Upon his ascent to the throne on February 28, 1919, Emir Amanullah I declared Afghanistan’s independence, doing away with his father’s policy of trying to gain the country’s sovereignty through diplomatic means. The declaration of independence was immensely popular among Afghans, as nationalist sentiments ran high. Emir Amanullah therefore was able to consolidate his hold on power, even as some sectors opposed his leadership. Emir Amanullah provoked the British by inciting an uprising of the tribal people in Peshawar, British India. Using the uprising as a diversion, he sent his forces across the Afghan-British Indian border to capture the town of Bagh.

(Taken from Anglo-Afghan War of 1919 – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 1)

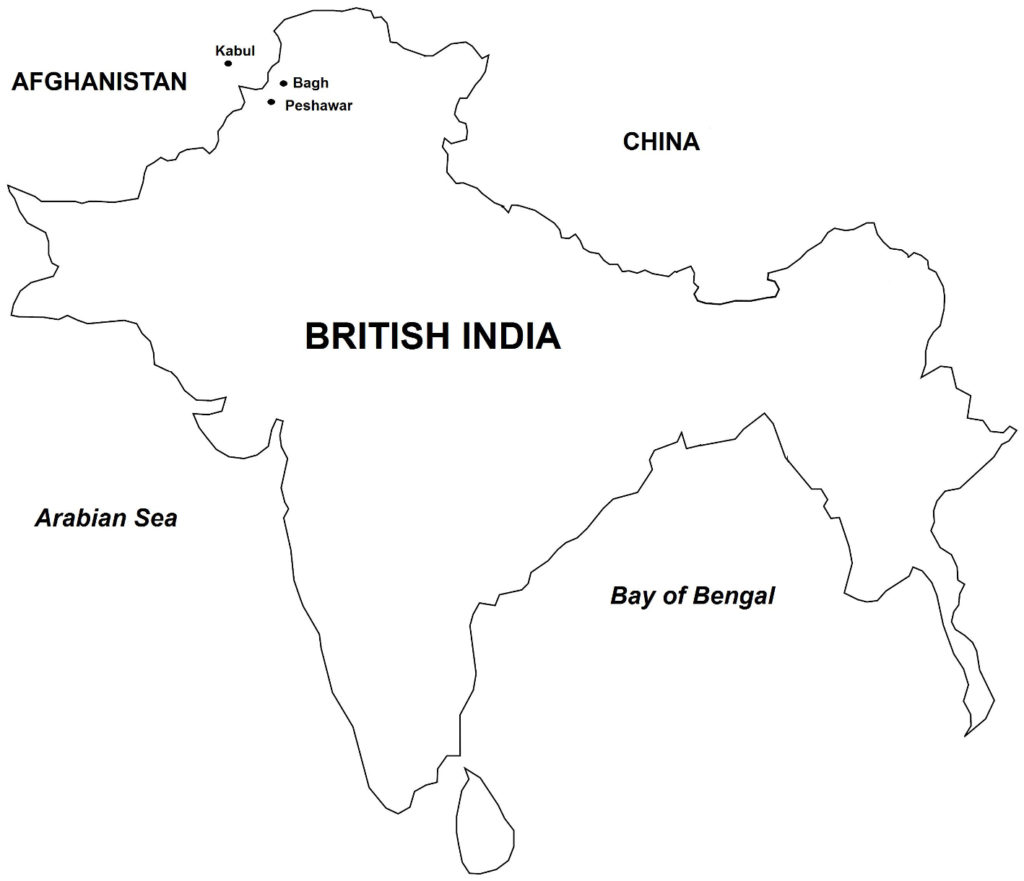

During the early years of the twentieth century, Tsarist Russia and the British Empire in India were the regional powers in Central Asia. The devastating effects of World War I on these two regional powers had a profound effect on the Anglo-Afghan War of 1919. In Russia, the Tsarist government had collapsed and a bitter civil war was raging. Consequently, Russia’s control of its Central Asian domains was weakened. The British Empire, which included the Indian subcontinent (Map 7), was drained financially and militarily, despite emerging victorious in World War I.

With the two regional powers weakened by war, the semi-independent Emirate of Afghanistan moved to assert its right of sovereignty. More important, Emir Habibullah, the Afghan ruler, wanted to annul the Treaty of Gandamak, where Afghanistan had ceded its foreign policy decisions to the British Empire. Adding strength to Emir Habibullah’s diplomatic position was that he had allowed Afghanistan to stay neutral during World War I, despite the strong anti-British sentiments among his people. Emir Habibullah had also spurned Germany and the Ottoman Empire, enemies of the British, who had encouraged him to defy British domination in the region and even launch an attack on British India, at a time when Britain was most vulnerable.

For these reasons, Emir Habibullah asked the British to allow him to present his case for Afghanistan’s independence at the Paris Peace Conference, where the victorious Allied countries had gathered to discuss the end of World War I. Habibullah was assassinated, however, before his case was decided. His son, Amanullah, succeeded to the Afghan throne, despite a rival claim by a family relative.

Upon his ascent to the throne on February 28, 1919, Emir Amanullah I declared Afghanistan’s independence, doing away with his father’s policy of trying to gain the country’s sovereignty through diplomatic means. The declaration of independence was immensely popular among Afghans, as nationalist sentiments ran high. Emir Amanullah therefore was able to consolidate his hold on power, even as some sectors opposed his leadership. Emir Amanullah provoked the British by inciting an uprising of the tribal people in Peshawar, British India. Using the uprising as a diversion, he sent his forces across the Afghan-British Indian border to capture the town of Bagh.

The British Army quickly quelled the Peshawar uprising and threw back the Afghan forces across the border. The Afghans clearly were unprepared for war – although having sufficient numbers of soldiers as well as being assisted by tribal militias, they possessed obsolete weapons, which even then were in short supply.

By contrast, the British were a modern fighting machine because of the technological advances they had made in World War I. The British suffered from a shortage of soldiers, since much of their forces had yet to return to India from their deployment to other British territories during World War I. The British air attacks on Kabul devastated Afghan morale, forcing Emir Amanullah to sue for peace.

Afghanistan and the British Empire entered into peace negotiations to end the war. In the peace treaty that emerged from these negotiations, the British granted conciliatory terms to the Afghans, including returning Afghanistan’s right of foreign policy. The British, therefore, essentially recognized Afghanistan as a sovereign state. By this time, Afghanistan already had been nominally independent, as it had established diplomatic relations with the newly formed Soviet Union and its independence was gaining recognition by the international community.

Afghanistan and the British Empire retained the Durand Line as their common border. After the war, Afghanistan continued to serve as a buffer zone between the Russians and the British, because of the end of the previous non-aggression treaties between Tsarist Russia and the British Empire following the emergence of the Soviet Union after the Russian Civil War.