On April 17, 1975, the Khmer Rouge, a Cambodian communist rebel group, emerged victorious in the Cambodian Civil War (previous article) when its forces captured Phnom Penh, overthrew the United States-backed government of the Khmer Republic, and took over the reins of power. In January 1976, the Khmer Rouge ratified a new constitution, which changed the country’s name to “Democratic Kampuchea” (DK). In the Western press, DK, as well as the new Cambodian government, continued to be referred to unofficially as “Khmer Rouge”.

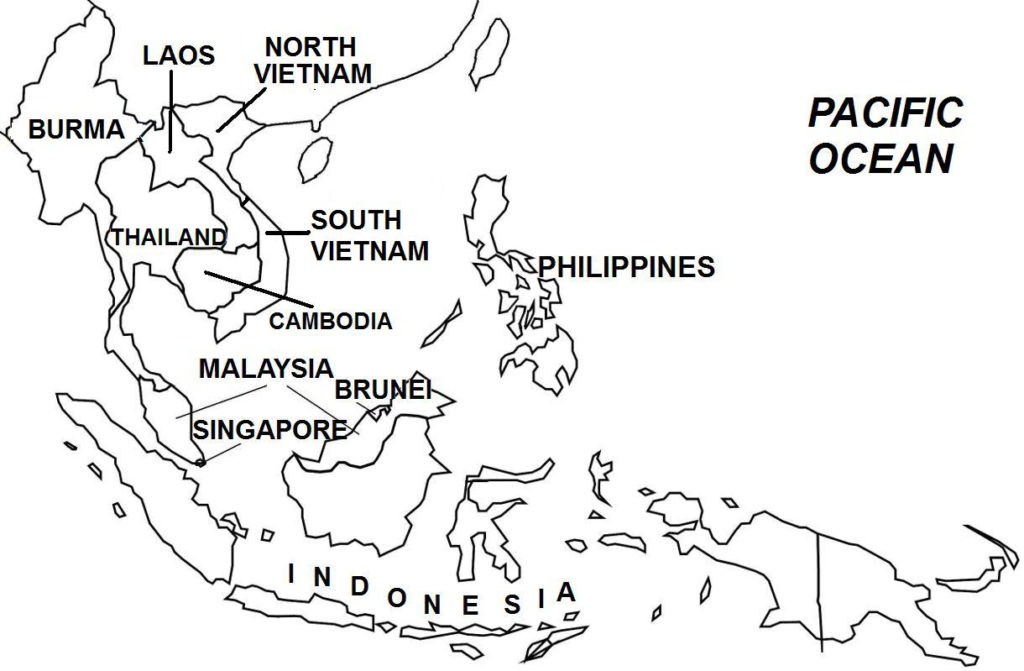

Cambodia in Southeast Asia

In April 1976, the Khmer Rouge’s newly formed legislature, called the Kampuchean People’s Representative Assembly, elected the country’s new government with Pol Pot (whose birth name was Saloth Sar) appointed as Prime Minister. In September 1976, Pol Pot declared that his government was Marxist-Leninist in ideology that was closely allied with Chairman Mao Zedong’s Chinese Communist Party. The following year, September 1977, he revealed the existence of Kampuchea’s state party called the Kampuchean Communist Party, also stating that it had been formed 17 years earlier, in September 1960. These disclosures confirmed the long-held belief by international observers that the Khmer Rouge was a communist organization, and that DK was a one-party totalitarian state.

(Taken from Cambodian Genocide – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 5)

Pol Pot had long held absolute power in the Khmer Rouge and (secretly) held the position of General Secretary of the party since 1963 behind the façade of a front organization called Angkar Padevat (“Revolutionary Organization”, usually shortened to Angkar, meaning “Organization”). Ostensibly, Angkar was politically moderate, as its leaders were former high-ranking Cambodian government officials who held only moderate leftist/socialist beliefs. However, behind the scenes, hard-line communist party ideologues controlled the movement.

During the Cambodian Civil War, the Khmer Rouge operated behind the cover of Prince Norodom Sihanouk, the deposed Cambodian ruler who was widely popular among the Cambodian masses, through a political-military alliance called the Royal Government of the National Union of Kampuchea, or GRUNK (French: Gouvernement royal d’union nationale du Kampuchéa). GRUNK supposedly was a coalition of all opposition movements, and was nominally controlled by Sihanouk as its head of state. When the Khmer Rouge seized power in April 1975, Sihanouk continued to hold the position of head of state under the new Khmer Rouge regime, but held no real political power. In April 1976, after resigning as head of state, he was placed under house arrest.

In foreign relations, DK isolated itself from much of the international community. Shortly after coming to power, the remaining 800 foreign nationals in Cambodia were gathered at the French Embassy in the capital, and then trucked out of the country through the Thai border. All foreign diplomatic missions in Kampuchea were closed down. However, when the DK government later was granted a seat at the United Nations (UN) to represent Kampuchea (Cambodia’s new name), a small number of foreign embassies were allowed to reopen in Phnom Penh. But as foreign travel to Kampuchea was severely restricted, the country was virtually cut off from the outside world. As a result, apart from official government pronouncements, practically nothing was known in the outside world about the true conditions in the country during the Khmer Rouge regime.

At the core of the Khmer Rouge’s Marxist ideology was the regime’s desire to achieve the purest form of communism, that of a classless society. The Khmer Rouge also advocated ultra-nationalism and anti-imperialism, and desired to eliminate foreign control and achieve national self-sufficiency, first through the phased, collectivized agricultural development of the countryside. Before coming to power, the Khmer Rouge had rejected the advice of Chinese communist leaders who told them that the process of transition from socialism to communism should not be rushed. But the Khmer Rouge, particularly its leader Pol Pot, was determined to achieve communism rapidly without the transitional phases of socialism.

The Khmer Rouge first implemented its concept of communism sometime in 1970 at Ratanakiri Province in the northeast, where it forced the local population to move from villages to agrarian communes. The Khmer Rouge also carried out other forced relocations at Steung Treng, Kratie, Banam and Udong. In 1973, the Khmer Rouge concluded that the “final solution” to end capitalism in Cambodia was to empty all the towns and cities, and move all Cambodians to the rural areas. Simultaneously, in areas under its control, the Khmer Rouge executed teachers, local leaders, traders, and other “counter-revolutionaries”. As well, all forms of dissent or opposition were met with brutal reprisals. By 1974, the Khmer Rouge was carrying out indiscriminate killings of men, women, and children. The rebels also destroyed villages, such as those that occurred in Odongk and Ang Snuol districts, Sar Sarsdam village, and other areas.

The Cambodian government soon received reports of these brutalities being committed by the Khmer Rouge, but ignored them. An invaluable insight into the workings of the Khmer Rouge came in 1973 (two years before the rebels came to power) when a former school teacher, Ith Sarin, went to the northwest and central regions and joined the Khmer Rouge. Eventually, Ith Sarin become disillusioned and left, and returned to the fold of the law. His work, Regrets for the Khmer Soul (Khmer: Sranaoh Pralung Khmer), revealed that the Khmer Rouge was a Marxist organization that operated behind a front movement called “Angkar”. Angkar had a well-structured organization that imposed brutal, repressive policies in controlled areas, which it called “liberated zones”.

The Cambodian government banned Ith Sarin’s book and jailed its author for being a communist sympathizer. Then, a report by an American diplomatic officer, Kenneth Quinn, which described Khmer Rouge atrocities in eastern and southern Cambodia, was also ignored, this time by U.S. authorities. Contemporary news reports by some American newspapers (e.g. The New York Times, Baltimore Sun), which described the Khmer Rouge carrying out massacres, executions, and forced evacuations, also escaped scrutiny by the U.S. government.

On April 17, 1975, a few hours after capturing Phnom Penh, the Khmer Rouge ordered all residents to leave their homes and move to the countryside. The order to leave was both urgent and mandatory – those who resisted would be (and were) killed. There were no exceptions, and even the sick and elderly were ordered to leave. Hospitals were closed down and the patients, regardless of their medical conditions, were evacuated, some still in their beds and attached to intravenous tubes.

Within a few days, Phnom Penh was completely depopulated, with all its residents – some 2.5 million (30% of the country’s population) and ordered to take only a few belongings – making their way in long convoys in ox carts, motorbikes, scooters, and bicycles, but mostly on foot, to rural areas across the country. The Khmer Rouge’s order was for all persons to return to their ancestral villages.

In later testimonies, genocide survivors said of being told by Khmer Rouge cadres that the evacuation was being undertaken because American planes were about to bomb the city, or that the Khmer Rouge was conducting operations to flush out remaining government soldiers hiding in the city, or that U.S. Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) agents were planning to launch subversive actions in Phnom Penh to undermine the revolution, etc. Other survivors said of being told that their destination was only “two or three kilometers away” and that they could return “in two or three days”.