At Hue, in central Vietnam, the North Vietnamese and Viet Cong forces of the Tet Offensive, who had seized large sections of the city, were ordered to remain and defend their positions. A 28-day battle ensued, with U.S. forces, supported by naval and ground artillery and air support, advancing slowly and engaging the enemy in intense house-to-house battles. By late February 1968 when the last North Vietnamese/Viet Cong units had been driven out of Hue, some 80% of the city had been destroyed, 5,000 civilians killed, and over 100,000 people left homeless. Combat fatalities at the Battle of Hue were 700 American/South Vietnamese and 8,000 North Vietnamese/Viet Cong soldiers.

(Taken from Vietnam War – Wars of the 20th Century – Twenty Wars in Asia)

Tet Offensive In early 1967, North Vietnam began preparing for a massive offensive into South Vietnam. This operation, which later came to be known as the Tet Offensive, would have far-reaching consequences on the outcome of the war. The North Vietnamese plan to launch the Tet Offensive came about when political hardliners in Hanoi succeeded in sidelining the moderates in government. As a result of the hardliners dictating government policies, in July 1967, hundreds of moderates, including government officials and military officers, were purged from the Hanoi government and the Vietnamese Communist Party.

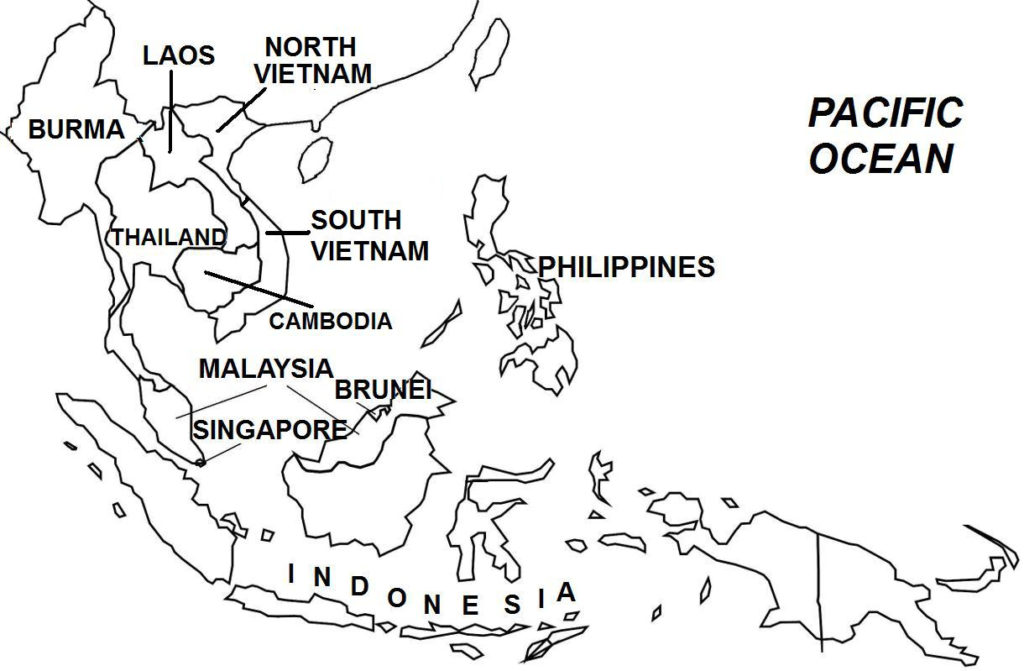

By fall of 1967, North Vietnamese military planners had set the date to launch the Tet Offensive on January 31, 1968. In the invasion plan, the Viet Cong was to carry out the offensive, with North Vietnam only providing weapons and other material support. The Tet Offensive, which was known in North Vietnam as “General Offensive, General Uprising”, called for the Viet Cong to launch simultaneous attacks on many targets across South Vietnam, which would be accompanied with calls to the civilian population to launch a general uprising. North Vietnam believed that a civilian uprising in the south would succeed because of President Thieu’s unpopularity, as evidenced by the constant civil unrest and widespread criticism of government policies. In this scenario, once President Thieu was overthrown, an NLF-led communist government would succeed in power, and pressure the United States to end its involvement in South Vietnam. Faced with the threat of international condemnation, the United States would be forced to acquiesce, and withdraw its forces from Vietnam.

As part of its general strategy for the Tet Offensive, North Vietnam increased its military activity along the border region. In the last months of 1967, the North Vietnamese military launched attacks across the border, including in Song Be, Loc Ninh, and Dak To in order to lure U.S. forces away from the main urban areas. These diversionary attacks succeeded, as large numbers of U.S. troops were moved to the border areas.

In a series of clashes known as the “Border Battles”, American and South Vietnamese forces easily threw back these North Vietnamese attacks, inflicting heavy North Vietnamese casualties. However, U.S. military planners were baffled at North Vietnam’s intentions, as these attacks appeared to be a waste of soldiers and resources in the face of overwhelming American firepower.

But the North Vietnamese had succeeded in drawing away the bulk of U.S. forces from the populated centers. By the start of the Tet Offensive, half of all U.S. combat troops were in I Corps to confront what the Americans believed was an imminent major North Vietnamese invasion into the northern provinces. U.S. military intelligence had detected the build ups of Viet Cong forces in the south and the North Vietnamese in the north. But the U.S. high command, including General Westmoreland, did not believe that the Viet Cong had the capacity to mount a large offensive like that which actually occurred in the Tet Offensive.

Following some attacks one day earlier (January 30), on January 31, 1968 (which was the Vietnamese New Year or Tet, when a truce was traditionally observed), some 80,000 Viet Cong fighters, supported by some North Vietnamese Army units, launched coordinated attacks in Saigon, in 36 of the 44 provincial capitals, and in over 100 other towns across South Vietnam. In Saigon, many public and military infrastructures were hit, including the government radio station where the Viet Cong/NLF tried but failed to broadcast a pre-recorded message from Ho Chi Minh calling on the civilian population to rise up in rebellion (electric power to the radio station was cut immediately after the attack). A Viet Cong attempt to seize the U.S. Embassy in Saigon also failed.

Taken by surprise, South Vietnamese and American forces quickly assembled a defense, and then soon counterattacked. Crucially, U.S. forces that had been sent to the Cambodian border returned to Saigon just before the start of the Tet Offensive.

Viet Cong units occupied large sections of Saigon, but after bitter street-by-street, house-to-house fighting, South Vietnamese and U.S. forces soon gained the upper hand. South Vietnamese forces also mounted successful defenses in other parts of the country. In early February 1968, the Viet Cong leadership ordered a general retreat. The rebels, now suffering heavy human and material losses, withdrew from the cities and towns.

At Hue, the ancestral capital, the North Vietnamese and Viet Cong attackers, who had seized large sections of the city, were ordered to stay and defend their positions. A 28-day battle ensued, with U.S. forces, supported by naval and ground artillery and air support, advancing slowly and engaging the enemy in intense house-to-house battles. By late February 1968 when the last North Vietnamese/Viet Cong units had been driven out of Hue, some 80% of the city had been destroyed, 5,000 civilians killed, and over 100,000 people left homeless. Combat fatalities at the Battle of Hue were 700 American/South Vietnamese and 8,000 North Vietnamese/Viet Cong soldiers.

While the Tet Offensive was ongoing, General Westmoreland continued to believe that the Tet Offensive was a diversion for a major North Vietnamese attack in the north, particularly on the Khe Sanh American combat base, in preparation for a full invasion of South Vietnam’s northern provinces. Thus, he sent back only few combat troops already committed to defend the towns and cities. After the war, North Vietnamese officials have since insisted that the Tet Offensive was their main objective, and that their attack on Khe Sanh was merely a diversion to draw away U.S. forces from the Tet Offensive. Some historians also postulate that North Vietnam planned no diversion at all, but that its purpose was to launch both the Khe Sanh and Tet offensives.

Based on the second scenario, North Vietnam planned the siege at Khe Sanh as a repetition of its successful 1954 siege of the French base at Dien Bien Phu. A North Vietnamese victory at Khe Sanh would have the Americans meet the same fate as the French at Dien Bien Phu. Conversely, the U.S. military wanted Khe Sanh to be a major showdown with the North Vietnamese Army, where overwhelming American firepower would be brought to bear in battle and inflict serious losses on the enemy.

The siege on Khe Sanh began on January 21, 1968 (ten days before the Tet Offensive), when 20,000 North Vietnamese troops, after many months of logistical buildup and moving heavy artillery into the heights surrounding Khe Sanh, began a barrage of artillery, mortar, and rocket fire into the Khe Sanh combat base, which was defended by 6,000 U.S. Marines and some elite South Vietnamese troops. Another 20,000 North Vietnamese troops served as reinforcements and also cut off road access to Khe Sanh, sealing off, and thus surrounding, the base. The 77-day battle featured 1. artillery duels by both sides; 2. Khe Sanh being supplied solely by air; 3. North Vietnamese probing attacks on the Khe Sanh base; and 4. North Vietnamese assaults to dislodge U.S. Marines outposts situated on a number of nearby strategic hills.

In early April 1968, the Siege of Khe Sanh ended, with U.S. air firepower being the decisive factor. By then, American B-52 bombers had dropped some 100,000 tons of bombs (equivalent to five Hiroshima-size atomic bombs), which wreaked havoc on North Vietnamese positions. U.S. bombing also destroyed the extensive network of trenches which the North Vietnamese were building to inch ever closer to U.S. positions. The North Vietnamese planned to use the trenches as a springboard for their final assault on Khe Sanh. (The Viet Minh had used this tactic to overrun the Dien Bien Phu base in 1954.) North Vietnamese forces retreated to Laos and North Vietnam. Combat fatalities during the siege of Khe Sanh included 270 Americans, 200 South Vietnamese, and 10,000 North Vietnamese soldiers.