. As agreed, the next day, July 18, many military commands in mainland Spain also declared war; thus, a large-scale army rebellion was underway.

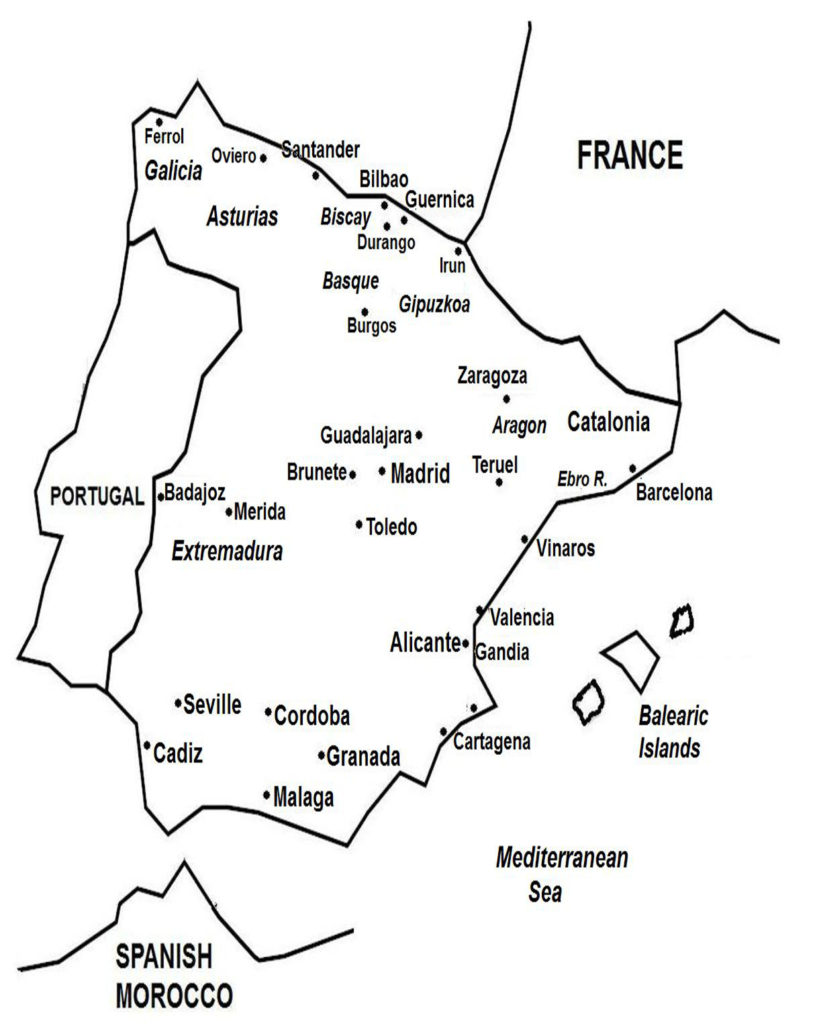

Many other military commands, however, did not revolt or were put down while doing so. The uprisings succeeded in the southwest and in a large swathe from the coastal northwest to northern central Spain, Spanish Morocco, the Canary Islands, and most of the Balearic Islands – in total, about one-third of the country.

The government succeeded in holding onto nearly the whole eastern half of mainland Spain, the northern coastal provinces, and all the major cities including Madrid, Barcelona, Bilbao, Valencia, and Malaga – in total, about two-thirds of Spain. Many areas had been won on the government side through the efforts of socialist and communist militias who, together with loyal local police units, sealed of and barricaded rebelling military garrisons, and then forced the trapped army units inside to surrender. At the start of the army rebellion, the government had refused to heed the calls of socialist and communist leaders to arm the civilian population. Because of the emerging crisis, Prime Minister Santiago Casares resigned from office; his successor, Prime Minister José Giral then issued instructions to distribute firearms to the people.

The Spanish Army itself became divided, with about an equal number of units joining either side of the conflict; most army officers aligned with the rebels. The small Spanish Air Force remained loyal to the government, as did the Spanish Navy. The insurgents, however, seized a number of ships in Ferrol early in the war.

The rebels now realized that the uprising had failed to topple the government, and worse, their military resources were inadequate to defeat the forces that remained loyal to the government. In turn, the government was incapable of quickly ending the rebellion. As a result, the crisis appeared headed toward a protracted war.

The rebels became known as “Nationalists”, while supporters of the country’s republican government were called “Republicans”. Drawn to the Nationalists’ cause were landowners, urban elite, monarchists, right-wing politicians, and the Catholic Church (including most of the clergy). Supporting the Republicans were democracy-advocating leftist politicians, socialists, and communists. The anarchists, whose strongholds were in Catalonia and Aragon, were opposed ideologically to both sides of the war, but nominally supported the Republicans.

The Nationalists divided their forces into two commands: the northern force, led by General Mola, who operated in northern Spain; and the southern force, led by General Franco, who operated in southern Spain. General Franco did not have the means to transport his “Army of Africa” to mainland Spain, as the Republican Navy blockaded the southern coastal waters. He turned for support to Germany and Italy, two fascist countries led by Adolf Hitler and Benito Mussolini, respectively, which agreed to provide military assistance. Hitler and Mussolini perceived the Nationalists’ relationship with the Falangists (Spanish fascists) as aligning with Fascism; the two fascist leaders also loathed at the Republican government’s association with the socialists and communists, viewing it as aligning with the Soviet Union and Marxism.

As a result, German military transport planes soon arrived in Spain, and for two weeks starting on July 27, 1936, transported thousands of General Franco’s troops from Spanish Morocco to Seville, Spain. The German (and Italian) involvement in the war would prove decisive. Within months after the outbreak of war, large shipments of German planes, tanks, and artillery units would enhance the Nationalists’ war effort, and German Navy ships patrolled the southern Mediterranean waters.

Germany’s most significant contribution was its Condor Legion, a small but potent air force consisting of German fighters, bombers, and support aircraft that achieved virtual control of the sky and carried out bombing attacks on many Republican towns and cities. German military leaders in Berlin also followed developments in Spain with great interest, as the war allowed them to assess the performance of German weapons in combat, as well as to develop new battle techniques. Germany made great efforts to conceal its involvement in the war, and sent the cargo ships carrying the weapons to Portugal. From there, the Portuguese government, at that time ruled by a right-wing, authoritarian regime that was allied with the Spanish Nationalists, turned over the weapons to the rebels.

In numerical terms, Italy’s contribution to the Nationalists’ war effort was greater than that of the Germans. In addition to 600 plans, 150 tanks, 800 artillery pieces, and 240,000 firearms, Italy also sent some 50,000 volunteers (organized as the Corpo Truppe Volontarie) who fought on the rebels’ side. The Italian Navy also had a strong presence on Spanish maritime waters and provided naval artillery support for the Nationalist offensives at Malaga, Valencia, and Barcelona.

The German and Italian air and naval presence ultimately ended the Republican Navy’s blockade of southern Spain, allowing Nationalist ships to transport other units of the Army of Africa from northern Africa to southern Spain.

By August 1936, General Franco had taken control of much of southeastern Spain, including Granada, Cordoba, and Cadiz; Huelva was captured the following month. Nationalist forces advanced north and captured the towns of Merida and Badajoz, also in August 1936. These latest victories allowed the Nationalists to link up their northern and southern zones; in September 1936, the forces of Generals Franco and Mola established physical contact.