The Greek Army of Epirus, having been reinforced to 41,000 soldiers, began its offensive on Iaonnina. On March 6, 1913, the Greeks broke through the Ottoman lines at Bizani after three days of fighting. Iaonnina fell soon thereafter. The Greek Army then advanced north, capturing sections of southern Albania.

On April 20, 1913, peace negotiations in London resumed. This time, the European powers (Britain, France, Germany, Austria-Hungary, Italy, and Russia) applied strong pressure, forcing the warring sides to accept a prepared agreement (the Treaty of London), which was signed on May 30, 1913 and officially ended the war. The treaty’s most important provision forced the Ottoman Empire to cede to the Balkan League all European territory west of the Enos-Midia Line.

The Ottoman government complied and withdrew its forces from the Balkans, thus ending nearly five centuries of Ottoman rule in practically all of Europe. After further deliberations and under strong insistence of Austria-Hungary and Italy, on July 29, 1913, the European powers agreed to recognize the independence of Albania, where local Albanian nationalists had previously (on November 28, 1912) declared the province’s secession from the Ottoman Empire. As a result, Serbia, Greece, and Montenegro withdrew their forces from occupied areas in Albania, again after being strong-armed diplomatically by the European powers.

The partitioning of other Balkan territories was left to the discretion of the Balkan League. Nevertheless, the unexpected birth of the Albanian state disrupted the Serbian-Bulgarian pre-war secret partition agreement of the Balkan region. In particular, Bulgaria was disappointed at its less than expected territorial gains in the war, more so in relation to Greece whose forces had performed exceedingly (and surprisingly) well, and had gained a larger share of the conquered territories in southern Macedonia that otherwise would have been won by Bulgaria. For this reason, Bulgaria put pressure on Serbia and Greece to turn over some of the conquered territories, which the latter two refused.

The stage thus was set for the resumption of hostilities, the Second Balkan War.

(Taken from First Balkan War – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 3)

Background of the First Balkan War At the start of the twentieth century, the Ottoman Empire was a spent force, a shadow of its former power of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries that had struck fear in Europe. The empire did continue to hold vast territories, but only tolerated by competing interests among the European powers who wanted to maintain a balance of power in Europe. In particular, Britain and France supported and sometimes intervened on the side of the Ottomans in order to restrain expansionist ambitions of the emerging giant, the Russian Empire.

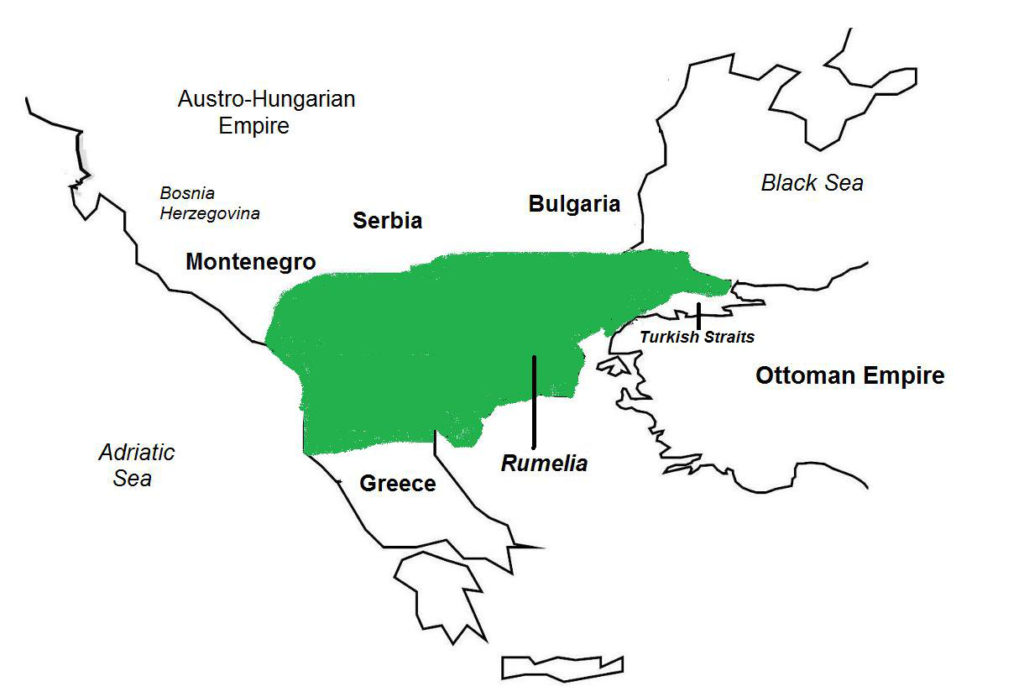

In Europe, the Ottomans had lost large areas of the Balkans, and all of its possessions in central and central eastern Europe. By 1910, Serbia, Bulgaria, Montenegro, and Greece had gained their independence. As a result, the Ottoman Empire’s last remaining possession in the European mainland was Rumelia (Map 4), a long strip of the Balkans extending from Eastern Thrace, to Macedonia, and into Albania in the Adriatic Coast. And even Rumelia itself was coveted by the new Balkan states, as it contained large ethnic populations of Serbians, Belgians, and Greeks, each wanting to merge with their mother countries.

The Russian Empire, seeking to bring the Balkans into its sphere of influence, formed a military alliance with fellow Slavic Serbia, Bulgaria, and Montenegro. In March 1912, a Russian initiative led to a Serbian-Bulgarian alliance called the Balkan League. In May 1912, Greece joined the alliance when the Bulgarian and Greek governments signed a similar agreement. Later that year, Montenegro joined as well, signing separate treaties with Bulgaria and Serbia.

The Balkan League was envisioned as an all-Slavic alliance, but Bulgaria saw the need to bring in Greece, in particular the modern Greek Navy, which could exert control in the Aegean Sea and neutralize Ottoman power in the Mediterranean Sea, once fighting began. The Balkan League believed that it could achieve an easy victory over the Ottoman Empire, for the following reasons. First, the Ottomans currently were locked in a war with the Italian Empire in Tripolitania (part of present-day Libya), and were losing; and second, because of this war, the Ottoman political leadership was internally divided and had suffered a number of coups.

Most of the major European powers, and especially Austria-Hungary, objected to the Balkan League and regarded it as an initiative of the Russian Empire to allow the Russian Navy to have access to the Mediterranean Sea through the Adriatic Coast. Landlocked Serbia also had ambitions on Bosnia and Herzegovina in order to gain a maritime outlet through the Adriatic Coast, but was frustrated when Austria-Hungary, which had occupied Ottoman-owned Bosnia and Herzegovina since 1878, formally annexed the region in 1908.

The Ottomans soon discovered the invasion plan and prepared for war as well. By August 1912, increasing tensions in Rumelia indicated an imminent outbreak of hostilities.