On August 16, 1945, Soviet forces from Manchuria continued south into the Korean Peninsula and stopped at the 38th parallel. U.S. forces soon arrived in southern Korea and advanced north, reaching the 38th parallel on September 8, 1945. Then in official ceremonies, the U.S. and Soviet commands formally accepted the Japanese surrender in their respective zones of occupation. Thereafter, the American and Soviet commands established military rule in their occupation zones.

(Taken from Korean War – Wars of the 20th Century – Twenty Wars in Asia)

As both the U.S. and Soviet governments wanted to reunify Korea, in a conference in Moscow in December 1945, the Allied Powers agreed to form a four-power (United States, Soviet Union, Britain, and Nationalist China) five-year trusteeship over Korea. During the five-year period, a U.S.-Soviet Joint Commission would work out the process of forming a Korean government. But after a series of meetings in 1946-1947, the Joint Commission failed to achieve anything. In September 1947, the U.S. government referred the Korean question to the United Nations (UN). The reasons for the U.S.-Soviet Joint Commission’s failure to agree to a mutually acceptable Korean government are three-fold and to some extent all interrelated: intense opposition by Koreans to the proposed U.S.-Soviet trusteeship; the struggle for power among the various ideology-based political factions; and most important, the emerging Cold War confrontation between the United States and the Soviet Union.

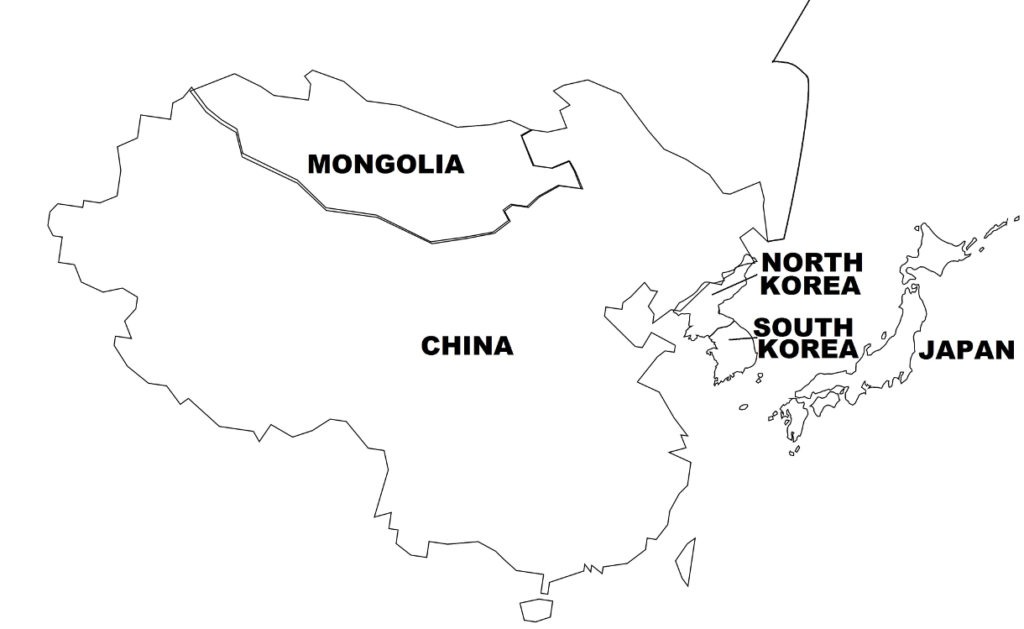

Historically, Korea for many centuries had been a politically and ethnically integrated state, although its independence often was interrupted by the invasions by its powerful neighbors, China and Japan. Because of this protracted independence, in the immediate post-World War II period, Koreans aspired for self-rule, and viewed the Allied trusteeship plan as an insult to their capacity to run their own affairs. However, at the same time, Korea’s political climate was anarchic, as different ideological persuasions, from right-wing, left-wing, communist, and near-center political groups, clashed with each other for political power. As a result of Japan’s annexation of Korea in 1910, many Korean nationalist resistance groups had emerged. Among these nationalist groups were the unrecognized “Provisional Government of the Republic of Korea” led by pro-West, U.S.-based Syngman Rhee; and a communist-allied anti-Japanese partisan militia led by Kim Il-sung. Both men would play major roles in the Korean War. At the same time, tens of thousands of Koreans took part in the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937-1945) and the Chinese Civil War, joining and fighting either for Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalist forces, or for Mao Zedong’s Chinese Red Army.

The Korean anti-Japanese resistance movement, which operated mainly out of Manchuria, was divided along ideological lines. Some groups advocated Western-style capitalist democracy, while others espoused Soviet communism. However, all were strongly anti-Japanese, and launched attacks on Japanese forces in Manchuria, China, and Korea.

On their arrival in the southern Korean zone in September 1948, U.S. forces imposed direct rule through the United States Army Military Government In Korea (USAMGIK). Earlier, members of the Korean Communist Party in Seoul (the southern capital) had sought to fill the power vacuum left by the defeated Japanese forces, and set up “local people’s committees” throughout the Korean peninsula. Then two days before U.S. forces arrived, Korean communists of the “Central People’s Committee” proclaimed the “Korean People’s Republic”.

In October 1945, under the auspices of a U.S. military agent, Syngman Rhee, the former president of the “Provisional Government of the Republic of Korea” arrived in Seoul. The USAMGIK refused to recognize the communist Korean People’s Republic, as well as the pro-West “Provisional Government”. Instead, U.S. authorities wanted to form a political coalition of moderate rightist and leftist elements. Thus, in December 1946, under U.S. sponsorship, moderate and right-wing politicians formed the South Korean Interim Legislative Assembly. However, this quasi-legislative body was opposed by the communists and other left-wing and right-wing groups.

In the wake of the U.S. authorities’ breaking up the communists’ “people’s committees” violence broke out in the southern zone during the last months of 1946. Called the Autumn Uprising, the unrest was carried out by left-aligned workers, farmers, and students, leading to many deaths through killings, violent confrontations, strikes, etc. Although in many cases, the violence resulted from non-political motives (such as targeting Japanese collaborators or settling old scores), American authorities believed that the unrest was part of a communist plot. They therefore declared martial law in the southern zone. Following the U.S. military’s crackdown on leftist activities, the communist militants went into hiding and launched an armed insurgency in the southern zone, which would play a role in the coming war.

Meanwhile in the northern zone, Soviet commanders initially worked to form a local administration under a coalition of nationalists, Marxists, and even Christian politicians. But in October 1945, Kim Il-sung, the Korean resistance leader who also was a Soviet Red Army officer, quickly became favored by Soviet authorities. In February 1946, the “Interim People’s Committee”, a transitional centralized government, was formed and led by Kim Il-sung who soon consolidated power (sidelining the nationalists and Christian leaders), and nationalized industries, and launched centrally planned economic and reconstruction programs based on the Soviet-model emphasizing heavy industry.

By 1947, the Cold War had begun: the Soviet Union tightened its hold on the socialist countries of Eastern Europe, and the United States announced a new foreign policy, the Truman Doctrine, aimed at stopping the spread of communism. The United States also implemented the Marshall Plan, an aid program for Europe’s post-World War II reconstruction, which was condemned by the Soviet Union as an American anti-communist plot aimed at dividing Europe. As a result, Europe became divided into the capitalist West and socialist East.

Reflecting these developments, in Korea by mid-1945, the United States became resigned to the likelihood that the temporary military partition of the Korean peninsula at the 38th parallel would become a permanent division along ideological grounds. In September 1947, with U.S. Congress rejecting a proposed aid package to Korea, the U.S. government turned over the Korean issue to the UN. In November 1947, the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) affirmed Korea’s sovereignty and called for elections throughout the Korean peninsula, which was to be overseen by a newly formed body, the United Nations Temporary Commission on Korea (UNTCOK).

However, the Soviet government rejected the UNGA resolution, stating that the UN had no jurisdiction over the Korean issue, and prevented UNTCOK representatives from entering the Soviet-controlled northern zone. As a result, in May 1948, elections were held only in the American-controlled southern zone, which even so, experienced widespread violence that caused some 600 deaths. Elected was the Korean National Assembly, a legislative body. Two months later (in July 1948), the Korean National Assembly ratified a new national constitution which established a presidential form of government. Syngman Rhee, whose party won the most number of legislative seats, was proclaimed as (the first) president. Then on August 15, 1948, southerners proclaimed the birth of the Republic of Korea (soon more commonly known as South Korea), ostensibly with the state’s sovereignty covering the whole Korean Peninsula.