On January 18, 1974, Egypt and Israel signed a Disengagement of Forces Agreement (also known as the Sinai I Agreement) following the Yom Kippur War. The agreement established a buffer zone between Egyptian and Israeli forces that was to be monitored by the United Nations Emergency Force (UNEF). Only a limited amount of armament and forces were allowed inside the buffer zone.

On September 4, 1975, the two sides signed the Sinai Interim Agreement (also known as Sinai II Agreement), where they pledged that conflicts between them “shall not be resolved by military force but by peaceful means.” A further withdrawal was agreed and a bigger UN buffer zone was created.

These agreements paved the way for the Camp David Accords (in Camp David, Maryland), which led to the signing of the Egypt-Israel Peace Treaty on March 26, 1979. This landmark peace treaty ended their state of war and normalized relations, and Egypt became the first Arab state to officially recognize Israel. Diplomatic relations between them came into effect in January 1980, with an exchange of ambassadors the following month. Israel withdrew from the Sinai, which Egypt promised to leave demilitarized. Israeli ships were allowed free passage through the Suez Canal, and Egypt recognized the Strait of Tiran and Gulf of Aqaba as international waterways.

(Taken from Wars of 20th Century – Volume 2)

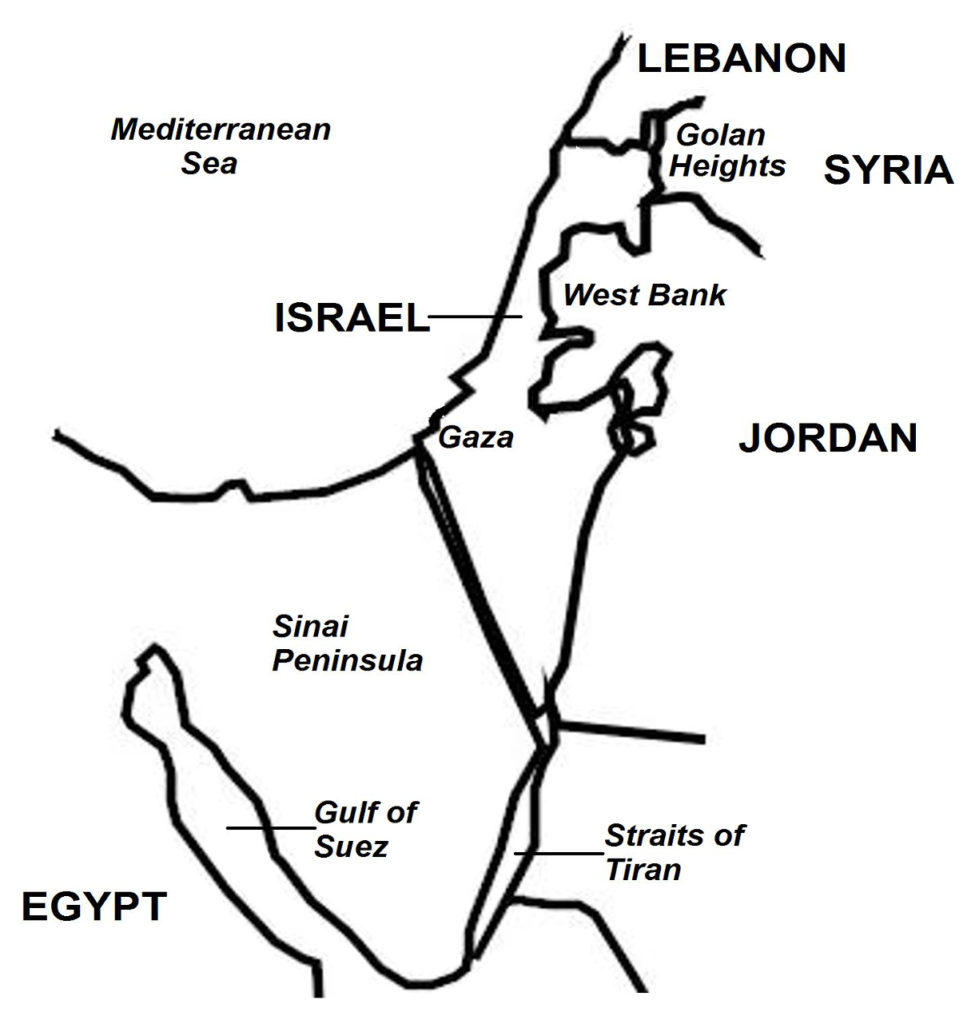

Background of the Yom Kippur War With its decisive victory in the Six-Day War in June 1967, Israel gained control of the Sinai Peninsula and Gaza Strip from Egypt, the Golan Heights from Syria, and the West Bank from Jordan. The Sinai Peninsula and Golan Heights were integral territories of Egypt and Syria, respectively, and both countries were determined to take them back. In September 1967, Egypt and Syria, together with other Arab countries, issued the Khartoum Declaration of the “Three No’s”, that is, no peace, recognition, and negotiations with Israel, which meant that only armed force would be used to win back the lost lands.

Shortly after the Six-Day War ended, Israel offered to return the Sinai Peninsula and Golan Heights in exchange for a peace agreement, but the plan apparently was not received by Egypt and Syria. In October 1967, Israel withdrew the offer.

In the ensuing years after the Six-Day War, Egypt carried out numerous small attacks against Israeli military and government targets in the Sinai. In what is now known as the “War of Attrition”, Egypt was determined to exact a heavy economic and human toll and force Israel to withdraw from the Sinai. By way of retaliation, Israeli forces also launched attacks into Egypt. Armed incidents also took place across Israel’s borders with Syria, Jordan, and Lebanon. Then, as the United States, which backed Israel, and the Soviet Union, which supported the Arab countries, increasingly became involved, the two superpowers prevailed upon Israel and Egypt to agree to a ceasefire in August 1970.

In September 1970, Gamal Abdel Nasser, Egypt’s hard-line president, passed away. Succeeding as Egypt’s head of state was Vice-President Anwar Sadat, who began a dramatic shift in foreign policy toward Israel. Whereas the former regime was staunchly hostile to Israel, President Sadat wanted a diplomatic solution to the Egyptian-Israeli conflict. In secret meetings with U.S. government officials and a United Nations (UN) representative, President Sadat offered a proposal that in exchange for Israel’s return of the Sinai to Egypt, the Egyptian government would sign a peace treaty with Israel and recognize the Jewish state.

However, the Israeli government of Prime Minister Golda Meir refused to negotiate. President Sadat, therefore, decided to use military force. He knew, however, that his armed forces were incapable of dislodging the Israelis from the Sinai. He decided that an Egyptian military victory on the battlefield, however limited, would compel Israel to see the need for negotiations. Egypt began preparations for war. Large amounts of modern weapons were purchased from the Soviet Union. Egypt restructured its large, but ineffective, armed forces into a competent fighting force.

In order to conceal its war plans, Egypt carried out a number of ruses. The Egyptian Army constantly conducted military exercises along the western bank of the Suez Canal, which soon were taken lightly by the Israelis. Egypt’s persistent war rhetoric eventually was regarded by the Israelis as mere bluff. Through press releases, Egypt underreported the true strength of its armed forces. The government also announced maintenance and spare parts problems with its war equipment and the lack of trained personnel to operate sophisticated military hardware. Furthermore, when President Sadat expelled 20,000 Soviet advisers from Egypt in July 1972, Israel believed that the Egyptian Army’s military capability was weakened seriously. In fact, thousands of Soviet personnel remained in Egypt and Soviet arms shipments continued to arrive. Egyptian military planners worked closely and secretly with their Syrian counterparts to devise a simultaneous two-front attack on Israel. Consequently, Syria also secretly mobilized for war.

Israel’s intelligence agencies learned many details of the invasion plan, even the date of the attack itself, October 6. Israel detected the movements of large numbers of Egyptian and Syrian troops, armor, and – in the Suez Canal– bridging equipment. On October 6, a few hours before Egypt and Syria attacked, the Israeli government called for a mobilization of 120,000 soldiers and the entire Israeli Air Force. However, many top Israeli officials continued to believe that Egypt and Syria were incapable of starting a war and that the military movements were just another army exercise. Israeli officials decided against carrying out a pre-emptive air strike (as Israel had done in the Six-Day War) to avoid being seen as the aggressor. Egypt and Syria chose to attack on Yom Kippur (which fell on October 6 in 1973), the holiest day of the Jewish calendar, when most Israeli soldiers were on leave.