An Israeli armored division in the Sinai advanced to the Suez Canal in order to establish a crossing and to protect the Israeli forces in Egypt from being cut off. Egyptian tank units met the Israeli advance. In an intense two-day encounter that saw nighttime tank battles at very close range and cost hundreds of soldier deaths and 180 tanks destroyed, Israeli forces succeeded in gaining a toehold on the eastern bank of the Suez Canal. On October 18, 1973, the Israelis laid down a roller bridge to the other side; soon, infantry and armored units were crossing into Egypt.

The objectives of the Israeli offensives into Egypt were for one armored division to move north and capture the city of Ismailia to cut off Egypt’s Second Army across the Suez Canal, and for another armored division, flanked by an auxiliary third armored unit, to head south and take the city of Suez to isolate the Egypt’s Third Army across the channel.

The Israeli crossings caught the Egyptians off-guard. Consequently, the Israelis made rapid advance, beating back the Egyptian forces in several battles and penetrating 20 miles into Egypt along a 25-mile axis. In their drive toward Ismailia, the Israelis overran the Egyptian lines of defense in a series of armored battles. By October 21, they were within sight of the city. Egyptian resistance soon intensified, and an Israeli attempt to encircle the city was foiled. The Israeli offensive finally was stopped ten kilometers off Ismailia. The Israelis had failed to cut off the Egyptian Second Army whose supply and communication lines to Ismailia remained secure.

Meanwhile, the Israeli advance to the city of Suez saw many tactical, disorganized battles where the Egyptian forces were thrown back. On October 22, the UN imposed a ceasefire, which was not respected as fighting continued, with the Egyptians and Israelis accusing each other of continuing hostilities. The Israelis advanced further south, widening their areas of control and cutting off the Egyptian Third Army in the Sinai. The Israelis gained control of sections of Suez City; on October 25, an armored unit captured Adabiya, the Israelis’ farthest southward advance.

(Taken from Yom Kippur War – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 2)

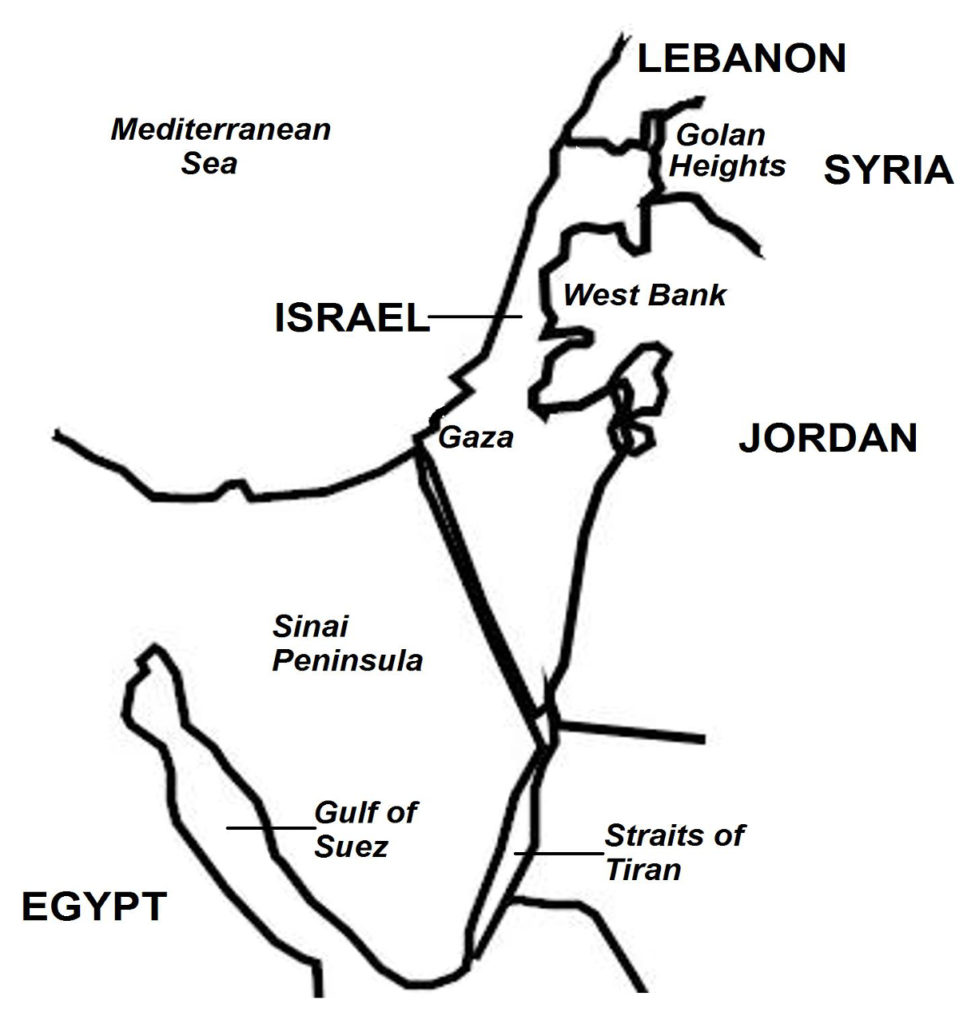

Background of the Yom Kippur War With its decisive victory in the Six-Day War (previous article) in June 1967, Israel gained control of the Sinai Peninsula and Gaza Strip from Egypt, the Golan Heights from Syria, and the West Bank from Jordan. The Sinai Peninsula and Golan Heights were integral territories of Egypt and Syria, respectively, and both countries were determined to take them back. In September 1967, Egypt and Syria, together with other Arab countries, issued the Khartoum Declaration of the “Three No’s”, that is, no peace, recognition, and negotiations with Israel, which meant that only armed force would be used to win back the lost lands.

Shortly after the Six-Day War ended, Israel offered to return the Sinai Peninsula and Golan Heights in exchange for a peace agreement, but the plan apparently was not received by Egypt and Syria. In October 1967, Israel withdrew the offer.

In the ensuing years after the Six-Day War, Egypt carried out numerous small attacks against Israeli military and government targets in the Sinai. In what is now known as the “War of Attrition”, Egypt was determined to exact a heavy economic and human toll and force Israel to withdraw from the Sinai. By way of retaliation, Israeli forces also launched attacks into Egypt. Armed incidents also took place across Israel’s borders with Syria, Jordan, and Lebanon. Then, as the United States, which backed Israel, and the Soviet Union, which supported the Arab countries, increasingly became involved, the two superpowers prevailed upon Israel and Egypt to agree to a ceasefire in August 1970.

In September 1970, Gamal Abdel Nasser, Egypt’s hard-line president, passed away. Succeeding as Egypt’s head of state was Vice-President Anwar Sadat, who began a dramatic shift in foreign policy toward Israel. Whereas the former regime was staunchly hostile to Israel, President Sadat wanted a diplomatic solution to the Egyptian-Israeli conflict. In secret meetings with U.S. government officials and a United Nations (UN) representative, President Sadat offered a proposal that in exchange for Israel’s return of the Sinai to Egypt, the Egyptian government would sign a peace treaty with Israel and recognize the Jewish state.

However, the Israeli government of Prime Minister Golda Meir refused to negotiate. President Sadat, therefore, decided to use military force. He knew, however, that his armed forces were incapable of dislodging the Israelis from the Sinai. He decided that an Egyptian military victory on the battlefield, however limited, would compel Israel to see the need for negotiations. Egypt began preparations for war. Large amounts of modern weapons were purchased from the Soviet Union. Egypt restructured its large, but ineffective, armed forces into a competent fighting force.

In order to conceal its war plans, Egypt carried out a number of ruses. The Egyptian Army constantly conducted military exercises along the western bank of the Suez Canal, which soon were taken lightly by the Israelis. Egypt’s persistent war rhetoric eventually was regarded by the Israelis as mere bluff. Through press releases, Egypt underreported the true strength of its armed forces. The government also announced maintenance and spare parts problems with its war equipment and the lack of trained personnel to operate sophisticated military hardware. Furthermore, when President Sadat expelled 20,000 Soviet advisers from Egypt in July 1972, Israel believed that the Egyptian Army’s military capability was weakened seriously. In fact, thousands of Soviet personnel remained in Egypt and Soviet arms shipments continued to arrive. Egyptian military planners worked closely and secretly with their Syrian counterparts to devise a simultaneous two-front attack on Israel. Consequently, Syria also secretly mobilized for war.

Israel’s intelligence agencies learned many details of the invasion plan, even the date of the attack itself, October 6. Israel detected the movements of large numbers of Egyptian and Syrian troops, armor, and – in the Suez Canal– bridging equipment. On October 6, a few hours before Egypt and Syria attacked, the Israeli government called for a mobilization of 120,000 soldiers and the entire Israeli Air Force. However, many top Israeli officials continued to believe that Egypt and Syria were incapable of starting a war and that the military movements were just another army exercise. Israeli officials decided against carrying out a pre-emptive air strike (as Israel had done in the Six-Day War) to avoid being seen as the aggressor. Egypt and Syria chose to attack on Yom Kippur (which fell on October 6 in 1973), the holiest day of the Jewish calendar, when most Israeli soldiers were on leave.