Casualties in the Axis invasion of Yugoslavia were: Germans: 150 killed, 400 wounded, 15 missing; Italians: 3,000 killed or wounded; Hungarians: 120 killed, 200 wounded, 13 missing; Yugoslavians: thousands of civilians and soldiers killed, 350,000 prisoners.

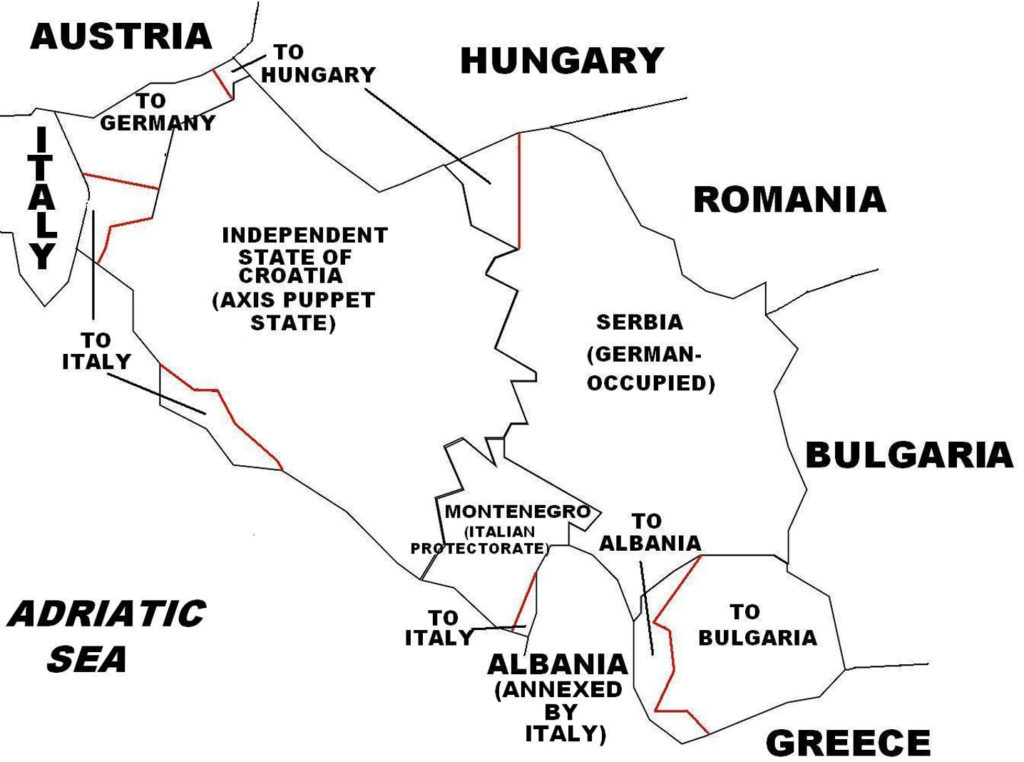

By the terms of surrender, the Axis dissolved Yugoslavia, and partitioned its territories or allowed the formation of quasi-independent states under Axis control. Germany annexed northern Slovenia, occupied much of Serbia which was placed under a collaborationist regime called the “Government of National Salvation”, and controlled the fascist “Independent State of Croatia”. Italy acquired the rest of Slovenia, Kosovo, Montenegro, and parts of the Dalmatian coast. Hungary annexed areas of northern Yugoslavia. Bulgaria, which did not participate in the invasion, occupied Macedonia.

(Taken from Invasion of Yugoslavia – Wars of the 20th Century – World War II in Europe – Volume 6)

The war lasted twelve days, but the easy Axis victory in Yugoslavia proved deceptive, as within a few months, local armed militias launched an effective guerilla struggle that would beleaguer the occupation forces and tie down large numbers of Axis forces that would be later needed in other theaters of World War II.

Invasion of Yugoslavia On April 6, 1941, several air fleets of the Luftwaffe (German Air Force), flying from bases in Austria and Romania, launched a massive two-day night and day bombardment of Belgrade, the Yugoslavian capital. This air campaign, which involved 500 warplanes including bombers and fighters, was launched under Operation Punishment, the code name reflecting Hitler’s anger resulting from the Yugoslav military coup two weeks earlier (March 27), and was meant to inflict maximum indiscriminate destruction on the Yugoslavian capital. Instead, the Luftwaffe modified the attack and directed the planes to important government and military targets in Belgrade, which resulted in the destruction of the royal palace, army headquarters and military barracks, postal and telegraph centers, power stations, and railway lines. Thousands of civilians were killed in the raids.

The German air attacks on Belgrade were devastating strategically for the Yugoslav High Command, as the loss of the central communications network meant that the military was cut off from all contact with its various regional commands. Also in this way, the Yugoslav central government lost all communication with regional and local administrations across the country. Thereafter, German planes attacked airfields, military centers, and regional communication lines across Yugoslavia. The Germans were greatly aided by the defection of a Yugoslav Air Force pilot who brought along with him the locations of many small secret air fields scattered across Yugoslavia.

On April 6, 1941, coinciding with the air attacks on Belgrade, elements of the German Twelfth Army based in western Bulgaria, crossed the border into northern Macedonia (southern Yugoslavia) and advanced toward Skopje, which they captured the next day. The whole region soon came under German control, which was important in many ways: German forces could now launch the invasion of Greece (next article); the lines of communication between the Yugoslav Army in the north and its Greek and British allies in the south were cut; and the Yugoslav Army’s contingency plan to escape to the south via northern Macedonia was cut off.

Before the outbreak of fighting, the Yugoslav High Command was confident that its forces could slow down or even stop a German invasion, for a number of reasons. First, Yugoslavia’s rugged terrain of tall mountains, steep narrow passes, and few roads, was a formidable obstacle to conducting swift military movements. The rivers and waterways in the inhospitable northern frontier served as a natural first line of defense. Second, the Yugoslav military was known to be formidable, boasting 1 million soldiers, 200 tanks, and 600 planes. Some 80% of its troops were deployed along the country’s 1,900-mile border with Italy, Austria, Hungary, Romania, Bulgaria, Albania (all hostile or potentially hostile), and Greece (its only regional ally). So confident was the Yugoslav government that Prime Minister Dusan Simovic stated that the German attack would be “the beginning of Hitler’s downfall”. Third, Yugoslavia believed that its official neutrality spared it from an invasion, and so did not fully mobilize its forces so as not to provoke Hitler. Just days before the Germans invaded, the Yugoslav government deemed that it still had several months to consider its political and military options.