On November 8, 1940, Greek forces repulsed an Italian offensive at the Battle of Elaia-Kalamas during the Greco-Italian War. The Italians launched their invasion of Greece on October 28, 1940. At the coastal flank of the Epirus sector, the Greek main defensive line was located at Elaia-Kalamas, some 30 km south of the Greek-Albanian border. On November 2, Italian forces launched air and artillery strikes on Greek positions, and by November 5, were able to establish a bridgehead over the Kalamas River. However, Greek defenses held despite repeated attempts to break through with infantry and light and medium tanks. The Italian offensive stalled as much as by the tenacity of the defenders and minefields as by the harsh hilly, rugged terrain and muddy ground caused by heavy rains.

(Taken from Greco-Italian War – Wars of the 20th Century – World War II in Europe)

On October 28, 1940, Italian forces in Albania, which were massed at the Greek-Albanian border, opened their offensive along a 90-mile (150 km) front in two sectors: in Epirus, which comprised the main attacking force; and in western Macedonia, where the Italian forces were to hold their ground and remain inside Albania. A third force was assigned to guard the Albania-Yugoslavia frontier. The Italian offensive was launched in the fall season, and would be expected to face extremely difficult weather conditions in high-altitude mountain terrain, and be subject to snow, sleet, icy rain, fog, and heavy cloud cover. As it turned out, the Italians were supplied only with summer clothing, and so were unprepared for these conditions. The Italians also had planned to seize Corfu, which was cancelled due to bad weather.

At the Epirus sector, the Italians attacked along three points: at the coast for Konispol and proceeding to the main targets of Igoumenitsa and Preveza; at the center of Kalpaki; and in the Pindus Mountains separating Epirus and western Macedonia, towards Metsovo. The coastal advance made some progress, gaining 40 miles (60 km) in the first few days without meeting serious resistance and seizing Igoumenitsa and Margariti. The Italians soon were stalled at the Kalamas River, which was swollen and raging from recent heavy rains.

Background In April 1939, Italian forces invaded Albania (previous article) in what Italian leader Benito Mussolini hoped would be the first step to founding an Italian Empire (in the style of the ancient Roman Empire) in southern Europe, which would be added to the colonies that he already possessed in Africa (Italian East Africa and Libya).

In September 1939, World War II broke out in Europe when Germany attacked Poland, prompting Britain and France to declare war on Germany. After an eight-month period of combat inactivity in Europe (called the “Phoney War”), in April 1940, Germany launched the invasions to the north and west, which ended in the defeat of France on June 25, 1940. In July 1940, Hitler set his sights on Britain, with the Luftwaffe (German Air Force) launching attacks (lasting until May 1941) aimed at eliminating the last impediment to his full domination of Western Europe.

To Mussolini, France’s defeat and Britain’s desperate position seemed the perfect time to advance his ambitions in southern Europe. Just as France was verging on defeat from the German onslaught, on June 10, 1940, in a brazen act of opportunism[1], Mussolini entered World War II on Germany’s side by declaring war on France and Britain, and sending Italian forces that attacked France through the Italian-French border. Then with Britain grimly fighting for its own survival from the German air attacks (Battle of Britain, separate article), Mussolini set his sights on British possessions in Africa, with Italian forces seizing British Somaliland in August 1940, and advancing into Egypt from Libya in September 1940.

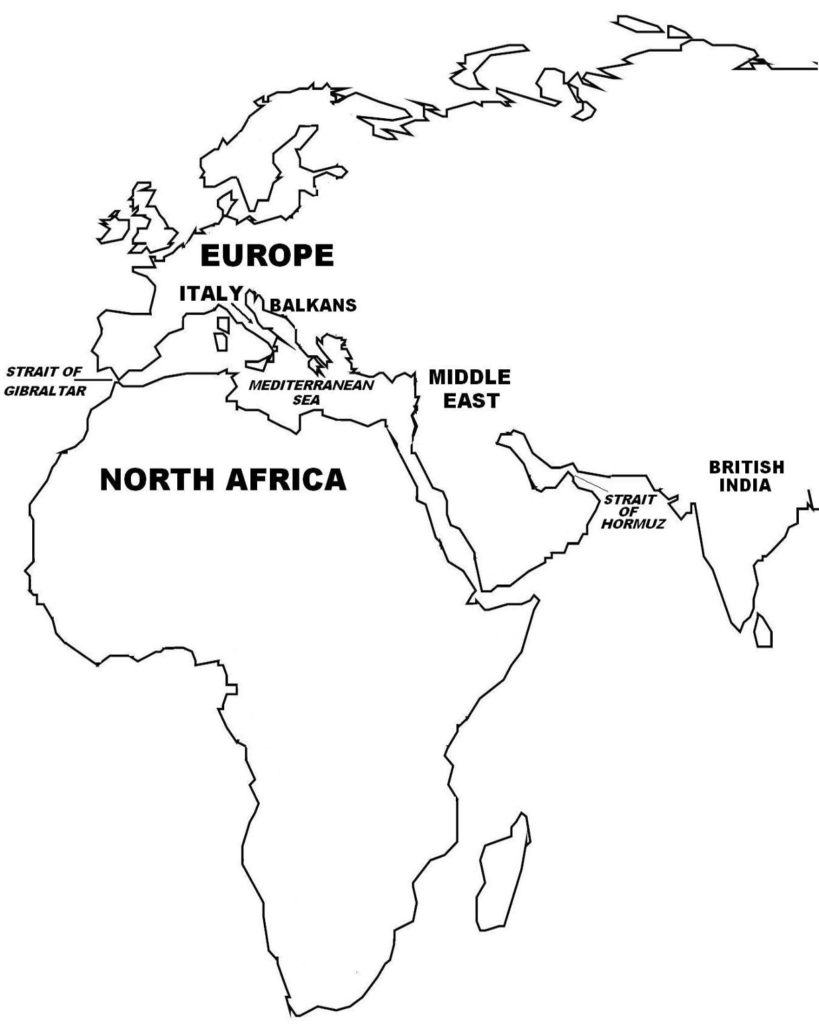

At the same time, Mussolini was ready to build an Italian Empire, with his attention focused on the Balkans which he saw as falling inside the Italian sphere of influence. He also longed to gain mastery of the Mediterranean Sea in the Mare Nostrum (“Our Sea”) concept, and turn it into an “Italian lake”. He chafed at Italy’s geographical location in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, likening it to being shut in and imprisoned by the British and French, who controlled much of the surrounding regions and possessed more powerful navies. Mussolini was determined to expand his own navy and gain dominance over southern Europe and northern Africa, and ultimately build an empire that would stretch from the Strait of Gibraltar at the western tip of the Mediterranean Sea to the Strait of Hormuz near the Persian Gulf.

Meanwhile, Greece had become alarmed by the Italian invasion of Albania. Greek Prime Minister Ioannis Metaxas, who ironically held fascist views and was pro-German, turned to Britain for assistance. The British Royal Navy, which had bases in many parts of the Mediterranean, including Gibraltar, Malta, Cyprus, Egypt, and Palestine, then made security stops in Crete and other Greek islands.

Italian-Greek relations, which were strained since the late 1920s by Mussolini’s expansionist agenda, deteriorated further. In 1940, Italy initiated an anti-Greek propaganda campaign, which included the demand that the Greek region of Epirus must be ceded to Albania, since it contained a large ethnic Albanian population. The Epirus claim was popular among Albanians, who offered their support for Mussolini’s ambitions on Greece. Mussolini accused Greece of being a British puppet, citing the British naval presence in Greek ports and offshore waters. In reality, he was alarmed that the British Navy lurking nearby posed a direct threat to Italy and hindered his plans to establish full control of the Adriatic and Ionian Seas.

Italy then launched armed provocations against Greece, which included several incidents in July-August 1940, where Italian planes attacked Greek vessels at Kissamos, Gulf of Corinth, Nafpaktos, and Aegina. On August 15, 1940, an undetected Italian submarine sank the Greek light cruiser Elli. Greek authorities found evidence that pointed to Italian responsibility for the Elli sinking, but Prime Minister Metaxas did not take any retaliatory action, as he wanted to avoid war with Italy.

Also in August 1940, Mussolini gave secret orders to his military high command to start preparations for an invasion of Greece. But in a meeting with Hitler, Mussolini was prevailed upon by the German leader to suspend the invasion in favor of the Italian Army concentrating on defeating the British in North Africa. Hitler was concerned that an Italian incursion in the Balkans would worsen the perennial state of ethnic tensions in that region and perhaps prompt other major powers, such as the Soviet Union or Britain, to intervene there. The Romanian oil fields at Ploiesti, which were extremely vital to Germany, could then be threatened. In August 1940, unbeknown to Mussolini, Hitler had secretly instructed the Germany military high command to draw up plans for his greatest project of all, the conquest of the Soviet Union. And for this monumental undertaking, Hitler wanted no distractions, including one in the Balkans. In the fall of 1940, Mussolini deferred his attack on Greece, and issued an order to demobilize 600,000 Italian troops.

Then on October 7, 1940, Hitler deployed German troops in Romania at the request of the new pro-Nazi government led by Prime Minister Ion Antonescu. Mussolini, upon being informed by Germany four days later, was livid, as he believed that Romania fell inside his sphere of influence. More disconcerting for Mussolini was that Hitler had again initiated a major action without first notifying him. Hitler had acted alone in his conquests of Poland, Denmark, Norway, France, and the Low Countries, and had given notice to the Italians only after the fact. Mussolini was determined that Hitler’s latest stunt would be reciprocated with his own move against Greece. Mussolini stated, “Hitler faces me with a fait accompli. This time I am going to pay him back in his own coin. He will find out from the papers that I have occupied Greece. In this way, the equilibrium will be re-established.”

On October 13, 1940 and succeeding days, Mussolini finalized with his top military commanders the immediate implementation of the invasion plan for Greece, codenamed “Contingency G”, with Italian forces setting out from Albania. A modification was made, where an initial force of six Italian divisions would attack the Epirus region, to be followed by the arrival of more Italian troops. The combined forces would advance to Athens and beyond, and capture the whole of Greece. The modified plan was opposed by General Pietro Badoglio, the Italian Chief of Staff, who insisted that the original plan be carried out: a full-scale twenty-division invasion of Greece with Athens as the immediate objective. Other factors cited by military officers who were opposed to immediate invasion were the need for more preparation time, the recent demobilization of 600,000 troops, and the inadequacy of Albanian ports to meet the expected large volume of men and war supplies that would be brought in from Italy.

But Mussolini would not be dissuaded. His decision to invade was greatly influenced by three officials: Foreign Minister Count Galeazzo Ciano (who was also Mussolini’s son-in-law), who stated that most Greeks detested their government and would not resist an Italian invasion; the Italian Governor-General of Albania Francesco Jacomoni, who told Mussolini that Albanians would support an Italian invasion in return for Epirus being annexed to Albania; and the commander of Italian forces in Albania General Sebastiano Prasca, who assured Mussolini that Italian troops in Albania were sufficient to capture Epirus within two weeks. These three men were motivated by the potential rewards to their careers that an Italian victory would have; for example, General Prasca, like most Italian officers, coveted being conferred the rank of “Field Marshall”. Mussolini’s order for the invasion had the following objectives, “Offensive in Epirus, observation and pressure on Salonika, and in a second phase, march on Athens”.

On October 18, 1940, Mussolini asked King Boris II of Bulgaria to participate in a joint attack on Greece, but the monarch declined, since under

the Balkan Pact of 1934, other Balkan countries would intervene for Greece in a Bulgarian-Greek

war. Deciding that its border with Bulgaria was secure from attack, the Greek

government transferred half of its forces defending the Bulgarian border to Albania;

as well, all Greek reserves were deployed to the Albanian front. With these moves, by the start of the war,

Greek forces in Albania

outnumbered the attacking Italian Army. Greece

also fortified its Albanian frontier.

And because of Mussolini’s increased rhetoric and threats of attack, by

the time of the invasion, the Italians had lost the element of surprise.

[1] Mussolini had stated just five days earlier, on June 5, 1940, “I only need a few thousand dead so that I can sit at the peace conference as a man who has fought”.