On January 12, 1958, Saharan Liberation Army (SLA) revolutionaries attacked El-Aaiún, the capital of Spanish Sahara, but were repulsed. The 13th Banderas, a battalion of the Spanish Legion, pursued the retreating revolutionaries from the city but was caught in an ambush at Edchera. Some of the war’s most intense fighting followed, with the Spanish fending off repeated enemy attacks and more units on both sides joining the battle. Ultimately, the revolutionaries withdrew into the night after sustaining some 240 killed. Spanish losses also were heavy, officially placed at 37 dead and 50 wounded, but perhaps higher and even as many as the number of enemy casualties.

(Taken from Ifni War – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 4)

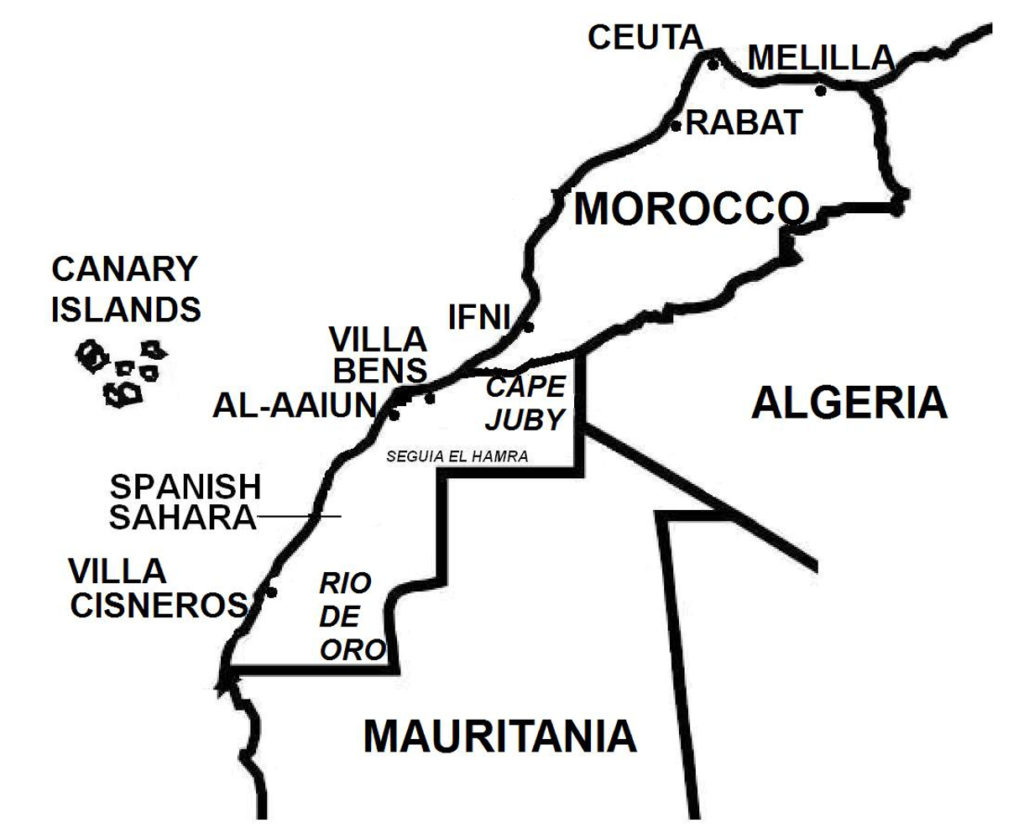

Background In 1956, Morocco gained full independence after France and Spain ended their 44-year protectorate and returned political and territorial control to Mohammed V, the Moroccan Sultan. A period of rising tensions and violence had preceded Morocco’s independence which nearly broke out into open hostilities. While France fully ended its protectorate, Spain only did so with its northern zone, retaining control of the southern zone (consisting of Cape Juby and the interior area called the Tarfaya Strip). At Morocco’s independence, apart from Morocco’s southern zone, Spain held a number of other territories in North Africa that the Spanish government viewed as integral parts of Spain (i.e. they were not colonies or protectorates); these included Ceuta and Melilla which Spain had controlled since the 1500s; Plazas de soberanía (English: Places of sovereignty), a motley of tiny islands and small areas bordering the Moroccan Mediterranean coastline; and Spanish Sahara, a vast territory half the size of mainland Spain that the Spanish government had gained in 1884 as a result of the Berlin Conference during the period known as the “Scramble for Africa”, where European powers wrangled for their “share” of Africa.

Spain declared having historical ties, by way of the Spanish Empire, to the Ifni region (traced incorrectly to Santa Cruz de la Mar Pequeña, a 15th century Spanish settlement which was actually located further south of Ifni), Villa Cisneros, founded in 1502 and located in Spanish Sahara, and the Plazas de soberanía. In 1946, Spain merged the regions of Ifni, Cape Juby and Tarfaya Strip (southern zone of the Spanish protectorate), and Spanish Sahara into a single administrative unit called Spanish West Africa (Figure 13).

The Ifni region, which had at its capital the coastal city of Sidi Ifni, would become the focal point as well as lend its name to the coming war. After its defeat in the Spanish-Moroccan War in April 1860, Morocco ceded Ifni to Spain as a result of the Treaty of Tangiers.

Shortly after Morocco gained its independence, an ultra-nationalist movement, the Istiqlal Party led by Allal Al Fassi, advocated “Greater Morocco”, a political ideology that desired to integrate all territories that had historical ties to the Moroccan Sultanate with the modern Moroccan state. As envisioned, Greater Morocco would consist of, apart from present-day Morocco itself, western Algeria, Mauritania, and northwest Mali – and all Spanish possessions in North Africa.

Officially, the Moroccan government did not subscribe to or espouse “Greater Morocco”, but did not suppress and even tacitly supported irredentist advocates of this ideology. As a result, the Moroccan Army did not actively participate in the coming war; instead, the Moroccan Army of Liberation (MAL), which was an assortment of several Moroccan militias that had organized and risen up against the French protectorate, carried out the war against the Spanish (and French).

Shortly after Morocco gained its independence, civil unrest broke out in Ifni, which included anti-Spanish protest demonstrations and violence targeting police and security forces. Infiltrators belonging to MAL later began supporting these activities. The unrest prompted the central government in mainland Spain, led by General Francisco Franco, to send Spanish troops, including units of the Spanish Legion, to Spanish West Africa, whose security units until then consisted mostly of personnel recruited from the local population.

Meanwhile, MAL militias, comprising some 4,000–5,000 Moukhahidine (“freedom fighters”) and led by Ben Hamou, a Moroccan former mercenary officer of the French Foreign Legion, had deployed near southern Moroccan and Spanish Sahara, and soon were joined by Sahrawi Berber and Arab fighters; at their peak, some 30,000 revolutionaries would take part in the conflict.