On September 23, 1943, Benito Mussolini founded the Italian Social Republic (Italian: Repubblica Sociale Italiana, RSI), a fascist state centered on the small town of Salo in northern Italy (hence its more commonly known name, “Republic of Salo”). RSI claimed sovereignty over most Italy, but de facto exercised authority only in the northern region, since by this time, the Allies had captured territory in southern Italy and were fighting their way north, and the defending German forces controlled the non-liberated regions. RSI had an armed force of about 150,000 troops but was totally dependent on Germany. It had been set up just after Mussolini was freed by German commandos on September 12, 1943. Mussolini had been sacked as Prime Minister and imprisoned in July 1943 after the Allies captured Sicily. The new Italian government opened secret peace talks with the Allies, leading to the Armistice of Cassibile, where Italy surrendered to the Allies. Fearing German reprisal, King Victor Emmanuel II and the new government fled to Allied-controlled southern Italy, where they set up their headquarters. In October 13, 1943, Italy declared war on Germany. But as a consequence of the armistice, German forces took over power in Italy.

The RSI existed until May 1, 1945 when German forces in Italy surrendered. Mussolini and other RSI leaders were captured by Italian partisans four days earlier, on April 27, and executed the following day.

(Taken from Mussolini and his Quest for an Italian Empire – Wars of the 20th Century – World War II in Europe)

In the midst of political and social unrest in October 1922, Benito Mussolini and his National Fascist Party came to power in Italy, with Mussolini being appointed as Prime Minister by Italy’s King Victor Emmanuel III. Mussolini, who was popularly called “Il Duce” (“The Leader”), launched major infrastructure and social programs that made him extremely popular among his people. By 1925-1927, the Fascist Party was the only legal political party, the Italian legislature had been abolished, and Mussolini wielded nearly absolute power, with his government a virtual dictatorship.

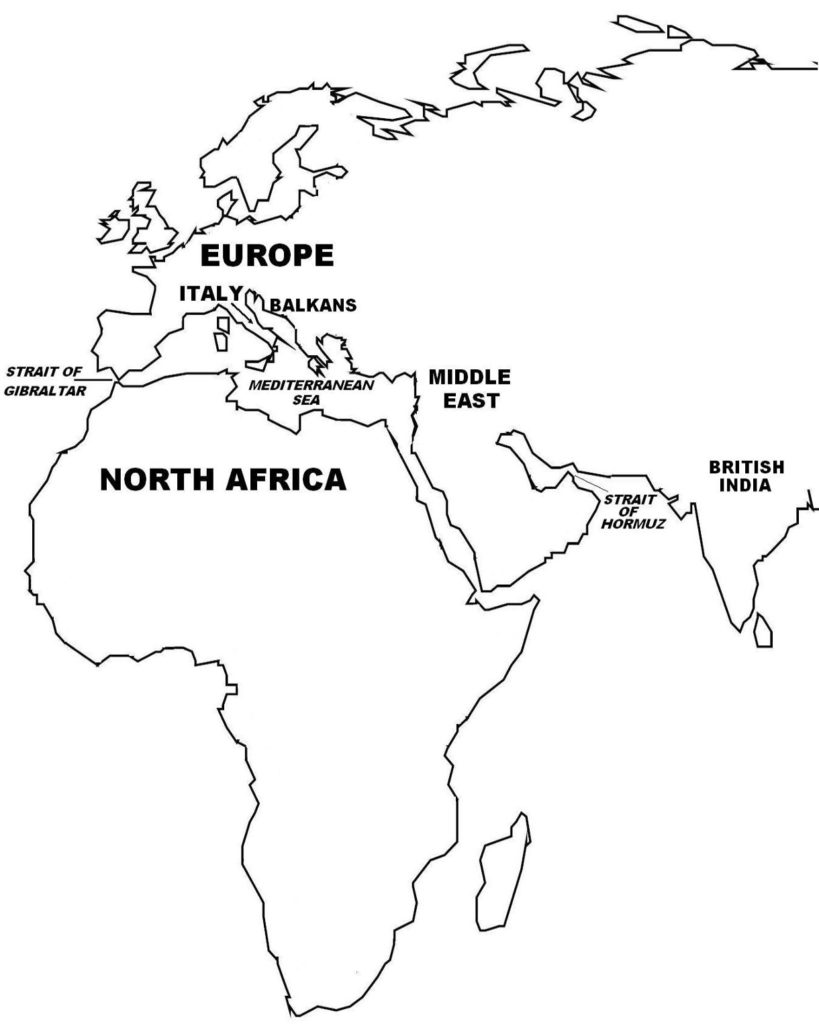

By the late 1920s through the 1930s, Mussolini pursued an overtly expansionist foreign policy. He stressed the need for Italian domination of the Mediterranean region and territorial acquisitions, including direct control of the Balkan states of Yugoslavia, Greece, Albania, Bulgaria, and Romania, and a sphere of influence in Austria and Hungary, and colonies in North Africa. Mussolini envisioned a modern Italian Empire in the likeness of the ancient Roman Empire. He explained that his empire would stretch from the “Strait of Gibraltar [western tip of the Mediterranean Sea] to the Strait of Hormuz [in modern-day Iran and the Arabian Peninsula]”. Although not openly stated, to achieve this goal, Italy would need to overcome British and French naval domination of the Mediterranean Sea.

Furthermore, in the aftermath of World War I, a strong sentiment regarding the so-called “mutilated victory” pervaded among many Italians about what they believed was their country’s unacceptably small territorial gains in the war, a sentiment that was exploited by the Fascist government. Mussolini saw his empire as fulfilling the Italian aspiration for “spazio vitale” (“vital space”), where the acquired territories would be settled by Italian colonists to ease the overpopulation in the homeland. Mussolini’s government actively promoted programs that encouraged large family sizes and higher birth rates.

Mussolini also spoke disparagingly about Italy’s geographical location in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, about how it was “imprisoned” by islands and territories controlled by other foreign powers (i.e. France and Britain), and that his new empire would include territories that would allow Italy direct access to the Atlantic Ocean in the west and the Indian Ocean in the east.

In October 1935, the Italian Army invaded independent Ethiopia, conquering the African nation by May 1936 in a brutal campaign that included the Italians using poison gas on civilians and soldiers alike. Italy then annexed Ethiopia into the newly formed Italian East Africa, which included Eritrea and Italian Somaliland. Italy also controlled Libya in North Africa as a colony.

The aftermath of Italy’s conquest of Ethiopia saw a rapprochement in Italian-Nazi German relations arising from Hitler’s support of Italy’s invasion of Ethiopia. In turn, Mussolini dropped his opposition to Germany’s annexation of Austria. Throughout the 1920s-1930s, the major European powers Britain, France, Italy, the Soviet Union and Germany, engaged in a power struggle and formed various alliances and counter-alliances among themselves, with each power hoping to gain some advantage in what was seen as an inevitable war. In this power struggle, Italy straddled the middle and believed that in a future conflict, its weight would tip the scales for victory in its chosen side.

In the end, it was Italy’s ties with Germany that prospered; both countries also shared a common political ideology. In the Spanish Civil War (July 1936-April 1939), Italy and Germany supported the rebel Nationalist forces of General Francisco Franco, who emerged victorious and took over power in Spain. In October 1936, Italy and Germany formed an alliance called the Rome-Berlin Axis. Then in 1937, Italy joined the Anti-Comintern Pact, which had been signed by Germany and Japan in November 1936. In April 1939, Italy moved one step closer to forming an empire by invading Albania, seizing control of the Balkan nation within a few days. In May 1939, Mussolini and Hitler formed a military alliance, the Pact of Steel. Two months earlier (March 1939), Germany completed the dissolution and partial annexation of Czechoslovakia. The alliance between Germany and Italy, together with Japan, reached its height in September 1940, with the signing of the Tripartite Pact, and these countries came to be known as the Axis Powers.

On September 1, 1939 World War II broke out when Germany attacked Poland, which immediately embroiled the major Western powers, France and Britain, and by September 16 the Soviet Union as well (as a result of a non-aggression pact with Germany, but not as an enemy of France and Britain). Italy did not enter the war as yet, since despite Mussolini’s frequent blustering of having military strength capable of taking on the other great powers, Italy in fact was unprepared for a major European war.

Italy was still mainly an agricultural society, and industrial production for war-convertible commodities amounted to just 15% that of Britain and France. As well, Italian capacity for vital items such as coal, crude oil, iron ore, and steel lagged far behind the other western powers. In military capability, Italian tanks, artillery, and aircraft were inferior and mostly obsolete by the start of World War II, although the large Italian Navy was ably powerful and possessed several modern battleships. Cognizant of these deficiencies, Mussolini placed great efforts to building up Italian military strength, and by 1939, some 40% of the national budget was allocated to the armed forces. Even so, Italian military planners had projected that its forces would not be fully prepared for war until 1943, and therefore the sudden start of World War II came as a shock to Mussolini and the Italian High Command.

In April-June 1940, Germany achieved a succession of overwhelming conquests of Denmark, Norway, the Netherlands, Belgium, Luxembourg, and France. As France verged on defeat and with Britain isolated and facing possible invasion, Mussolini decided that the war was over. In an unabashed display of opportunism, on June 10, 1940, he declared war on France and Britain, bringing Italy into World War II on the side of Germany, and stating, “I only need a few thousand dead so that I can sit at the peace conference as a man who has fought”.