French Prime Minister Charles de Gaulle weakened the French Algerian Army’s radicalism when on January 19, 1960, he dismissed General Jacques Massu, victor of the Battle of Algiers, who had threatened insubordination by declaring that he and other officers may choose to not follow de Gaulle’s orders. Three months later, in April 1960, de Gaulle reassigned General Challe, commander-in-chief of the French Algerian Army, away from Algeria, just as the latter was on the verge of inflicting a decisive defeat on the FLN “internal” forces.

(Taken from Algerian War of Independence – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 4)

General Massu’s dismissal sparked the “Week of Barricades” (French: La semaine des barricades) starting on January 24, 1960, where some 30,000 pieds-noirs took to the streets, seized government buildings, and set up barricades in an act of defiance against de Gaulle’s government. Viewing these acts as a threat to his regime, de Gaulle, donning his World War II brigadier general’s uniform in a televised broadcast on January 29, 1960, appealed to the French people and armed forces to remain loyal to France. The French 10th Parachute Division, which had won the Battle of Algiers for France, did not launch suppressive action against the barricades, but the refusal of the French Army to join the protesters doomed the uprising. The French 25th Parachute Division finally broke up the barricades; casualties for the protesters were 22 dead and 147 wounded, and for the Algerian gendarmes (police), 14 dead and 123 wounded.

A further sign of de Gaulle’s shift in policy toward Algeria took place in June 1960 when he took up a truce offer by a regional leader of the National Liberation Front (FLN; French: Front de Libération Nationale) and negotiate a “warrior’s peace” (French: la paix des braves); however, peace talks held in Melun (in France) failed. Then by November 1960, de Gaulle had decided on Algeria’s fate. On November 4, he declared that “there will be an Algerian republic one day, which will not be France”. He further stated a “new course”, i.e. an “emancipated Algeria…which, if the Algerians so desire…will have its own government, its institutions, and its laws”. De Gaulle then prepared a referendum for France and Algeria to determine whether Algeria should be given self-determination.

By the early 1960s, de Gaulle was shifting his foreign and economic priorities to Europe primarily by boosting France’s rapidly improving relations with Germany, which ultimately led to the signing, together with Italy, Belgium, Netherlands, and Luxembourg, of the Treaty of Rome in March 1957 that established the European Economic Council (EEC, precursor of the European Union). Furthermore, in the context of the Cold War rivalry between the United States and Soviet Union, de Gaulle wanted to make France, despite its alignment with the West through the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), a political and military “third force” separate from the two superpowers.

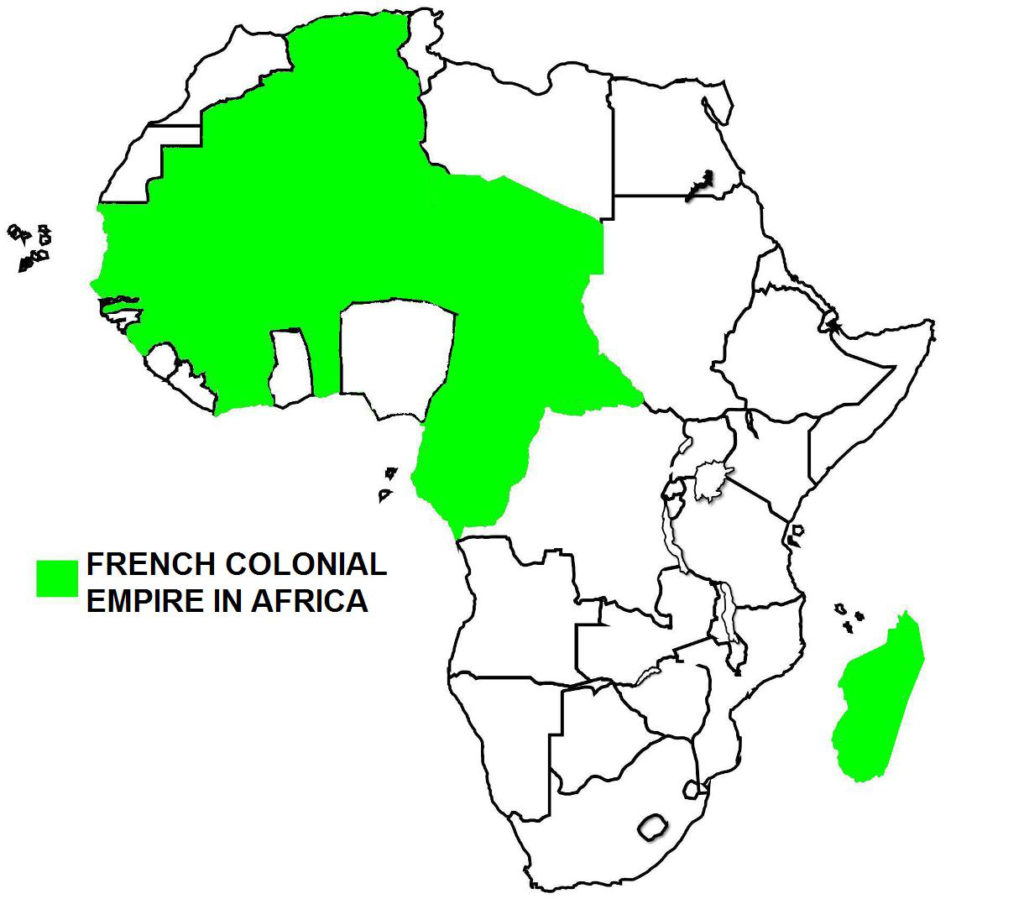

De Gaulle’s plan to disengage from Algeria was merely one episode in the decolonization process that France had undertaken in Africa in 1960: by the end of that year, the once vast French West Africa had given way to 13 independent countries. Similarly, the British Empire (which together with France held the greatest colonial territorial share of Africa) also had begun the process of decolonization in 1960 (apart from Ghana, which gained independence in 1957), having been triggered in February of that year when British Prime Minister Harold Macmillan issued his “Wind of Change” speech, declaring that in Africa, “the wind of change is blowing” and “whether we like it or not, this growth of national consciousness is a political fact”. Also in 1960, Belgium turned over political authority to a newly independent Democratic Republic of the Congo and would do the same to Rwanda and Burundi in 1962. Portugal and Spain tried to hold onto their African possessions, but in the ensuing years, became mired in long and bitter independence wars against indigenous nationalist movements.

Furthermore, on December 14, 1960, the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) passed Resolution 1514 (XV) titled “Declaration of the Granting of Independence to Colonial Countries and Peoples”, which established decolonization as a fundamental principle of the UN. Five days later, on December 19, the UN released UNGA Resolution 1573 that recognized the right of self-determination of the Algerian people.

On January 8, 1961, in a referendum held in France and Algeria, 75% of the voters agreed that Algeria must be allowed self-determination. The French government then began to hold secret peace negotiations with the FLN. In April 1961, four retired French Army officers (Generals Salan, Challe, André Zeller, and Edmond Jouhaud, and assisted by radical elements of the pied-noir community) led the French command in Algiers in a military uprising that deposed the civilian government of the city and set up a four-man “Directorate”. The rebellion, variously known as the 1961 Algiers Putsch (French: Putsch d’Alger) or Generals’ Putsch (French: Putsch des Généraux), was a coup to be carried out in two phases: taking over authority in Algeria with the defeat of the FLN and establishment of a civilian government; and overthrowing de Gaulle in Paris by rebelling paratroopers based near the French capital.

De Gaulle invoked the constitution’s provision that gave him emergency powers, declared a state of emergency in Algeria, and in a nationwide broadcast on April 23, appealed to the French Army and civilian population to remain loyal to his government. The French Air Force flew the empty air transports from Algeria to southern France to prevent them from being used by rebel forces to invade France, while the French commands in Oran and Constantine heeded de Gaulle’s appeal and did not join the rebellion. Devoid of external support, the Algiers uprising collapsed, with Generals Challe and Zeller being arrested and later imprisoned by military authorities, together with hundreds of other mutineering officers, while Generals Salan and Jouhaud went into hiding to continue the struggle with the pieds-noirs against Algerian independence.

On April 28, 1961, in the midst of the uprising, French military authorities test-fired France’s first atomic bomb in the Sahara Desert, moving forward the date of the detonation ostensibly to prevent the nuclear weapon from falling into the hands of the rebel troops. The attempted coup dealt a serious blow to French Algeria, as de Gaulle increased efforts to end the war with the Algerian nationalists.

In May 1961, the French government and the GPRA (the FLN’s government-in-exile) held peace talks at Évian, France, which proved contentious and difficult. But on March 18, 1962, the two sides signed an agreement called the Évian Accords, which included a ceasefire (that came into effect the following day) and a release of war prisoners; the agreement’s major stipulations were: French recognition of a sovereign Algeria; independent Algeria’s guaranteeing the protection of the pied-noir community; and Algeria allowing French military bases to continue in its territory, as well as establishing privileged Algerian-French economic and trade relations, particularly in the development of Algeria’s nascent oil industry.

In a referendum held in France on April 8, 1962, over 90% of the French people approved of the Évian Accords; the same referendum held in Algeria on July 1, 1962 resulted in nearly six million voting in favor of the agreement while only 16,000 opposed it (by this time, most of the one million pieds-noirs had or were in the process of leaving Algeria or simply recognized the futility of their lost cause, thus the extraordinarily low number of “no” votes).

However, pied-noir hardliners and pro-French Algeria military officers still were determined to derail the political process, forming one year earlier (in January 1961) the “Organization of the Secret Army” (OAS; French: Organisation de l’armée secrète) led by General Salan, in a (futile) attempt to stop the 1961 referendum to determine Algerian self-determination. Organized specifically as a terror militia, the OAS had begun to carry out violent militant acts in 1961, which dramatically escalated in the four months between the signing of the Évian Accords and the referendum on Algerian independence. The group hoped that its terror campaign would provoke the FLN to retaliate, which would jeopardize the ceasefire between the government and the FLN, and possibly lead to a resumption of the war. At their peak in March 1962, OAS operatives set off 120 bombs a day in Algiers, targeting French military and police, FLN, and Muslim civilians – thus, the war had an ironic twist, as France and the FLN now were on the same side of the conflict against the pieds-noirs.

The French Army and OAS even directly engaged each other – in the Battle of Bab el-Oued, where French security forces succeeded in seizing the OAS stronghold of Bab el-Oued, a neighborhood in Algiers, with combined casualties totaling 54 dead and 140 injured. The OAS also targeted prominent Algerian Muslims with assassinations but its main target was de Gaulle, who escaped many attempts on his life. The most dramatic of the assassination attacks on de Gaulle took place in a Paris suburb where a group of gunmen led by Jean-Marie Bastien-Thiry, a French military officer, opened fire on the presidential car with bullets from the assailants’ semi-automatic rifles barely missing the president. Bastien-Thiry, who was not an OAS member, was arrested, put on trial, and later executed by firing squad.

In the end, the OAS plan to provoke the FLN into launching retaliation did not succeed, as the Algerian revolutionaries adhered to the ceasefire. On June 17, 1962, the OAS the FLN agreed to a ceasefire. The eight-year war was over. Some 350,000 to as high as one million people died in the war; about two million Algerian Muslims were displaced from their homes, being forced by the French Army to relocate to guarded camps.

Aftermath of the Algerian War of Independence On July 3, 1962, two days after the second referendum for independence, de Gaulle recognized the sovereignty of Algeria. Then on July 5, 1962, exactly 132 years after the French invasion in 1830, Algeria declared independence and in September 1962, was given its official name, the “People’s Democratic Republic of Algeria” by the country’s National Assembly.

In the months leading up to and after Algeria’s independence, a mass exodus of the pied-noir community took place, with some 900,000 (90% of the European population) fleeing hastily to France. The European Algerians feared for their lives despite a stipulation in the Évian Accords that independent Algeria must respect the rights and properties of the pied-noir community in Algeria. Some 100,000 would remain, but in the 1960s through 1970s, most were forced to leave as well, as the war had scarred permanently relations between the indigenous Algerians and pieds-noirs, forcing the latter to abandon homes and properties under the threat of “the suitcase or the coffin” (French: “la valise ou le cercueil”). In France, the pieds-noirs experienced a difficult period of transition and adjustment, as many families had lived for many generations in Algeria, which they regarded as their homeland. Moreover, they were criticized and held responsible by French mainlanders for the political, economic, and social troubles that the war had caused to France. Algerian Jews, who feared persecution because of their opposition to Algerian independence, also fled Algeria en masse, with 130,000 Jews leaving for France where they held French citizenship; some 7,000 Jews also immigrated to Israel.

The harkis, or indigenous Algerians who had served in the French Army as regulars or auxiliaries, met a harsher fate. Disarmed after the war by their French military commanders and vilified by Algerians as traitors and French collaborators, the harkis and their families faced harsh retaliation by the FLN and civilian mobs – some 50,000 to 100,000 harkis and their kin were killed, most in grisly circumstances. Some 91,000 harkis and their families did succeed in escaping to France under the aegis of their French commanders in violation of the orders of the French government.

The bitter effects of the war were felt in both countries for many years. Throughout the conflict, France described its actions in Algeria as a “law and order maintenance operation”, and not war. Then in June 1999, thirty-seven years after the war ended, the French government admitted that “war” had indeed taken place in Algeria.