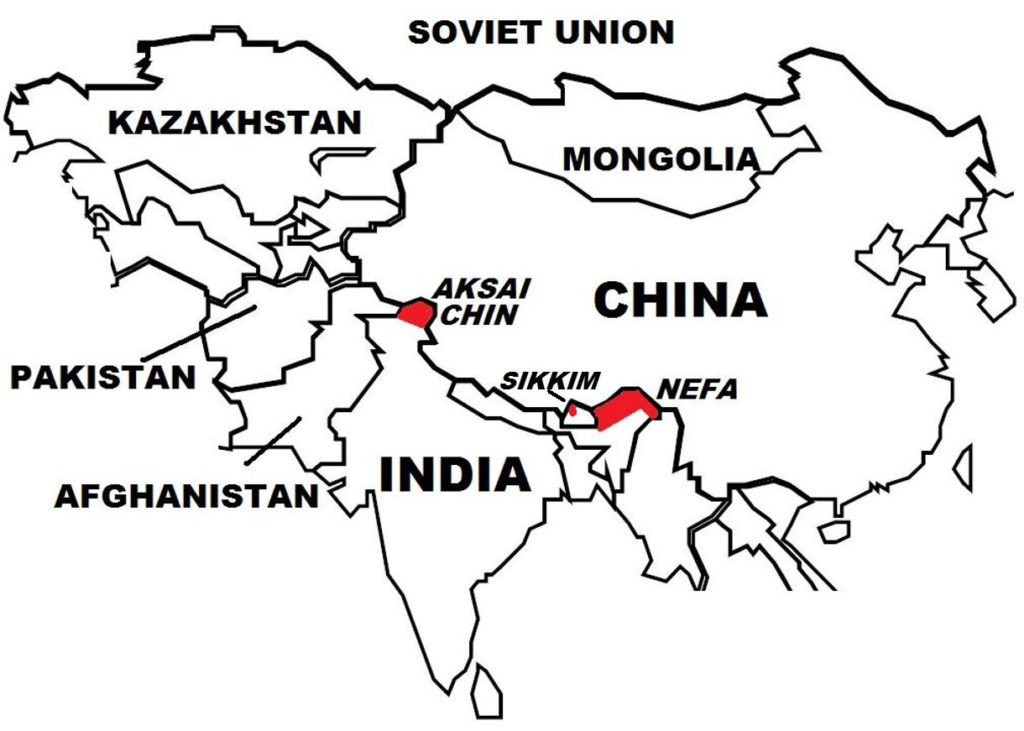

Fighting broke out on October 20, 1962, with Chinese forces launching offensives in two main sectors: in the eastern sector (North-East Frontier Agency; NEFA) north of the McMahon Line, and in the western sector in Aksai Chin. Some fighting also occurred in the Nathu La Pass, Sikkim near the China-India border. The Chinese government called the operation a “self-defensive counterattack”, implying that India had started the war by crossing north of the McMahon Line.

(Taken from Sino-Indian War – Wars of the 20th Century – Twenty Wars in Asia)

Background In the 19th century, the British and Russian Empires were locked in a political and territorial rivalry known as the Great Game, where the two powers sought to control and dominate Central Asia. The Russians advanced southward into territories that ultimately would form the present-day countries of Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan, while the British advanced northward across the Indian subcontinent. By the mid-1800s, Britain had established full control over territories of British India and the Princely States (present-day India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh). Just as it did with the Russians regarding British territories in northwest India, the British government sought to establish its territorial limits in the east with the other great regional power, China. British authorities particularly wanted to delineate British India’s boundaries in Kashmir in the north with China’s Xinjiang Province, as well as British India’s borders in the east with Tibet (a semi-autonomous state under Chinese suzerainty), thereby establishing a common British India-China border across the towering Himalaya Mountains.

In 1865, the Survey of India published a boundary for Kashmir that included the 37,000 square-kilometer Aksai Chin region (Figure 43), a barren, uninhabited high-altitude (22,000 feet) desert containing salt and soda flats. However, this delineation, called the Johnson Line (named after William Johnson, a British surveyor), was rejected by the British government.

In 1893, a Chinese official in Kashgar proposed to the British that the Laktsang Range serve as the British India-China border, with the Lingzi Tang Plains to its south to become part of Kashmir and Aksai Chin to its north to become part of China. The proposal found favor with the British, who in 1899, drew the Macartney-MacDonald Line (named after George Macartney, the British consul-general in Kashgar and Claude MacDonald, a British diplomat), which was presented to the Chinese government. The latter did not respond, which the British took to mean that the Chinese agreed with the Line. Thereafter, up until about 1908, British maps of India featured the Macartney-MacDonald Line (Figure 44) as the China-India border. However, by the 1920s, the British published new maps using the Johnson Line as the Kashmir-Xinjiang border.

Similarly, British authorities took steps to establish British India’s boundaries with Tibet and China. For this purpose, in 1913-1914, in a series of negotiations held in Simla (present-day Shimla in northern India), representatives from China, Tibet, and British India agreed on the territorial limits between “Outer Tibet” and British India. Outer Tibet was to be formed as an autonomous Tibetan polity under Chinese suzerainty. However, the Chinese delegate objected to the proposed border between “Outer Tibet” and “Inner Tibet”, and walked out of the conference. Tibetan and British representatives continued with the conference, leading to the Simla Accord (1914) which established the McMahon Line (named after Henry McMahon, the Foreign Secretary of British India). In particular, some 80,000 square kilometers became part of British India, which later was administered as the North-East Frontier Agency (NEFA). The Tawang area, located near the Bhutan-Tibet-India junction, also was ceded to British India and would become a major battleground in the Sino-Indian War.

The Chinese government rejected the Simla Accord, stating that Tibet, as a political subordinate of China, could not enter into treaties with foreign governments. The British also initially were averse to implementing the Simla Accord, as it ran contrary to the 1907 Anglo-Russian Convention which recognized China’s suzerainty over Tibet. But with Russia and Britain agreeing to void the 1907 Convention, the British established the McMahon Line (Figure 44) as the Tibet-India border. By the 1930s, the British government had begun to use the McMahon Line in its British Indian maps.

In August 1947, British rule in India ended with the partition of British India into the independent countries of India and Pakistan. Meanwhile, for much of the first half of the 20th century, China convulsed in a multitude of conflicts: the Revolution of 1911 which ended 2,000 years of imperial rule; the fracturing of China during the warlord era (1916-1928); the Japanese invasion and occupation of Manchuria in 1931, and then of other parts of China in 1937-1945; and the Chinese Civil War (1927-1949) between Communist and Nationalist forces. By 1949, communist forces had prevailed in the civil war and in October of that year, Mao Zedong, Chairman of the Communist Party of China, proclaimed the formation of the People’s Republic of China (PRC).

The government of Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru was among the first in the international community to recognize the PRC, and in the years that followed, sought to cultivate strong Indian-Chinese relations.

In the early 1950s, a series of diplomatic and cultural exchanges between India and China led in April 1954 to an eight-year agreement called the Panchsheel Treaty (Sanskrit, panch, meaning five, and sheel, meaning virtues), otherwise known as the Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence, which was meant to form the basis for good relations between India and China. The Panscheel five principles are: mutual respect for each other’s territorial integrity and sovereignty; mutual non-aggression; mutual non-interference in each other’s internal affairs; equality and cooperation for mutual benefit; and peaceful co-existence. The slogan “Indians and Chinese are brothers” (Hindi: Hindi China bhai bhai) was popular and Prime Minister Nehru advocated a Sino-Indian “Asian Axis” to serve as a counter-balance to the American-Soviet Cold War rivalry.

However, the poorly defined India-China border would overcome these attempts to establish warm bilateral relations. From the outset, India and China claimed ownership over Aksai Chin and NEFA. India released maps that essentially duplicated the British-era maps which showed both areas as part of India. China likewise claimed sovereignty over these areas, but also stated that as it had not signed any border treaties with the former British Indian government, the India-China border must be resolved through new negotiations.

Two events caused Sino-Indian relations to deteriorate further. First, in the 1950s, China built a road through Aksai Chin that linked Xinjiang and Tibet. Second, in 1959, in the aftermath of a failed Tibetan uprising against the Chinese occupation forces in Tibet, the Indian government provided refuge in India for the Dalai Lama, Tibet’s political and spiritual leader. Earlier in 1950, China had invaded and annexed Tibet. The Indian government had hoped that Tibet would remain an independent state (and a buffer zone between India and China, as it had been in the colonial era), but in the early 1950s period of friendly Sino-Indian relations, India did not oppose Chinese military action in Tibet.