By the early 1970s, the autonomy-seeking Iraqi Kurds were holding talks with the Iraqi government after a decade-long war (the First Iraqi-Kurdish War, separate article); negotiations collapsed and fighting broke out in April 1974, with the Iraqi Kurds being supported militarily by Iran. In turn, Iraq incited Iran’s ethnic minorities to revolt, particularly the Arabs in Khuzestan, Iranian Kurds, and Baluchs. Direct fighting between Iranian and Iraqi forces also broke out in 1974-1975, with the Iranians prevailing. Hostilities ended when the two countries signed the Algiers Accord on March 6, 1975, where Iraq yielded to Iran’s demand that the midpoint of the Shatt al-Arab was the common border; in exchange, Iran ended its support to the Iraqi Kurds.

Iraq was displeased with the Shatt concessions and to combat Iran’s growing regional military power, embarked on its own large-scale weapons buildup (using its oil revenues) during the second half of the 1970s. Relations between the two countries remained stable, however, and even enjoyed a period of rapprochement. As a result of Iran’s assistance in helping to foil a plot to overthrow the Iraqi government, Saddam expelled Ayatollah Khomeini, who was living as an exile in Iraq and from where the Iranian cleric was inciting Iranians to overthrow the Iranian government.

(Taken from Iran-Iraq War – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 4)

Background (continued) However, Iranian-Iraqi relations turned for the worse towards the end of 1979 when Ayatollah Khomeini was proclaimed as Iran’s absolute ruler. Each of the two rival countries resumed secessionist support for the various ethnic groups in the other country. Iran’s transition to a full Islamic State was opposed by the various Iranian ethnic minorities, leading to revolts by Kurds, Arabs, and Baluchs. The Iranian government easily crushed these uprisings, except in Kurdistan, where Iraqi military support allowed the Kurds to fend off Iranian government forces until late 1981 before also being put down.

Ayatollah Khomeini, in line with his aim of spreading Islamic revolutions across the Middle East, called on Iraq’s Shiite majority to overthrow Saddam and his “un-Islamic” government, and establish an Islamic State. In April 1980, a spate of violence attributed to the Islamic Dawa Party, an Iran-supported militant group, broke out in Iraq, where many Baath Party officers were killed and other high-ranking government officials barely escaped assassination attempts. In response, the Iraqi government unleashed repressive measures against radical Shiites, including deporting thousands who were thought to be ethnic Persians, as well as executing Grand Ayatollah Mohammad Baqir al-Sadr, which drew widespread condemnation from several Muslim countries as the religious cleric was highly regarded in the wider Islamic community.

Throughout the summer of 1980, many border clashes broke out between forces of the two countries, increasing in intensity and frequency by September of that year. As to the official start of the war, the two sides have different interpretations. The Iraqis cite September 4, 1980, when the Iranian Army carried out an artillery bombardment of Iraqi border towns, prompting Saddam two weeks later to unilaterally repeal the 1975 Algiers Accord and declare that the whole Shatt al-Arab lay within the territorial limits of Iraq.

September 22, 1980, however, is generally accepted as the start of the war, when Iraqi forces launched a full-scale air and ground offensive into Iran. Saddam believed that his forces were capable of achieving a quick victory, his confidence borne by the following factors, all resulting from the Iranian Revolution. First, as previously mentioned, Iran faced regional insurgencies from its ethnic minorities that opposed Iran’s adoption of Islamic fundamentalism. Second, Iran further was wracked by violence and unrest when secularist elements of the revolution (liberal democrats, communists, merchants and landowners, etc.) opposed the Islamist hardliners’ rise to power. The Islamic state subsequently marginalized these groups and suppressed all forms of dissent. Third, the revolution seriously weakened the powerful Iranian Armed Forces, as military elements, particularly high-ranking officers, who remained loyal to the Shah, was purged and repressive measures were undertaken to curb the military. Fourth, Iran’s newly established Islamic government, because it rejected both western democracy and communist ideology, became isolated internationally, even among Arab and Muslim countries.

Because of the United States’ support for Iran’s previous regime and in response to the U.S. government’s allowing the ailing Shah to seek medical treatment in the United States, hundreds of radical Iranian students broke into the U.S. Embassy in Tehran on November 4, 1979 and took hostage over sixty American diplomatic personnel and citizens. (This event, known as the Iran hostage crisis, ended on January 20, 1981 when the 52 remaining hostages were released.) In response, the United States ended diplomatic, economic, and later, military relations with Iran, and imposed economic sanctions and military restrictions. These U.S. sanctions were detrimental to Iran, in particular with regards to the coming war with Iraq, as the weapons and military hardware of the Iranian Armed Forces were sourced from the United States.

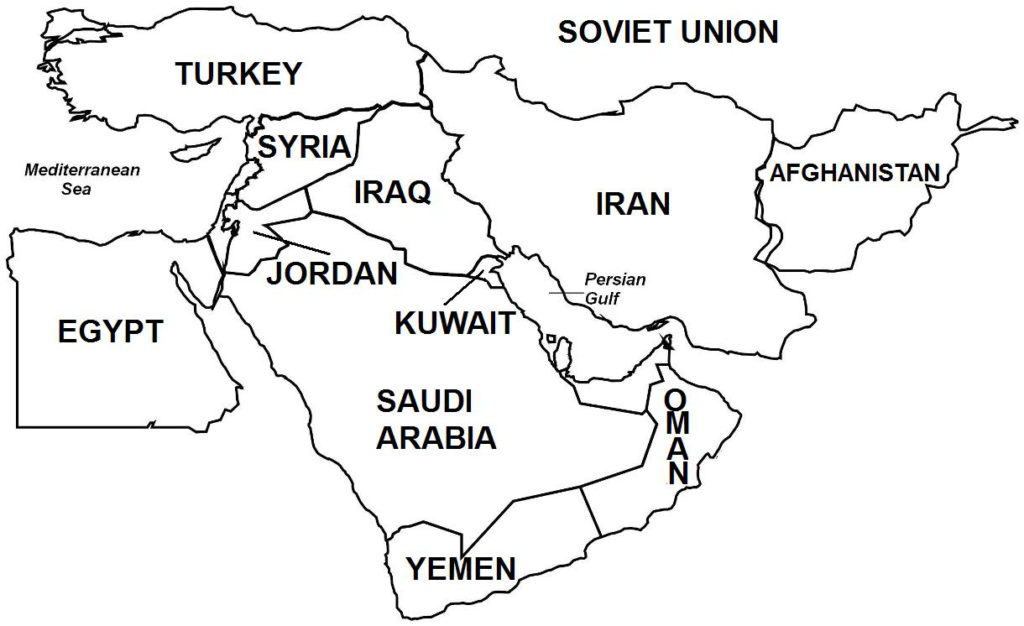

Saddam wanted to make Iraq the dominant power in the Middle East, a position traditionally held by Egypt but which Egyptian President Anwar Sadat had yielded politically after signing a peace agreement with Israel in March 1979. Iraq’s military buildup had, by the start of the war, boasted some 200,000 soldiers, 2,700 tanks, 1,000 artillery pieces, and 330 planes. By contrast, Iranian forces consisted of 150,000 soldiers, 1,700 tanks, 1,000 artillery pieces, and 440 planes.

Foreign Support The war saw the involvement of the two major superpowers, as both the United States and the Soviet Union, in the Cold War context, sought to gain favorable political, military, and economic outcomes from the conflict. The Soviet Union, long a supplier of military weapons to Iraq, backed Saddam, and also sought (unsuccessfully) to establish close ties with Iran. The United States initially was averse to both sides of the war, viewing Iraq as a Soviet satellite and an enemy of Israel, and Iran as an anti-American fanatical Islamic state. With the breakdown of relations with Iran resulting from the Tehran hostage crisis, the United States threw its support (somewhat ambivalently) behind Iraq.

Like the United States, Persian Gulf monarchies were disinclined toward either side in the war, opposing Iraq’s power ambitions and loathing Iran even more, because of Ayatollah Khomeini’s view that monarchical governments were un-Islamic, and encouraged their overthrow. But with Iran taking the military initiative by 1982, the Gulf monarchies, particularly Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, and the United Arab Emirates, became alarmed at a potential Iranian victory and released large sums of money, by way of loans, to Iraq. Israel also was averse to either side, as both countries held anti-Zionist policies, but ultimately supported Iran, viewing the Iraqi government’s more pronounced military involvement in the Arab-Israeli wars as the bigger threat.

Very few other countries were inclined to support Iran, which was considered an outcast in the international community and, throughout the coming war, would experience difficulty procuring weapons and spare parts for its American-made military equipment. Most Arab League states backed predominantly Arab Iraq against “Persian” (i.e. non-Arab) Iran. However, two Arab countries, Syria and Libya, backed and militarily supported Iran. Syria and Iraq had a long history of mutual distrust, while Libya, an enemy of Iran’s deposed Shah, had welcomed the Iranian Revolution and established close ties with Iran’s Islamic government. North Korea also sold weapons to Iran. Many other countries (e.g. China, the Soviet Union, Yugoslavia, Portugal, etc.), directly or through third-party arms dealers, sold weapons to both sides of the war.

Between 1985 and 1987, in an elaborate clandestine transaction, the United States provided weapons to Iran in exchange for the release of American hostages in Lebanon. This event, known as the Iran-Contra Affair, generated a breach in U.S. laws and led to a number of United States Congressional investigations involving high-level U.S. administration officials.

War An escalation of hostilities, including artillery exchanges and air attacks, took place in the period preceding the outbreak of war. On September 22, 1980, Iraq opened a full-scale offensive into Iran with its air force launching strikes on ten key Iranian airbases, a move aimed at duplicating Israel’s devastating and decisive air attacks at the start of the Six-Day War in 1967. However, the Iraqi air attacks failed to destroy the Iranian air force on the ground as intended, as Iranian planes were protected by reinforced hangars. In response, Iranian planes took to the air and carried out retaliatory attacks on Iraq’s vital military and public infrastructures.

Throughout the war, the two sides launched many air attacks on the other’s economic infrastructures, in particular oil refineries and depots, as well as oil transport facilities and systems, in an attempt to destroy the other side’s economic capacity. Both Iran and Iraq were totally dependent on their oil industries, which constituted their main source of revenues. The oil infrastructures were nearly totally destroyed by the end of the war, leading to the near collapse of both countries’ economies. Iraq was much more vulnerable, because of its limited outlet to the sea via the Persian Gulf, which served as its only maritime oil export route.

Iran, which possessed a powerful navy, imposed a naval blockade around the Persian Gulf, effectively land-locking Iraq, while Syria, Iran’s ally, closed down the Kirkuk-Banias oil pipeline, through which Iraq exported its petroleum via Syria. Iraq was left with the Kirkuk-Ceyhan outlet through Turkey, which also became vulnerable to attack later in the war when Iraqi Kurds of northern Iraq rose up in rebellion and became allied with Iran in the war.

Together with its air attacks on the first day of the war, Iraqi ground forces launched simultaneous offensives along three fronts: north, central, and south. The northern front advanced east of Sulaymaniyah, aimed at protecting northern Iraq’s vital installations, including the Kirkuk oil fields and Darbandikhan Dam. The central front also was strategically defensive and consisted of two operations, one in the north that advanced and successfully took Qasr-e Shirin toward the approaches of the Zagros Mountains, intended to guard the Baghdad-Tehran Highway; and one in the south that occupied Mehran, an important junction in Iran’s north-south road near the border with Iraq.

The southern front was the focus of the invasion, where five Iraqi divisions attacked the petroleum resource-rich Iranian province of Khuzestan, which generated 90% of Iran’s oil production. Iraqi forces used bridging equipment to cross the Shatt al-Arab and once on the Iranian side of the river, met little opposition and thus made rapid progress toward Khoramshahr and Susangerd. Iran was caught off-guard by the invasion and had stationed only an undermanned force to defend Khuzestan.