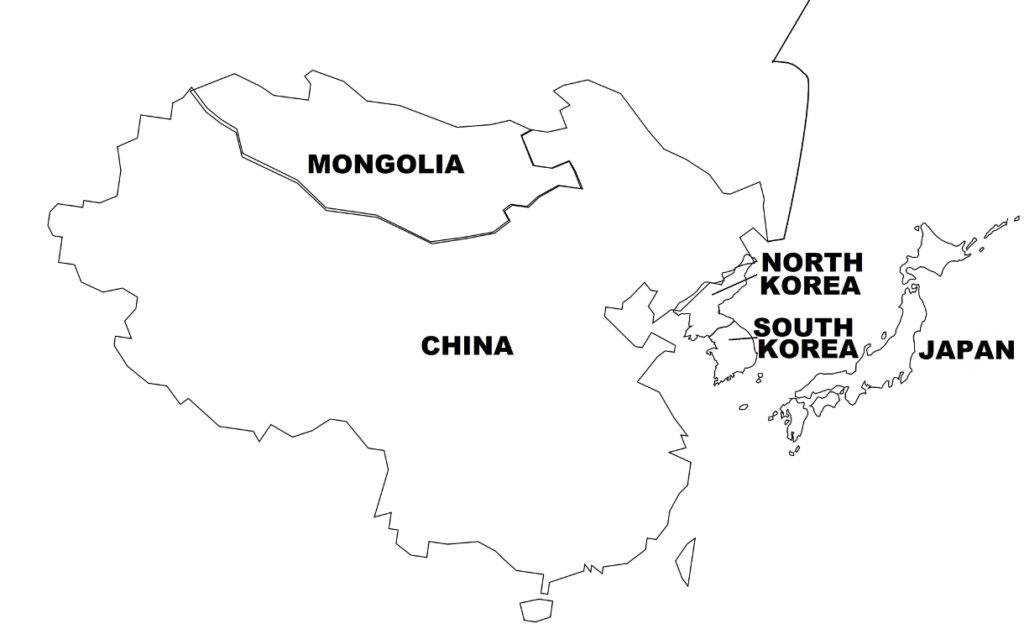

On July 10, 1951, representatives from the warring sides, China and North Korea on the one hand, and the United States, South Korea, and the United Nations on the other, opened armistice talks at Kaesong to end the Korean War. Kaesong (now part of North Korea) was located near the northern edge of the battle lines. Negotiations proved lengthy and contentious and proceeded slowly, with long intervals between meetings. Talks were later moved to Panmunjom, a nearby village, where an armistice would be signed in July 1953.

(Excerpts taken from Wars of the 20th Century – Twenty Wars in Asia)

Continuing hostilities before and during the armistice talks U.S. and South Korean forces settled down to a defensive posture, fortifying existing positions. Meanwhile at the United Nations, American and Soviet delegates met to try and end the war. Then on June 23, 1951, the Soviet representative to the UN proposed an armistice between China and North Korea on the one hand, and the United States, South Korea, and the UN, on the other hand, a proposal that was received favorably by the U.S. and Chinese governments. On July 10, 1951, delegates from the warring parties opened armistice talks at Kaesong. Within a few months, negotiations were moved six miles east to Panmunjom, which became the permanent site of negotiations. Subsequently, for the Korean War, the active phase of full-scale warfare came to an end.

Kim Il-sung and Syngman Rhee, leaders of North Korea and South Korea, respectively, strongly opposed the peace negotiations and wanted to continue the war, as both were determined to reunify the Korean Peninsula by force under their rule. But without the support of the major powers, the two Korean governments were forced to back down. The negotiations proved long and arduous, and ultimately lasted two years (July 1951-July 1953) punctuated by a number of stoppages in the talks. During this period, the fighting produced no major territorial changes, leading to a stalemate in the battlefield.

One major cause of the delay in the settlement was that the war had produced an uneven line across the 38th parallel, with the central and eastern sections being north of the parallel and the western section being south of the parallel, and with a net territorial loss to North Korea. Chinese and North Korean delegates argued that the 38th parallel must be the armistice line, which American and South Korean representatives opposed, stating that the current frontlines must be the armistice line, as these are much more defensible compared to the topography along the 38th parallel. By late 1951, with no agreement reached and fighting continuing, the communist side dropped its demand of opposing forces returning to the 38th parallel, and the two warring sides came to an agreement that the frontlines during the time of the signing of a truce would serve as the armistice line.

A second major point of contention was the issue of the prisoners of war (POWs). UN forces held some 150,000 Chinese and North Korean POWs, of which a sizable number refused to be repatriated back to the their homelands, which provoked China and North Korean to accuse UN forces of using underhanded methods to prevent repatriation. In particular, the Chinese government claimed that anti-communist Chinese POWs were allowed to torture communist Chinese POWs to force the latter to refuse being repatriated. In one notable event in mid-June 1953 (one month before the armistice agreement was signed), the South Korean government released some 27,000 anti-communist North Korean POWs, stating that the prisoners had escaped from prison.

On the UN side, American and South Korean POWs were much more subject to physical abuse than other UN prisoners, especially by their North Korean captors. American POWs suffered from tortures, starvation, and forced labor, if not being outright executed. UN prisoners in Chinese POW camps rarely were executed, but suffered mass starvation, particularly in the 1950-1951 winter, where nearly half of all U.S. POWs died from hunger. Responding to accusations by the Truman administration that American POWs were being ill-treated, the Chinese government stated that because its logistical system suffered severe inadequacies, food shortages were widespread at the frontlines, and in fact thousands of its own troops also perished from starvation (as well as from the sub-zero harsh winter conditions).

Furthermore, 80,000 South Korean soldiers remained missing, whom the UN command and South Korean government believed had been captured by North Korean forces, and were then coerced into joining the North Korean Army or were being used as forced laborers. North Korea rejected these accusations, saying that it had only 10,000 South Korean POWs, that its other POWs already had been released or were killed by the UN air attacks, and that it did not use forced recruitment into its armed forces. As a result, the fates of the missing South Korean POWS remained undetermined after the war.

The armistice talks ended the period of large-scale offensives. Then during the ensuing two-year period of stalemate, only small- to medium-scale limited-scope battles took place. Most of these battles were initiated by UN forces, and were aimed at gaining territory that would give the UN forces better strategic and defensive positions.

In September-October 1951, after negotiations temporarily broke down, American and South Korean forces launched a limited operation in the central sector, advancing seven miles north of the Kansas Line. In the western sector, UN forces also succeeded in establishing new positions north of the Wyoming Line.

U.S. planes continued its domination of the skies, attacking enemy road and rail networks, supply centers, and ammunition depots. In 1952, U.S. air strikes in North Korea increased. The vital hydroelectric facility at Suiho was attacked in July, and Pyongyang was subject to a large raid in August. The attack on the North Korean capital, which involved 1,400 air sorties, was the largest single-day air operation of the war.

In May 1952, General Mark Clark became the new commander of UN forces, replacing General Ridgway. In June 1952, after a series of fierce clashes, U.S. forces dislodged the enemy from the heights in Chorwon County, and established 11 patrol bases in a number of hills, including the highest and most strategically important hill called “Old Baldy”. Many intense battles took place during the second half of 1952, as Chinese and North Korean forces attacked UN frontline outposts in response to U.S. air raids in North Korea. By this time, UN forces had adopted a defensive posture, and fortified their positions with trenches, bunkers, minefields, barbwire, and other obstacles all across the UN main line of resistance from east to west of the peninsula.

In spring 1953, Chinese forces again put pressure on UN lines. But by now with fortified positions on both sides, the mounting casualties, the absence of large-scale offensives, and the stalemated battlefield situation, the deadlock appeared to last indefinitely. In April 1953, peace talks resumed. Six months earlier, on November 29, 1952, President-elect Dwight Eisenhower, who had just won the U.S. presidential elections three weeks earlier and had promised to end the war, visited Korea to determine how the negotiations could be accelerated. He also threatened to use nuclear weapons in response to a build-up of Chinese forces in the western sector of the line. Furthermore, with the death of Soviet hard-line leader Joseph Stalin in March 1953, the new Soviet government was more conciliatory with the West, and put pressure on China to reach a peace settlement in Korea.

On April 20-26, 1953, under Operation Little Switch, both sides exchanged sick and wounded POWs. In May-June 1953, as peace talks continued, Chinese forces launched limited attacks on UN positions, which were repulsed with heavy Chinese losses by American air, armored, and artillery firepower.

On June 18, 1953, the armistice negotiations produced a mutually acceptable agreement. However, the agreement was rejected by South Korean President Rhee, and shelved. Taking advantage of the new stalemate, on July 6, 1953, the Chinese renewed their offensive, first attacking a UN outpost known as Pork Chop Hill, which forced the defending American troops of the U.S. 7th Division to retreat after four days of fighting, with heavy losses to both sides.

Then on July13, 1953, in the last major battle of the war, a massive Chinese force of 250,000 troops, supported with heavy artillery (over 1,300 artillery pieces), struck at UN positions on a 22-kilometer front, pushing the mainly defending South Korean forces 50 kilometers south and gaining 190 km2 of territory. However, the victory was pyrrhic, as the Chinese casualties numbered some 60,000 troops, compared to South Korean losses of 14,000 troops.

Meanwhile, armistice talks resumed, which culminated in an agreement on July 19, 1953. Eight days later, July 27, 1953, representatives of the UN Command, North Korean Army, and the Chinese People’s Volunteer Army signed the Korean Armistice Agreement, which ended the war. A ceasefire came into effect 12 hours after the agreement was signed. The Korean War was over.

War casualties included: UN forces – 450,000 soldiers killed, including over 400,000 South Korean and 33,000 American soldiers; North Korean and Chinese forces – 1 to 2 million soldiers killed (which included Chairman Mao Zedong’s son, Mao Anying). Civilian casualties were 2 million for South Korea and 3 million for North Korea. Also killed were over 600,000 North Korean refugees who had moved to South Korea. Both the North Korean and South Korean governments and their forces conducted large-scale massacres on civilians whom they suspected to be supporting their ideological rivals. In South Korea, during the early stages of the war, government forces and right-wing militias executed some 100,000 suspected communists in several massacres. North Korean forces, during their occupation of South Korea, also massacred some 500,000 civilians, mainly “counter-revolutionaries” (politicians, businessmen, clerics, academics, etc.) as well as civilians who refused to join the North Korean Army.