(Excerpts from Battle of the Atlantic (Wars of the 20th Century – World War II in Europe))

On September 1, 1939, Germany invaded Poland; two days later, September 3, Britain and France declared war on Germany, starting World War II. On September 4, 1939, Britain imposed a naval blockade of German ports. Under the newly established British Contraband Control Service and French Blockade Ministry, the British Royal Navy and French Navy (Marine nationale) under over-all British command, imposed a blockade enforcement system where all ships passing European trade routes were required to stop for inspection at designated British ports (later expanded to include other British colonial ports along merchant routes in the Mediterranean Sea and Indian Ocean). The ships’ cargoes were examined, and items found in a broad list of designated contraband materials, which included ammunitions, explosives, and the like, but also even foodstuffs, animal feed, and clothing, were subject to seizure. The Allies intended these measures to force Germany, which was deficient in natural resources and heavily dependent on importation of food and raw materials for its people, civilian industries, and war capability, to enter into peace negotiations, thus bringing the war to an end.

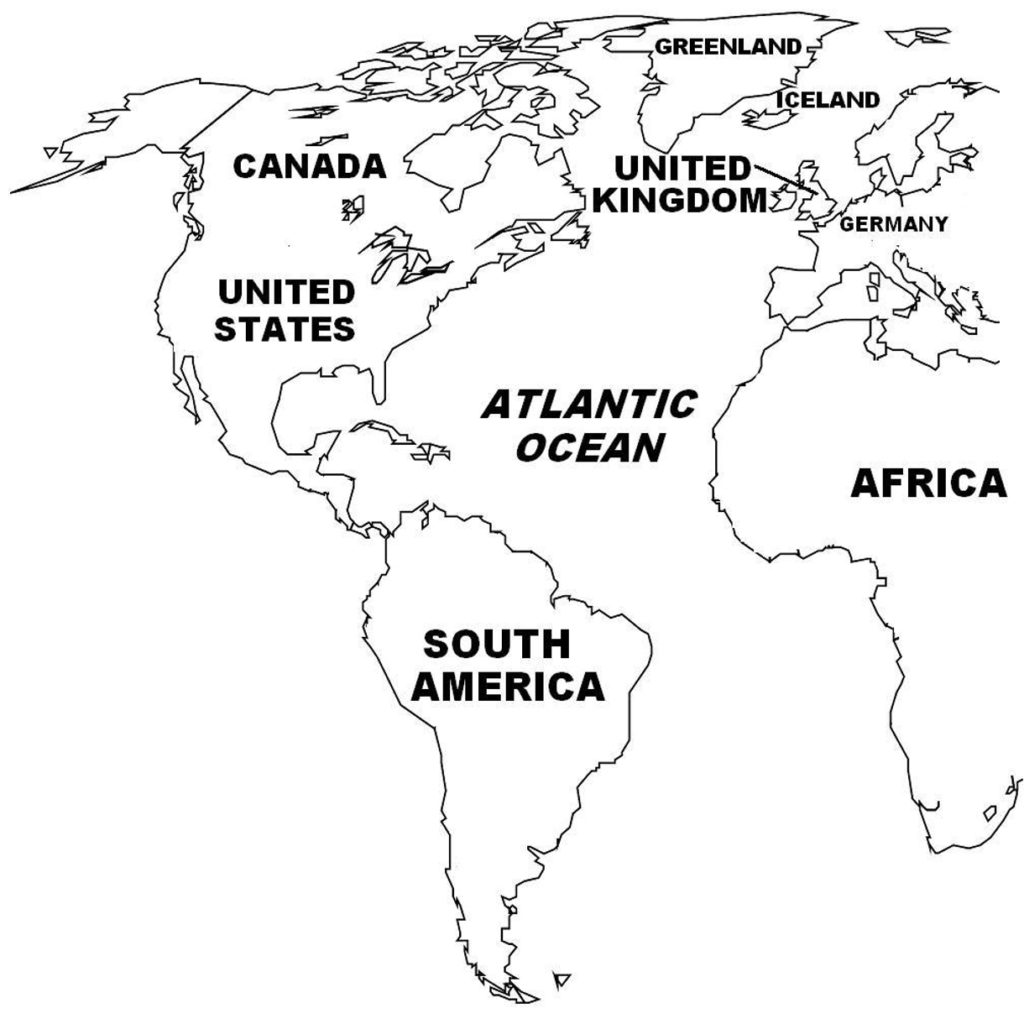

Instead, Germany imposed its own naval blockade of Britain which, as an island nation, was also heavily dependent on importation of commodities in order to survive, as well as to continue the war. Germany’s aim was to starve Britain into submission. The German Navy’s attempt to stop the flow of materials to Britain particularly from North America through the Atlantic Ocean, and the British efforts to foil the Germans constitute what is known as the Battle of the Atlantic.

By the time of the outbreak of World War II, the ambitious expansion program of the Kriegsmarine (the German Navy) under Plan Z aimed at achieving naval equality with the British Navy (the world’s largest fleet), was far from complete, and the small German fleet (by comparison) simply could not engage in open battle either the British or French fleets, the latter two having much larger navies.

Instead, early in the war, the Kriegsmarine initiated a strategy of commerce raiding, where German surface ships (battleships, cruisers, destroyers, etc.) and submarines, which were called U-boats (from the German: Unterseeboot; “undersea boat”), were sent to the Atlantic Ocean to attack Allied and neutral-nation merchant vessels bound for Britain. The Germans also used a number of armed merchant vessels, which were disguised as neutral or Allied ships but manned by German Navy personnel, for commerce raiding. As well, later in the war, long-range Luftwaffe planes, particularly the Focke-Wulf Fw 200 Condor, were used for reconnaissance and attack missions.

The German heavy cruisers Deutschland and Admiral Graf Spee, already in the Atlantic Ocean at the outbreak of war, sank several Allied merchant ships. The Allies organized several hunting groups to locate these German ships, so straining their resources as the British and French allocated three battle cruisers, three aircraft carriers, fifteen cruisers, and many auxiliary ships to scour the Atlantic. But in December 1939, the Graf Spee was caught and trapped near the River Plate (Rio de la Plata), off the South American coast, and scuttled by its crew near Montevideo, Uruguay.

Despite this success, the early hunting-group strategy proved counter-productive, as the Allies then possessed inadequate technological resources to locate U-boats, whose strength lay in avoiding detection by submerging underwater and remaining there until the danger passed. The U-boat’s other main asset was stealth, and the first naval casualty of the war, the British ocean liner, SS Athenia, was attacked and sunk by a U-boat (which it mistook for a British warship) on September 3, 1939, with 128 lives lost. Also in September 1939 and just a few days apart, two British aircraft carriers, the HMS Ark Royal and HMS Courageous, were both attacked by a U-boat, with the former narrowly being hit by torpedoes, while the latter was hit and sunk. Then in October 1939, another U-boat penetrated undetected near Scapa Flow, the main British naval base, attacking and sinking the battleship, the HMS Royal Oak.

At the start of the war, the British military was hard-pressed on how to deal with the U-boat threat. During the interwar period, prevailing naval thought and budgetary resources, both Allied and German alike, focused on surface ships, and the belief that battleships would play the dominant role in naval warfare in a future war. German U-boats had proved highly effective in World War I, causing heavy losses on merchant shipping that nearly forced Britain out of the war, before the British introduced the convoy system that turned fortunes around.

However, the British Navy’s implementing the ASDIC system (acronym for “Anti-Submarine Detection Investigation Committee”; otherwise known as SONAR), which could detect the presence of submerged submarines, appeared to have solved the U-boat threat. Naval tests showed that once detected by ASDIC, the submarine could then be destroyed by two destroyers launching depth charges overboard continuously in a long diamond pattern around the trapped vessel. The British concept was that the U-boats could operate only in coastal waters to threaten harbor shipping, as they had done in World War I, and these tests were conducted under daylight and calm weather conditions. But by the outbreak of World War II, German submarine technology had rapidly advanced, and were continuing so, that U-boats were able to reach farther out into the Atlantic Ocean, eventually ranging as far as the American eastern seacoast, and also were able to submerge to greater depths beyond the capacity of depth charges. These factors would weigh heavily in the early stages of the Battle of the Atlantic.