On February 26, 1976, Spain fully withdrew from Spanish Sahara, which henceforth became universally called Western Sahara (although the UN already had referred to it as such by 1975). As per the agreement, Moroccan forces occupied their designated region (which Morocco soon called its Southern Provinces; also in 1979, Morocco would include the southern zone after Mauritania withdrew); and Mauritanian troops occupied Titchla, La Guera, and later Dakhla (as the capital), of its newly designated Saharan province of Tiris al-Gharbiyya. Then on April 14, 1976, the two countries signed an agreement that formally divided the territory into their respective zones of occupation and control.

In the three-month period (November 1975–February 1976) during Spain’s withdrawal and replacement with Moroccan and Mauritanian administrations, tens of thousands of Sahrawis fled to the Saharan desert, and subsequently into Tindouf, Algeria. On February 27, 1976, one day after Spain withdrew from the territory, the Polisario Front declared the founding of the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR), with a government-in-exile based in Algeria.

(Taken from Western Sahara War – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 4)

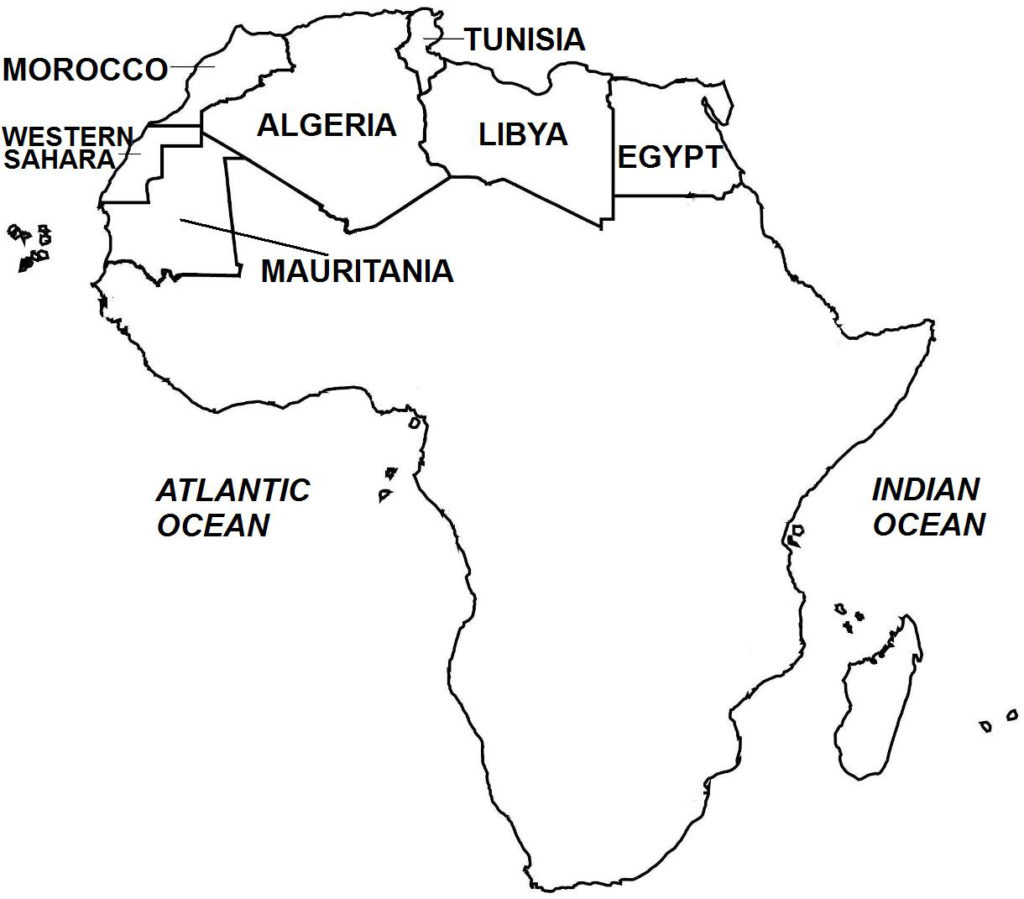

Background On December 3, 1974, the UNGA passed Resolution 3292 declaring the UN’s interest in evaluating the political aspirations of Sahrawis in the Spanish territory. For this purpose, the UN formed the UN Decolonization Committee, which in May – June 1975, carried out a fact-finding mission in Spanish Sahara as well as in Morocco, Mauritania, and Algeria. In its final report to the UN on October 15, 1978, the Committee found broad support for annexation among the general population in Morocco and Mauritania. In Spanish Sahara, however, the Sahrawi people overwhelmingly supported independence under the leadership of the Polisario Front, while Spain-backed PUNS did not enjoy such support. In Algeria, the UN Committee found strong support for the Sahrawis’ right of self-determination.

Algeria previously had shown little interest in the Polisario Front and, in an Arab League summit held in October 1974, even backed the territorial ambitions of Morocco and Mauritania. But by summer of 1975, Algeria was openly defending the Polisario Front’s struggle for independence, a support that later would include military and economic aid and would have a crucial effect in the coming war.

Meanwhile, King Hassan II, the Moroccan monarch (son of King Mohammed V, who had passed away in 1961) actively sought to pursue its claim and asked Spain to postpone holding the referendum; in January 1975, the Spanish government granted the Moroccan request. In June 1975, the Moroccan government pressed the UN to raise the Saharan issue to the International Court of Justice (ICJ), the UN’s primary judicial agency. On October 16, 1975, one day after the UN Decolonization Committee report was released, the ICJ issued its decision, which consisted of the following four important points (the court refers to Spanish Sahara as Western Sahara):

1. At the time of Spanish colonization, “there were legal ties between this territory and the Kingdom of Morocco”;

2. At the time of Spanish colonization, “there were legal ties between this territory and the Mauritanian entity”;

3. There existed “at the time of Spanish colonization … legal ties of allegiance between the Sultan of Morocco and some of the tribes living in the territory of Western Sahara. They equally show the existence of rights, including some rights relating to the land, which constituted legal ties between the Mauritanian entity… and the territory of Western Sahara”;

4. The ICJ concluded that the evidences presented “do not establish any tie of territorial sovereignty between the territory of Western Sahara and the Kingdom of Morocco or the Mauritanian entity. Thus, the Court has not found legal ties of such a nature as might affect… the decolonization of Western Sahara and, in particular, … the principle of self-determination through the free and genuine expression of the will of the peoples of the Territory”.

Far from clarifying the issue, the ICJ’s involvement radicalized the parties involved, as each side focused on that part of the court’s decision that vindicated its claims. Morocco and Mauritania cited “legal ties” as supporting their respective claims, while the Polisario Front and Algeria pointed to “do not establish any tie of territorial sovereignty” and “the principle of self-determination through the free and genuine expression of the will of the peoples of the Territory” to put forward the Sahrawi peoples’ right of self- government. Spain’s chances of influencing the post-colonial Saharan territory began to wane. On September 9, 1975, Spanish foreign minister Pedro Cortina y Mauri and Polisario Front leader El-Ouali Mustapha Sayed met in Algiers, Algeria to negotiate the transfer of Saharan authority to the Polisario Front in exchange for economic concessions to Spain, particularly in the phosphate and fishing resources in the region. Further meetings were held in Mahbes, Spanish Sahara on October 22. Ultimately, these negotiations did not prosper, as they became sidelined by the accelerating conflict and greater pressures exerted by the other competing parties.

Shortly after the ICJ decision was released, King Hassan II announced that Morocco would hold the “Green March”, set for November 6, 1975, and called on Moroccans to march to and occupy Spanish Sahara. On that date, the Green March (the color green symbolizing Islam) was carried out, with some 350,000 Moroccan civilians, protected by 20,000 soldiers, crossed the border from Tarfaya in southern Morocco and occupied some border regions in northern Spanish Sahara. Under instructions from the Spanish central government in Madrid, Spanish troops did not resist the incursion. On November 9, the marchers returned to Morocco, on orders of King Hassan II who declared the action a success.

On October 31, 1975, six days before the Green March began, units of the Moroccan Army entered Farsia, Haousa and Jdiriya in northeast Saharan territory to deter Algerian intervention. Spain had protested the Moroccan action to the UN in a futile attempt to have the international body stop the march; instead, the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) passed Resolution 380 that deplored the march and called on Morocco to withdraw from the territory.

The timing of the escalating crisis could not have come at a worse time for Spain. In late October 1975, General Francisco Franco, Spain’s dictator, was terminally ill and soon passed away on November 20, 1975. In the period before and after his death, Spain underwent great political uncertainty, as the sudden void left by General Franco, who had ruled for 40 years, threatened to ignite a political power struggle. The tenuous government, now led by King Juan Carlos as head of state, was unwilling to face a potentially ruinous war. World-wide colonialism was at its twilight– just one year earlier, Portugal, one of the last colonial powers, had agreed to end its long colonial wars against African nationalist movements, eventually leading to the independences in 1975 of its African possessions of Angola, Mozambique, Portuguese Guinea (since 1973), Cape Verde, and São Tomé and Príncipe.

By late October 1975, Spanish officials had begun to hold clandestine meetings in Madrid with representatives from Morocco and Mauritania. As a precaution for war, in early November 1975, Spain carried out a forced evacuation of Spanish nationals from the territory. On November 12, further negotiations were held in the Spanish capital, culminating two days later (November 14) in the signing of the Madrid Accords, where Spain ceded the administration (but not sovereignty) of the territory, with Morocco acquiring the regions of El-Aaiún, Boujdour, and Smara, or the northern two-thirds of the region; while Mauritania the Dakhla (formerly Villa Cisneros) region, or the southern third; in exchange for Spain acquiring 35% of profits from the territory’s phosphate mining industry as well as off-shore fishing rights. Joint administration by the three parties through an interim government (led by the territory’s Spanish Governor-General) was undertaken in the transitional period for full transfer to the new Moroccan and Mauritanian authorities. (The Madrid Accords was not, and also since has not, been recognized by the UN, which officially continued to regard Spain as the “de jure”, if not “de facto”, administrative authority over the territory; furthermore, the UN deems the conflict region as occupied territory by Morocco and, until 1979, also by Mauritania.)

On February 26, 1976, Spain fully withdrew from the territory, which henceforth became universally called Western Sahara (although the UN already had referred to it as such by 1975). As per the agreement, Moroccan forces occupied their designated region (which Morocco soon called its Southern Provinces; also in 1979, Morocco would include the southern zone after Mauritania withdrew); and Mauritanian troops occupied Titchla, La Guera, and later Dakhla (as the capital), of its newly designated Saharan province of Tiris al-Gharbiyya. Then on April 14, 1976, the two countries signed an agreement that formally divided the territory into their respective zones of occupation and control.

In the three-month period (November 1975–February 1976) during Spain’s withdrawal and replacement with Moroccan and Mauritanian administrations, tens of thousands of Sahrawis fled to the Saharan desert, and subsequently into Tindouf, Algeria. On February 27, 1976, one day after Spain withdrew from the territory, the Polisario Front declared the founding of the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR), with a government-in-exile based in Algeria.