On February 29 and March 1, 1992, Bosnia and Herzegovina held a referendum to decide for independence or to remain as a constituent republic within Yugoslavia. The turn-out was 63.4%, of whom 99.7% voted for independence. The voters consisted mainly of Bosniak and Bosnian Croats who favored independence. Bosnian Serbs, who comprised about 30% of the population, largely boycotted the referendum or were prevented from voting by Bosnian Serb authorities.

Following the referendum, on March 3, 1992, Bosnia and Herzegovina declared independence as the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina. On April 7, 1992, the United States and European Economic Community recognized the new state; other countries soon did the same. On May 22, 1992, Bosnia and Herzegovina was admitted to the United Nations.

However, also on April 7, 1992, Bosnian Serbs declared a separate independence as the Republika Srpska, with its Assembly issuing a declaration on May 12, “Six Strategic Goals of the Serbian Nation”, notably, “The first such goal is separation of the two national communities – separation of states, separation from those who are our enemies and who have used every opportunity, especially in this century, to attack us, and who would continue with such practices if we were to stay together in the same state.”.

(Taken from Bosnian War – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 1)

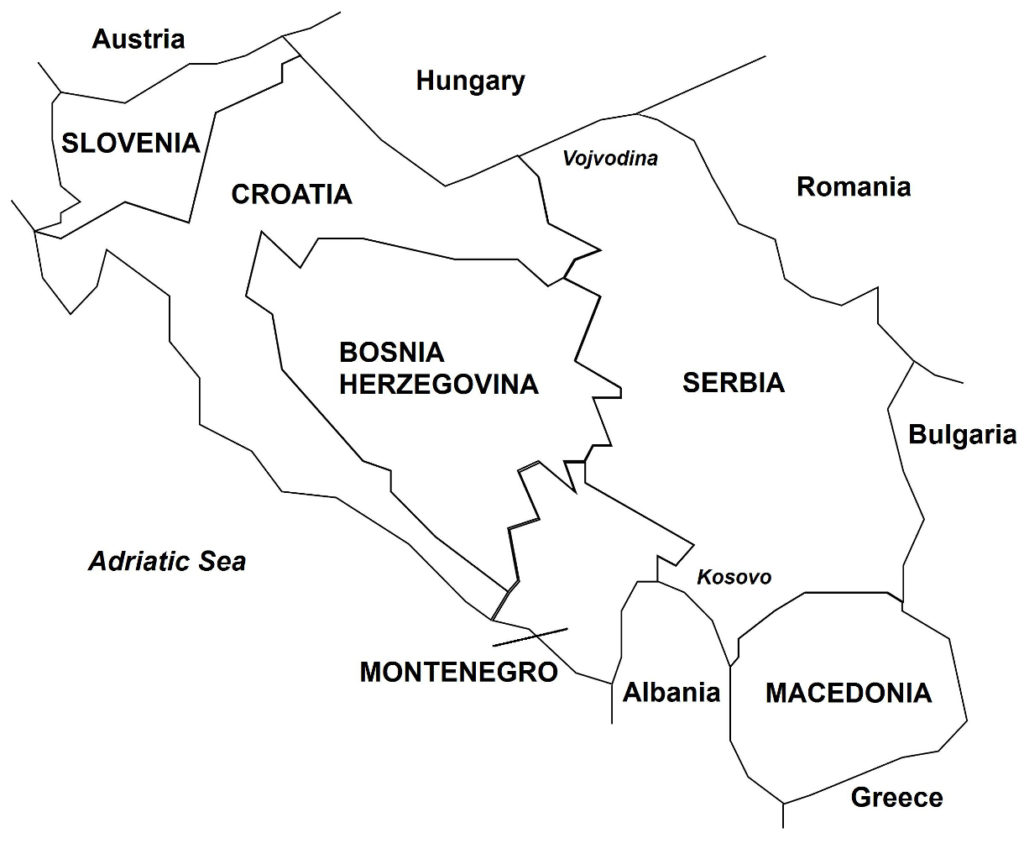

Background Bosnia-Herzegovina has three main ethnic groups: Bosniaks (Bosnian Muslims), comprising 44% of the population, Bosnian Serbs, with 32%, and Bosnian Croats, with 17%. Slovenia and Croatia declared their independences in June 1991. On October 15, 1991, the Bosnian parliament declared the independence of Bosnia-Herzegovina, with Bosnian Serb delegates boycotting the session in protest. Then acting on a request from both the Bosnian parliament and the Bosnian Serb leadership, a European Economic Community arbitration commission gave its opinion, on January 11, 1992, that Bosnia-Herzegovina’s independence cannot be recognized, since no referendum on independence had taken place.

Bosnian Serbs formed a majority in Bosnia’s northern regions. On January 5, 1992, Bosnian Serbs seceded from Bosnia-Herzegovina and established their own country. Bosnian Croats, who also comprised a sizable minority, had earlier (on November 18, 1991) seceded from Bosnia-Herzegovina by declaring their own independence. Bosnia-Herzegovina, therefore, fragmented into three republics, formed along ethnic lines.

Furthermore, in March 1991, Serbia and Croatia, two Yugoslav constituent republics located on either side of Bosnia-Herzegovina, secretly agreed to annex portions of Bosnia-Herzegovina that contained a majority population of ethnic Serbians and ethnic Croatians. This agreement, later re-affirmed by Serbians and Croatians in a second meeting in May 1992, was intended to avoid armed conflict between them. By this time, heightened tensions among the three ethnic groups were leading to open hostilities.

Mediators from Britain and Portugal made a final attempt to avert war, eventually succeeding in convincing Bosniaks, Bosnian Serbs, and Bosnian Croats to agree to share political power in a decentralized government. Just ten days later, however, the Bosnian government reversed its decision and rejected the agreement after taking issue with some of its provisions.

War At any rate, by March 1992, fighting had already broken out when Bosnian Serb forces attacked Bosniak villages in eastern Bosnia. Of the three sides, Bosnian Serbs were the most powerful early in the war, as they were backed by the Yugoslav Army. At their peak, Bosnian Serbs had 150,000 soldiers, 700 tanks, 700 armored personnel carriers, 3,000 artillery pieces, and several aircraft. Many Serbian militias also joined the Bosnian Serb regular forces.

Bosnian Croats, with the support of Croatia, had 150,000 soldiers and 300 tanks. Bosniaks were at a great disadvantage, however, as they were unprepared for war. Although much of Yugoslavia’s war arsenal was stockpiled in Bosnia-Herzegovina, the weapons were held by the Yugoslav Army (which became the Bosnian Serbs’ main fighting force in the early stages of the war). A United Nations (UN) arms embargo on Yugoslavia was devastating to Bosniaks, as they were prohibited from purchasing weapons from foreign sources.

In March and April 1992, the Yugoslav Army and Bosnian Serb forces launched large-scale operations in eastern and northwest Bosnia-Herzegovina. These offensives were so powerful that large sections of Bosniak and Bosnian Croat territories were captured and came under Bosnian Serb control. By the end of 1992, Bosnian Serbs controlled 70% of Bosnia-Herzegovina.

Then under a UN-imposed resolution, the Yugoslav Army was ordered to leave Bosnia-Herzegovina. However, the Yugoslav Army’s withdrawal did not affect seriously the Bosnian Serbs’ military capability, as a great majority of the Yugoslav soldiers in Bosnia-Herzegovina were ethnic Serbs. These soldiers simply joined the ranks of the Bosnian Serb forces and continued fighting, using the same weapons and ammunitions left over by the departing Yugoslav Army.

In mid-1992, a UN force arrived in Bosnia-Herzegovina that was tasked to protect civilians and refugees and to provide humanitarian aid. Fighting between Bosniaks and Bosnian Croats occurred in Herzegovina (the southern regions) and central Bosnia, mostly in areas where Bosnian Muslims formed a civilian majority. Bosnian Croat forces held the initiative, conducting offensives in Novi Travnik and Prozor. Intense artillery shelling reduced Gornji Vakuf to rubble; surrounding Bosniak villages also were taken, resulting in many civilian casualties.

In May 1992, the Lasva Valley came under attack from the Bosnian Croat forces who, for 11 months, subjected the region to intense artillery shelling and ground attacks that claimed the lives of 2,000 mostly civilian casualties. The city of Mostar, divided into Muslim and Croat sectors, was the scene of bitter fighting, heavy artillery bombardment, and widespread destruction that resulted in thousands of civilian deaths. Numerous atrocities were committed in Mostar.

By July 1993, however, Bosniaks had formed a relatively competent military force that was armed with weapons produced from a rapidly growing local arms-manufacturing industry. Bosniaks, therefore, were better able to defend their territories, and even launch some of their own limited offensive operations.

Then in early 1994, with another Bosnian Serb general offensive looming, Bosniaks and Bosnian Croats found common ground. With the urging of the United States, on February 23, 1994, Bosniaks and Bosnian Croats formed a unified government under the “Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina”. The civil war shifted to fighting between the combined Bosniak-Bosnian Croat forces against the Bosnian Serb Army.

In early 1994, Bosnian Serb forces laid siege to Sarajevo, Bosnia’s capital, relentlessly pounding the city with heavy artillery and inflicting heavy civilian casualties. The siege of the capital drew international condemnation, with the UN and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) becoming increasingly involved in the war. NATO declared Bosnia-Herzegovina a no-fly zone. On February 28, 1994, NATO warplanes downed four Serbian aircraft over Banja Luka.

Under a UN threat of a NATO airstrike, Bosnian Serbs were forced to lift the siege on Maglaj; supply convoys thus were able to reach the city by land, the first time in nearly ten months. In April 1994, NATO warplanes attacked Bosnian Serb forces that were threatening a UN-protected area in Gorazde. Later that month, a Danish contingent of the UN forces engaged Bosnian Serb Army units in the village of Kalesija. The NATO air strikes, which greatly contributed to ending the war, were conducted in coordination with the UN humanitarian and peacekeeping forces in Bosnia-Herzegovina.

With the US lifting its arms embargo on Bosnia-Herzegovina in November 1994, Bosniak forces began to receive shipments of American weapons. The UN was also alarmed at the increasing reports of atrocities being committed by Bosnian Serb forces. After Bosnian Serb artillery attacks killed 37 persons and 90 others in Sarajevo in August 1995, NATO launched a large airstrike on Bosnian Serb Army positions. Between August 30 and September 14, four hundred NATO planes launched thousands of attacks against key Bosnian Serb military units and installations in Sarajevo, Pale, Lisina, and other sites.

Meanwhile, starting in the summer of 1995, Bosnian Croat and Bosniak armies had begun to take the initiative in the ground war against the Bosnian Serbs. The combined allied armies launched a series of offensives against Bosnian Serbs in western Bosnia. By the end of July, the allies had captured 1,600 square kilometers of territory. In the Krajina region, a massive Bosnian Croat-Bosniak offensive involving 170,000 soldiers, 250 tanks, 500 artillery pieces, and 40 planes overwhelmed the Bosnian Serb forces of 30,000 troops, 300 tanks, 200 armored carriers, 560 artillery pieces, 135 anti-aircraft guns, and 25 planes.

By October 12, Bosnian Serb-held Banja Luka was in sight. The Bosnian Croat-Bosniak offensives had captured western Bosnia and 51% of the country, and threatened to advance further east. By this time, Bosnian Serb forces were on the brink of defeat.

Representatives from the three ethnic groups now met to negotiate an end to the war. On September 14, NATO ended its air strikes against Bosnian Serb forces. By month’s end, fighting was winding down in most sectors.

On November 21, 1995, high-level government officials from Bosnia-Herzegovina, Serbia, and Croatia signed a peace agreement, bringing the war to an end. The reconstruction of the war-ravaged country soon began.

Many atrocities and human rights violations were committed in the war, the great majority of which were perpetrated by Bosnian Serbs, but also by Bosnian Croats, and to a much lesser extent, by Bosniaks.

The International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia (ICTY), established by the UN to prosecute war crimes, determined that Bosnian Serb atrocities committed in the town of Srebrenica, where 8,000 civilians were killed, constituted a genocide. Other atrocities, such as the killing and wounding of over one hundred residents in Markale on February 5, 1994 and August 28, 1995 resulting from the Serbian mortar shelling of Sarajevo, have been declared by the ICTY as ethnic cleansing (a war crime less severe than genocide).

Bosnian Croat forces also perpetrated many atrocities, including those that occurred in the Lasva Valley, which caused the deaths and forced disappearances of 2,000 Bosniaks, as well as other violent acts against civilians. Bosniak forces also committed crimes against civilians and captured soldiers, but these were of much less frequency and severity.

About 90% of all crimes in the Bosnian War were attributed to Bosnian Serbs. The ICTY has convicted and meted out punishments to many perpetrators, who generally were military commanders and high-ranking government officials. The war caused some 100,000 deaths, both civilian and military; over two million persons were displaced by the fighting.

After the war, Bosnia-Herzegovina retained its territorial integrity. As a direct consequence of the war, Bosnia-Herzegovina established a decentralized government composed of two political and geographical entities: the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina (consisting of Bosniak and Bosnian Croat majorities) and the Republic of Srpska (consisting of Bosnian Serbs). The president of Bosnian-Herzegovina is elected on rotation, with a Bosniak, Bosnian Croat, and Bosnian Serb taking turns as the country’s head of state.