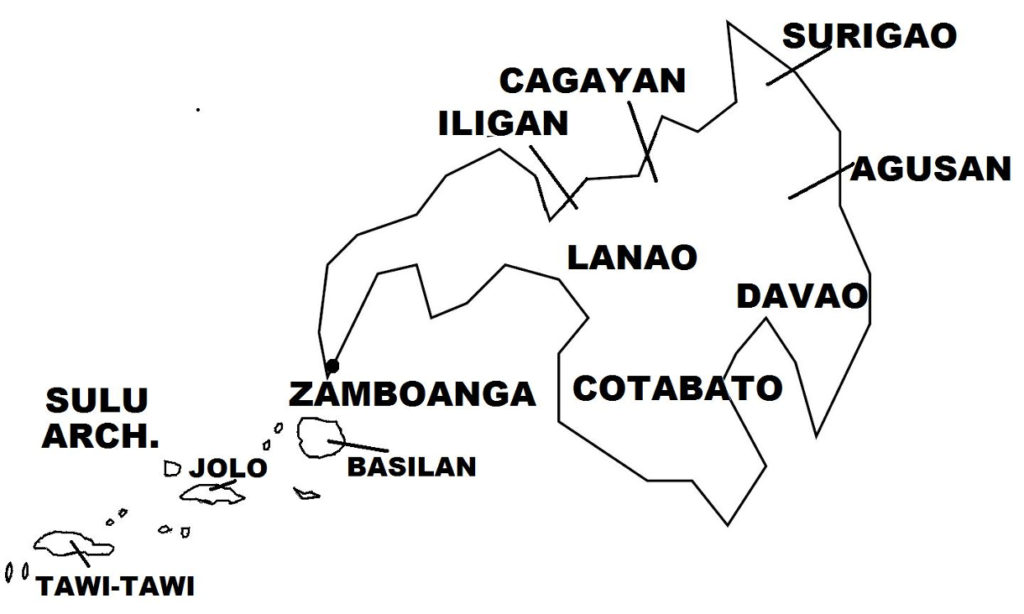

In Jolo, thousands of Moros, including women and children, and led by a fugitive named Pala (who was wanted by British authorities in Borneo) set up fortifications at Bud (Mount) Dajo, an extinct volcano five miles south of Jolo. In March 1906, U.S. forces stormed these fortresses in the encounter known as the Battle of Bud Dajo, resulting in perhaps all 900–1,000 Moros killed; U.S. Army casualties were 21 killed and 75 wounded.

American colonial authorities in the Philippines tried to suppress information in the United States regarding the Battle of Bud Dajo, but details of the encounter that surfaced in U.S. news services generated outrage from the American public and a firestorm of controversy that reached the top levels of the U.S. government. Particularly alarming was the report that the “wanton slaughter” of Moro women and children had taken place. Legislators of the opposition Democratic Party condemned General Wood’s conduct of the battle, and put pressure on President Theodore Roosevelt. The U.S. Congress asked the War Department to turn in the battlefield reports from the Bud Dajo operation. Nevertheless, the Republican Party stood behind General Wood, while military authorities explained that the presence of women and children in the Moro cotas during the battle naturally led to high civilian casualties, and that the women were armed and fought alongside the men, and that the Moros used their children as “human shields”.

(Taken from Moro Rebellion – Wars of the 20th Century – Twenty Wars in Asia)

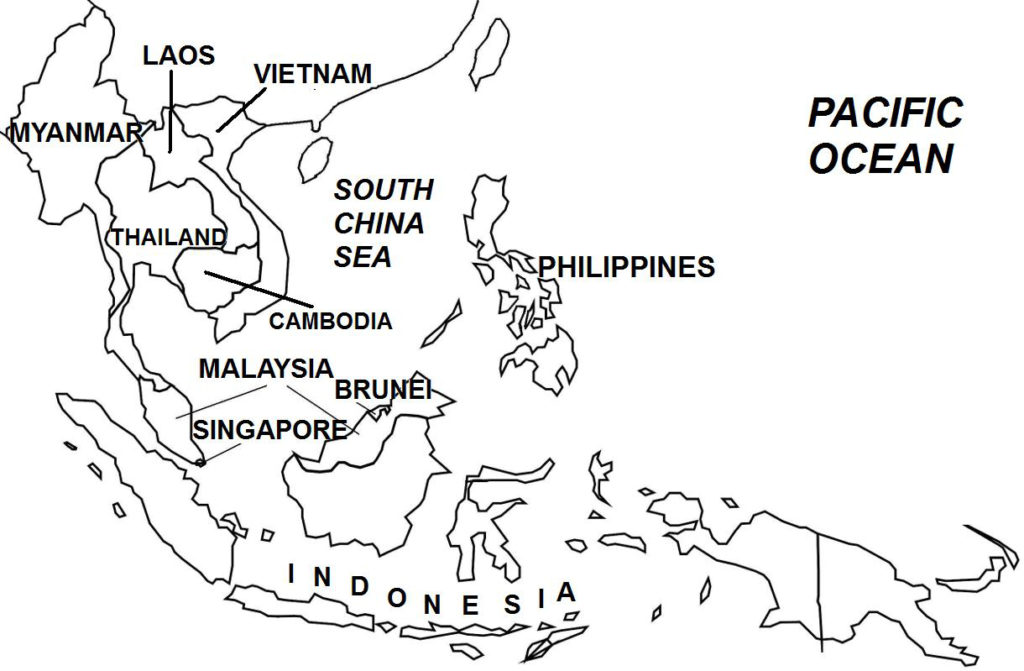

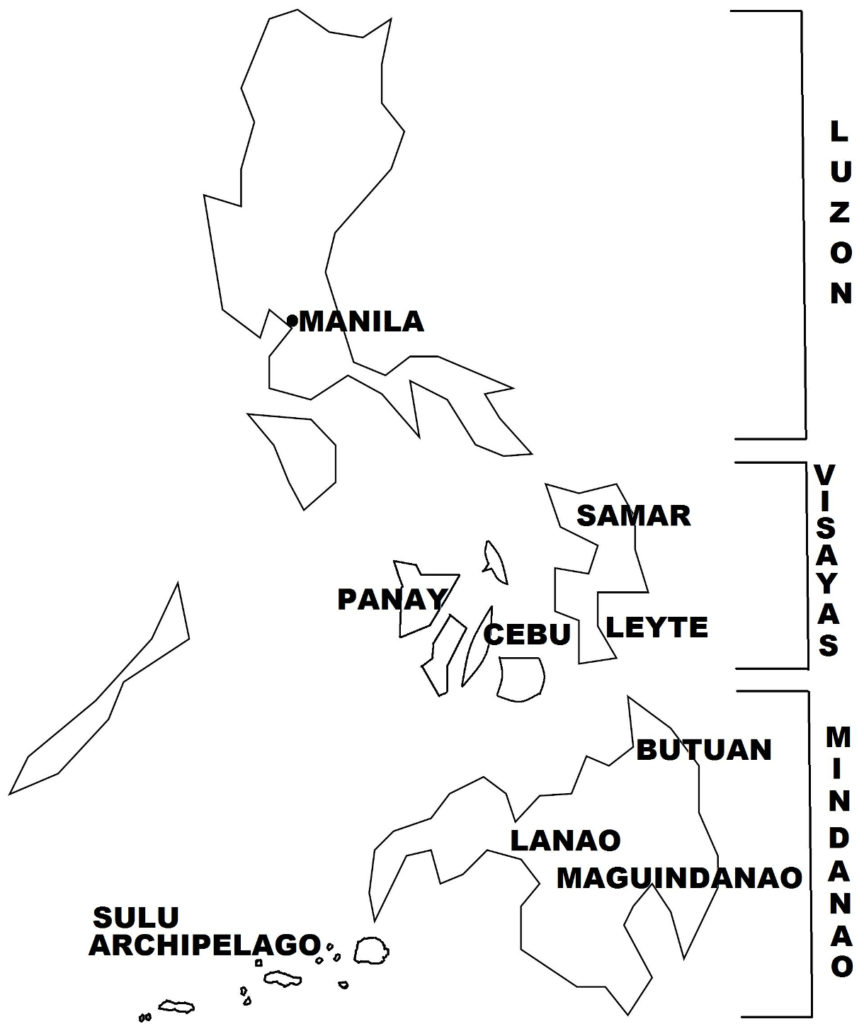

The Moros During much of its colonization of the islands, Spain was unable to bring under its control the southern part of the Philippine archipelago, comprising the main island of Mindanao and, to its west, the Sulu Archipelago. A great majority of the native population in these regions was Muslim, whom the Spanish called “Moros”, a term they originally ascribed to North African Muslims who invaded and occupied the Iberian Peninsula from the 8th to 15th centuries. Pre-occupation with the Galleon Trade, inadequate military resources, irresoluteness, and the difficulty of converting Muslims prevented Spain from penetrating the vast, hostile interior of Mindanao. The Spanish did launch a number of operations in Moroland, and although they achieved victory in battle as a result of superior firepower, these attacks ultimately were not successful in totally subduing the Moros.

The Moros practiced slavery, and launched slave-raiding attacks using swift war boats on the Christian towns and villages, particularly in the Visayas, and also in Luzon, and carried off the inhabitants of these areas into slavery. The Moros plundered settlements, and burned houses, churches, and buildings. In the 18th century, Moro raids were taking a heavy toll on Spanish resources as a result of the destruction and also the great cost to rebuild the communities, livelihoods, and infrastructures of the affected areas.

In reprisal for these attacks, the Spanish launched punitive expeditions in Moro areas, which in turn, incited reciprocal attacks from the Moros, leading to a constant cycle of raids and counter-raids. By the 17th to early 18th centuries, a perennial state of war existed between Spanish-controlled Luzon and the Visayas, and Moro-dominated Mindanao and Sulu. This period coincided with the reign of Sultan Kudarat, who greatly extended the territories of the Sultanate of Maguindanao to include much of present-day Mindanao through alliances with other sultanates and other Moro tribes. In general, however, the Moros, who comprised many diverse ethnic groups, did not form a united front against the Spaniards; in fact, the various Moro city-states were sworn enemies, and fought the Spanish, as they did each other.

In the mid-19th century, Spain introduced steam-powered ships to the Sulu Archipelago, which finally stopped the Moro piratical attacks. The Spanish vessels greatly outmatched the Moro war boats in speed and power. The Spanish also attacked Moro pirate lairs, and imposed a naval blockade of Jolo, preventing Moros from bringing in firearms from abroad. By the late 1870s, Moro piracy was quelled. At this time also, the Spanish were able to establish several coastal garrisons in Mindanao, from where they launched military expeditions on Moro fortified settlements (called “cotas”) in the island’s interior, particularly against the powerful Maguindanao and Lanao sultanates.

Earlier in 1848 and 1851, Spanish forces attacked Jolo, the seat of the Sulu Sultanate. The Sulu Sultan was forced to move his capital to another section of the island, which allowed the Spanish Army to establish a garrison in Jolo. In 1876, the Spanish Army, assembling a large force of 9,000 soldiers and a fleet of gunboats, attacked Jolo again, this time decisively defeating the forces of the Sulu Sultan. The Spanish then gained full control of Jolo Island.

In July 1878, Spain and the Sulu Sultanate signed a peace treaty called the “Bases of Peace and Capitulation”, which differed in translations between the Spanish and Sultanate’s versions. In the former’s version, Spain was granted full sovereignty over the Sultanate and its territory (i.e. the Sultanate, as a sovereign political entity, ceased to exist), while in the latter’s version, the Sultanate was a protectorate of Spain (i.e. it retained its sovereignty, but was under Spanish protection). In March 1885, Britain, Germany, and Spain, desiring to define their territorial jurisdictions and spheres of interests, signed the Madrid Protocol, which stipulated that the Philippine Islands, including Mindanao and the Sulu Archipelago, was officially recognized as belonging to Spain.

By the time of the Philippine Revolution (in August 1896) and later the United States involvement in the Philippines during the Spanish-American War (May 1898), Spain was in the process of consolidating its authority in the Sulu Archipelago, and had established in Mindanao a number of garrisons (in Jolo, Zamboanga, Iligan, Cagayan, Surigao, Cotabato, Davao, etc.) from where they launched expeditions against the Moros in the interior. In these coastal areas, Christian settlements also were established, as Spanish authorities encouraged the native Christians from Luzon and the Visayas to resettle in Mindanao. While most of the Moro sultanates and smaller city-states resisted the Spanish intrusions, a number of Moro chieftains were co-opted to work with the Spanish, and even to fight defiant Moro sultans and datus.

In December 1898, Spain and the United States ended their state of war with the signing of the Treaty of Paris, where Spain ceded to the United States the Philippines (as well as Cuba, Puerto Rico, and Guam). Filipino revolutionaries in Luzon and the Visayas, who had been fighting an independence war against Spain since 1896, then declared war on the United States, resulting in the three-year Philippine-American War (June 1899 – July 1902). The U.S. colonial authorities, preoccupied with the war in the north against the Filipino revolutionaries, applied a policy of non-interference with the Moros in the south in order to not be embroiled simultaneously in two wars. However, U.S. Army units occupied the former Spanish coastal garrisons in Mindanao and Sulu.

In August 1899, the United States and the Sulu Sultanate signed the Bates Agreement (named after U.S. General John Bates, who negotiated for the U.S. government), where the United States established a protectorate over the Sulu Sultanate in exchange for allowing the Moros to maintain their local autonomy, laws, religion and culture. Slavery, which was widely practiced by the Moros, was tacitly tolerated, but would become a contributory factor to the coming war between the United States and the Moro people.

By mid-1902, the Philippine-American War was winding down, and the U.S. Army quelled the last major Filipino revolutionary resistance in Luzon and the Visayas. By this time, conflict with the Moros in southern Philippines also had broken out. Imminent victory in the north also allowed the U.S. military to move more troops to the south to confront the Moros, whom the U.S. government now was determined to bring under its full authority. In July 1902, the U.S. War Department announced that the war with the Filipino revolutionaries was over, but this did not extend to Moroland as stipulated in Proclamation 483 issued by U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt, who declared that “…the insurrection against the authority and sovereignty of the United States is now at an end, and peace has been established in all parts of the archipelago except in the country inhabited by the Moro tribes, to which this proclamation does not apply”.