On April 6, 1994, Rwandan President Habyarimina and Burundi’s head of state, Cyprien Ntaryamira, were killed by undetermined assassins when their plane was shot down by a rocket-propelled grenade as it was about to land in Kigali. A staunchly anti-Tutsi military government took over power in Rwanda. Within a few hours and in reprisal for the double assassinations, the new government unleashed the Interahamwe “death squads” to murder Tutsis and moderate Hutus on sight. Over the next several weeks, in the event known as the “Rwandan Genocide”, large numbers of civilians were murdered in Kigali and throughout the country. No place was safe; in some instances, even Catholic churches were the scenes of the massacres of thousands of Tutsis where they had taken refuge.

The attackers used clubs, spears, firearms, and grenades, but their main weapon was the machete, with which they had trained extensively and which they used to hack away at their victims. At the urging of local officials, Hutu civilians joined in the killing frenzy, and turned against their Tutsi neighbors, acquaintances, and even relatives. In many cases, the threat of being killed for appearing sympathetic to Tutsis forced many otherwise disinterested Hutus to participate.

(Taken from Rwandan Civil War and Genocide – Wars of the 20th Century– Vol. 2)

The Rwandan Army provided the Interahamwe with a list of Tutsis to be killed, and raised road blocks to prevent any escape. The death toll in the Rwandan Genocide ranges from between 800,000 to one million; some 10% of the fatalities were moderate Hutus. The genocide lasted for about 100 days, from between April 6 to July 15, producing a killing rate of 10,000 persons a day. The speed by which it was carried out makes the Rwandan Genocide the fastest in history. (By comparison, the Holocaust in Europe during World War II, although producing a much higher death toll, was carried out over a number of years.)

Background Rwanda, a small country in Africa, experienced a long period of ethnic unrest before and after it gained its independence in the 1960s. Then in the 1990s, this unrest culminated in two events known as the Rwandan Civil War and the Rwandan Genocide, both of which caused great loss in human lives and massive destruction of the country.

The conflict revolved around the hostility between Rwanda’s two main ethnic groups, the majority Hutus, who comprised 85% of the population, and the Tutsis, who made up 14% of the population. The origin of this hostility goes back many centuries to when a Tutsi monarchy was established in the Hutu-populated land of what is present-day Rwanda. Over time, the Tutsi monarch gained domination over the Hutus. The Tutsi monarch also acquired ownership over most of the land, which he divided into vast estates that were overseen by a hierarchy of Tutsi overlords, and worked by Hutu laborers in a feudal-type system. For the most part, however, Tutsis and Hutus lived in harmony. In the course of time, some Hutus became wealthy, while many ordinary, non-aristocratic Tutsis remained poor.

Starting in the 1880s, Africa came under the control of the European powers who vied for a share of the vast continent in the event known as the “Scramble for Africa”. In Rwanda, the Tutsi monarchy fell under the domination of Germany, and during and after World War I, of Belgium. During the colonial period, the Belgians in particular, emphasized ethnic distinction of the indigenous peoples, and issued ethnic identity cards to natives that indicated if the card holder was a Tutsi, Hutu, or Twa (Twa is a Rwandan tribe that comprises only 1% of the population). The Belgians retained the Tutsi monarch as overlord of the colony and appointed Tutsis to administrative positions in the colonial government. The Belgians believed that Tutsis were racially superior to Hutus. The Belgian policies were resented by Hutus, sowing the seeds of the future conflict.

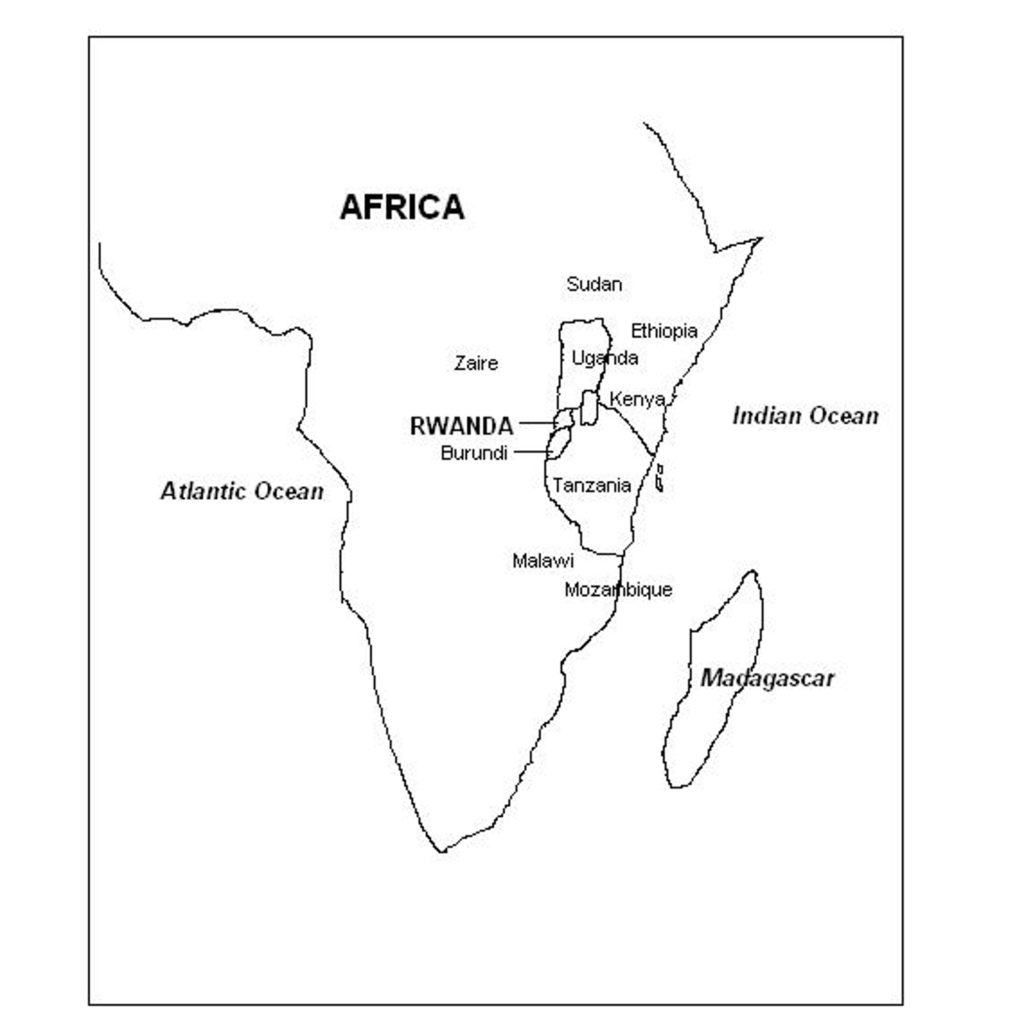

During the colonial period, Rwanda formed the northern portion of the Belgian colony of Ruanda-Urundi, with the southern half being present-day Burundi (Map 23). Then as a result of growing African nationalism after World War II, the European powers gradually were granting independences to their African colonies. To prepare for Ruanda’s transition to democracy, the Belgians convinced the Tutsi monarch to abolish feudalism. The Belgians allowed multi-party politics, causing political parties to form – along ethnic lines. Over the previous years, tensions had risen between Hutus and Tutsis. By the late 1960s as the Belgians prepared to decolonize in the lead-up to Ruanda’s independence, Hutus and Tutsis had become confrontational with each other; violence appeared likely to break out anytime.

Then in November 1959, a Tutsi mob attacked a Hutu politician who was then reported (erroneously) to have been killed in the attack. Hutu armed gangs launched massive retaliatory attacks against Tutsis in Kigali, Ruanda’s capital, and in other areas. Some 20,000 to 100,000 Tutsis were killed, while 150,000 others fled to nearby Urundi, Uganda, Zaire, and Tanzania. The Ruandan Tutsi monarch fled into exile to escape the violence.

Then in a referendum held in 1960, Ruandans voted overwhelmingly to abolish the monarchy. A year earlier, Hutu politicians had scored a decisive victory in the local elections. By a United Nations (UN) mandate, Ruanda-Urundi was dissolved and replaced by two successor countries, Rwanda and Burundi, both of which gained their independences on July 2, 1962. In the decades that followed their independences, the events in each country would have a profound effect on the other country. Rwanda was established as a democracy, but the Hutus who gained political power ruled the country as a Hutu autocratic state.

The Tutsis who fled the 1959 violence into neighboring countries soon militarized, forming armed groups that launched hit-and-run attacks into Rwanda. One particularly aggressive attack took place in late 1963, when Tutsi rebels based in Uganda came to within the vicinity of Kigali before being driven back by the Rwandan Army.

Map 23: Africa showing location of Rwanda and other East African countries.