On September 4, 1919, Mustafa Kemal Ataturk and the Turkish National Movement met at Sivas in central-eastern Turkey to formulate policy for the preservation of unity, independence, and territorial integrity of the Turkish state. The week-long assembly (September 4-11, 1919) came in the heels of the preparatory Erzurum Congress. At this time, World War I had just ended and the defeated Ottoman Empire was supine and essentially defunct, and partitioned under military occupation by the Allied Powers: French, British, Italians, and Greeks.

(Taken from Turkish War of Independence in Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 3)

As a result of this circular, Turkish nationalists met twice: at the Erzerum Congress (July-August 1991) by regional leaders of the eastern provinces, and at the Sivas Congress (September 1919) of nationalist leaders from across Anatolia. Two important decisions emerged from these meetings: the National Pact and the “Representative Committee”.

The National Pact set forth the guidelines for the Turkish state, including what constituted the “homeland of the Turkish nation”, and that the “country should be independent and free, all restrictions on political, judicial, and financial developments will be removed”. The “Representative Committee” was the precursor of a quasi-government that ultimately took shape on May 3, 1920 as the Turkish Provisional Government based in Ankara (in central Anatolia), founded and led by Kemal.

Background of the Turkish War of Independence On October 30, 1918, the Ottoman Empire ended its involvement in World War I by signing the Armistice of Mudros. During the war, the Ottoman government had fought as one of the Central Powers (in alliance with Germany, Austria-Hungary, and Bulgaria), but in 1917 and 1918, it suffered many devastating defeats. Then with the failure of the Germans’ 1918 “Spring Offensive” in Western Europe, the Anatolian heartland of the Ottoman Empire became vulnerable to an invasion, forcing Ottoman capitulation.

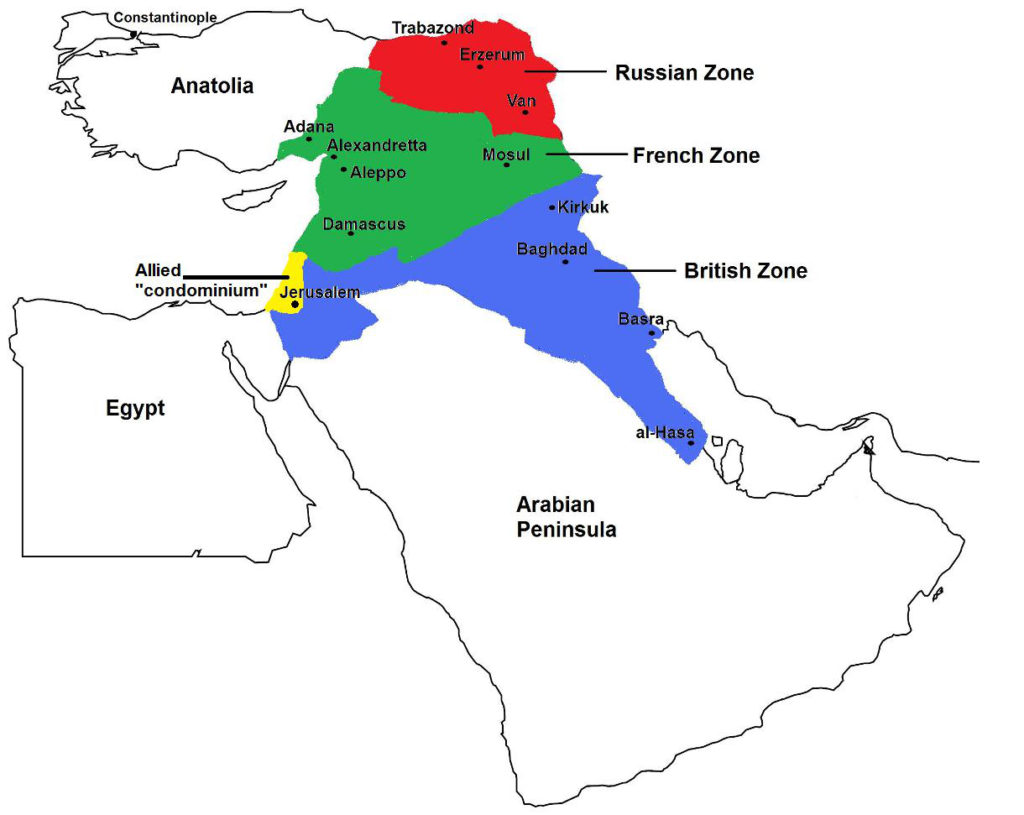

The victorious Allied Powers in Europe (Britain, France, and Italy) took steps to carry out their many secret pre-war and war-time agreements regarding the disposition of the Ottoman Empire. Another Allied power, Russia, also was a party to some of these agreements, but it had been forced out of the war in 1914 and consequently was not involved in the post-war negotiations.

As a first measure and provided by the terms of surrender, the French and British naval fleets seized control of the Turkish Straits (Dardanelles and Bosporus) on November 12-13, 1913, and landed troops in Constantinople, the Ottoman Empire’s capital.

During World War I, British forces gained possession of much of the Ottoman Empire’s colonies in the Middle East, collectively called “Greater Syria”, a vast territory covering Mesopotamia (Iraq), the Arabian Peninsula, Syria, and Palestine. When the war ended, most of the Arabian Peninsula gained independence under British sponsorship, including the Kingdom of Yemen and later the Kingdom of Nejd and Hejaz, the precursor of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia.

The most significant war-time treaty to be implemented in the Middle East was the secret Sykes-Picot Agreement, where Britain and France drew up a plan to partition between them most of the remaining Ottoman possessions, i.e. Syria and Lebanon to France, and Mesopotamia and Palestine to Britain*. As a result, following war’s end, Britain and France took control of their respective previously agreed territories in the Middle East. These annexations subsequently were legitimized as mandates by the newly formed League of Nations: i.e. the 1923 French Mandate for Syria and the Lebanon, and the 1923 British Mandate for Palestine. British control of Mesopotamia was formalized by the Anglo-Iraqi Treaty of 1922, which also established the Kingdom of Iraq.

The Allies also had drawn up a partition plan for Anatolia, the Turkish heartland of the Ottoman Empire. In this plan, Constantinople and the Turkish Straits were designated as a neutral zone under joint Allied administrations, with separate British, French, and Italian zones of occupations. Southwest Anatolia was allocated to Italy, the southeast (centered on Cilicia) to France, and a section of the northeast to Armenia. Greece, a late-comer in World War I on the Allied side, was promised the historic Hellenic region around Smyrna, as well as Eastern Thrace.

With these proposed changes, a much smaller Ottoman state would consist of central Anatolia up to the Black Sea, but no coastal outlet in the Mediterranean Sea. The Allies subsequently incorporated these stipulations in the 1920 Treaty of Sevres (Map 8), an agreement aimed at legitimizing their annexations/occupations of Ottoman territories.

The Allies wanted a breakup of the Ottomans’ centralized state, to be replaced by a decentralized federal form of government. In Constantinople, the national government led by the Sultan and Grand Vizier (Prime Minister) were resigned to these political and territorial changes. However, Turkish nationalists, representing a political and ideological movement that became powerful in the early twentieth century, opposed the Allied impositions on Anatolia, perceiving them to be a deliberate dismembering of the Turkish traditional homeland. As a result of the Allied occupation, many small Turkish nationalist armed resistance groups began to organize all across Anatolia.

Rise of the Turkish Independence Movement Under the armistice agreement, the Ottoman government was required to disarm and demobilize its armed forces. On April 30, 1919, Mustafa Kemal, a general in the Ottoman Army, was appointed as the Inspector-General of the Ottoman Ninth Army in Anatolia, with the task of demobilizing the remaining forces in the interior. Kemal was a nationalist who opposed the Allied occupation, and upon arriving in Samsun on May 19, 1919, he and other like-minded colleagues set up what became the Turkish Nationalist Movement.

Contact was made with other nationalist politicians and military officers, and alliances were formed with other nationalist organizations in Anatolia. Military units that were not yet demobilized, as well as the various armed bands and militias, were instructed to resist the occupation forces. These various nationalist groups ultimately would merge to form the nationalists’ “National Army” in the coming war. Weapons and ammunitions were stockpiled, and those previously surrendered were secretly taken back and turned over to the nationalists.

On June 21, 1919, Kemal issued the Amasya Circular, which declared among other things, that the unity and independence of the Turkish state were in danger, that the Ottoman government was incapable of defending the country, and that a national effort was needed to secure the state’s integrity. As a result of this circular, Turkish nationalists met twice: at the Erzerum Congress (July-August 1991) by regional leaders of the eastern provinces, and at the Sivas Congress (September 1919) of nationalist leaders from across Anatolia. Two important decisions emerged from these meetings: the National Pact and the “Representative Committee”.

The National Pact set forth the guidelines for the Turkish state, including what constituted the “homeland of the Turkish nation”, and that the “country should be independent and free, all restrictions on political, judicial, and financial developments will be removed”. The “Representative Committee” was the precursor of a quasi-government that ultimately took shape on May 3, 1920 as the Turkish Provisional Government based in Ankara (in central Anatolia), founded and led by Kemal.

Kemal and his Representative Committee “government” challenged the continued legitimacy of the national government, declaring that Constantinople was ruled by the Allied Powers from whom the Sultan had to be liberated. However, the Sultan condemned Kemal and the nationalists, since both the latter effectively had established a second government that was a rival to that in Constantinople.

In July 1919, Kemal received an order from the national authorities to return to Constantinople. Fearing for his safety, he remained in Ankara; consequently, he ceased all official duties with the Ottoman Army. The Ottoman government then laid down treason charges against Kemal and other nationalist leaders; tried in absentia, he was declared guilty on May 11, 1920 and sentenced to death.

Initially, British authorities played down the threat posed by the Turkish nationalists. Then when the Ottoman parliament in Constantinople declared its support for the nationalists’ National Pact and the integrity of the Turkish state, the British violently closed down the legislature, an action that inflicted many civilian casualties. The next month, the Sultan affirmed the dissolution of the Ottoman parliament.

Many parliamentarians were arrested, but many others escaped capture and fled to Ankara to join the nationalists. On April 23, 1920, a new parliament called the Grand National Assembly convened in Ankara, which elected Kemal as its first president.

British authorities soon realized that the nationalist movement threatened the Allied plans on the Ottoman Empire. From civilian volunteers and units of the Sultan’s Caliphate Army, the British organized a militia, which was tasked to defeat the nationalist forces in Anatolia. Clashes soon broke out, with the most intense taking place in June 1920 in and around Izmit, where Ottoman and British forces defeated the nationalists. Defections were widespread among the Sultan’s forces, however, forcing the British to disband the militia.

The British then considered using their own troops, but backed down knowing that the British public would oppose Britain being involved in another war, especially one coming right after World War I. The British soon found another ally to fight the war against the nationalists – Greece. On June 10, 1920, the Allies presented the Treaty of Sevres to the Sultan. The treaty was signed by the Ottoman government but was not ratified, since war already had broken out.

In the coming war, Kemal crucially gained the support of the newly established Soviet Union, particularly in the Caucasus where for centuries, the Russians and Ottomans had fought for domination. This Soviet-Turkish alliance resulted from both sides’ condemnation of the Allied intervention in their local affairs, i.e. the British and French enforcing the Treaty of Sevres on the Ottoman Empire, and the Allies’ open support for anti-Bolshevik forces in the Russian Civil War.

War Turkish nationalists fought in three fronts: in the east against Armenia, in the south against France and the French Armenian Legion, and in the west against Greece, which was backed by Britain.