On February 22, 1999, the Ethiopian Army, supported by air, armored, and artillery units, launched a major offensive in the eastern front. Five days later, the Ethiopians had broken through and captured the Badme area, and had advanced 10 kilometers into Eritrea. The Eritrean government then announced that it was ready to accept the OAU peace plan, but Ethiopia, which earlier had also agreed to the proposal, now demanded that Eritrea withdraw all its forces from Ethiopian territory before the plan could be implemented.

(Taken from Ethiopian-Eritrean War – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 4)

Background In the midst of Eritrea’s independence war, in 1974, Emperor Haile Selassie was deposed in a military coup and a council of army officers called “Derg” came to power. The Derg regime experienced great political upheavals initially arising from internal power struggles, as well as the Eritrean insurgency and other ethnic-based armed rebellions; in 1977-78, the Derg also was involved in a war with neighboring Somalia (the Ogaden War, separate article).

By the early 1990s, the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF), a coalition of Ethiopian rebel groups, had formed a military alliance with the EPLF and separately accelerated their insurgencies against the Derg regime. In May 1991, the EPRDF toppled the Derg regime, while the EPLF seized control of Eritrea by defeating and expelling Ethiopian government forces. Both the EPRDF and EPLF then gained power in Ethiopia and Eritrea, respectively, with these rebel movements transitioning into political parties. Under a UN-facilitated process and with the Ethiopian government’s approval, Eritrea officially seceded from Ethiopia and, following a referendum where nearly 100% of Eritreans voted for independence, achieved statehood as a fully sovereign state.

Because of their war-time military alliance, the governments of Ethiopia and Eritrea maintained a close relationship and signed an Agreement of Friendship of Cooperation that envisioned a comprehensive package of mutually beneficial political, economic, and social joint endeavors; subsequent treaties were made in the hope of integrating the two countries in a broad range of other fields.

Both states nominally were democracies but with strong authoritarian leaders, Prime Minister Meles Zenawi in Ethiopia and President Isaias Afwerki in Eritrea. State and political structures differed, however, with Ethiopia establishing an ethnic-based multi-party federal parliamentary system and Eritrea setting up a staunchly nationalistic, one-party unitary system. Eritrea also maintained a strong militaristic culture, acquired from its long independence struggle, for which in the years after gaining independence, it came into conflict with its neighbors, i.e. Yemen, Djibouti, and Sudan.

Ethiopian-Eritrean relations soon also deteriorated as a result of political differences, as well as the personal rivalry between the two countries’ leaders. Furthermore, during their revolutionary struggles, the Eritrean and Ethiopian rebel groups sometimes came into direct conflict over projecting power and controlling territory, which was overcome only by their mutual need to defeat a common enemy. In the post-war period, this acrimonious historical past now took on greater significance. Relations turned for the worse when in November 1997, Eritrea introduced its own currency, the “nakfa” (which replaced the Ethiopian birr), in order to steer its own independent local and foreign economic and trade policies. During the post-war period, trade between Ethiopia and Eritrea was significant, and Eritrea gave special privileges to the now landlocked Ethiopia to use the port of Assab for Ethiopian maritime trade. But with Eritrea introducing its own currency, Ethiopia banned the use of the nakfa in all but the smallest transactions, causing trade between the two states to plummet. Trucks carrying goods soon were backed up at the border crossings and the two sides now saw the need to delineate the as yet unmarked border to control cross-border trade.

Meanwhile, disputes in the frontier region in and around the town of Badme had experienced a steady increase. As early as 1992, Eritrean regional officials complained that Ethiopian armed bands descended on Eritrean villages, and expelled Eritrean residents and destroyed their homes. In July 1994, regional Ethiopian and Eritrean representatives met to discuss the matter, but harassments, expulsions, and arrests of Eritreans continued to be reported in 1994-1996. Then in April 1994, the Eritrean government became aware that Ethiopia had carried out a number of demarcations along the Badme area, prompting an exchange of letters by Prime Minister Zenawi and President Afwerki. In November 1994, a joint panel was set up by the two sides to try and resolve the matter; however, this effort made no substantial progress. In the midst of the Badme affair, another crisis broke out in July-August 1997 where Ethiopian troops entered another undemarcated frontier area in pursuit of the insurgent group ARDUF (Afar Revolutionary Democratic Unity Front or Afar Revolutionary Democratic Union Front); then when Ethiopia set up a local administration in the area, Eritrea protested, leading to firefights between Ethiopian and Eritrean forces.

Another source of friction between the two countries was generated when, starting in 1993, the regional administration in Tigray Province (in northern Ethiopia) published “administrative and fiscal” maps of Tigray that included the Badme area and a number of Eritrean villages that lay beyond the 1902 colonial-era and de facto “border” line. Since the 1950s, Tigray had administered this area and had established settlements there. In turn, Eritrea declared that the area had been encroached as it formed part of the Eritrean Gash-Barka region.

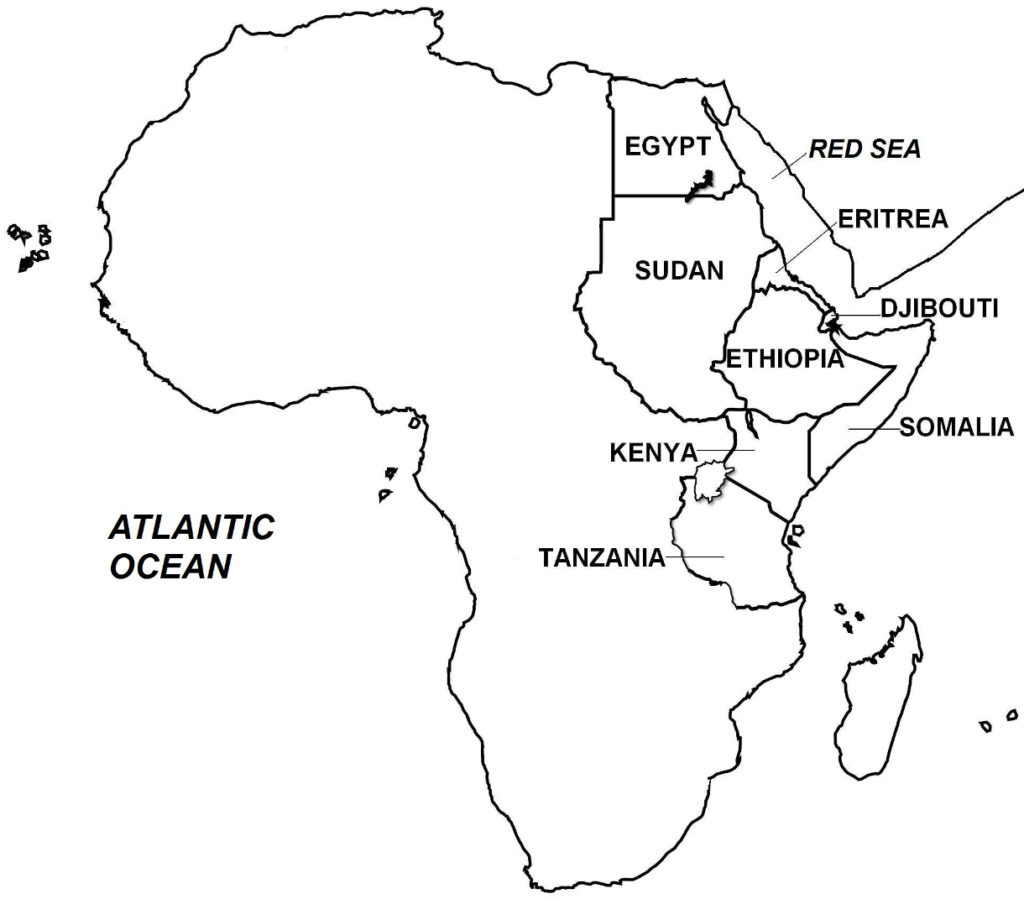

Badme, a 160-square mile area that became the trigger for the coming war, was located in the wider Badme plains, the latter forming a section of the vast semi-desert lowlands adjoining the Ethiopian mountains and stretching west to the Sudan. During the early 20th century when the Ethiopian-Italian border treaties were made, Badme was virtually uninhabited, save for the local endemic Kunama tribal people. The 1902 treaty, which became the de facto border between the Ethiopian Empire and Italian Eritrea in the western and central regions, stipulated that the border, heading from west to east, ran starting from Khor Um Hagger in the Sudanese border, followed the Tekezze (Setit) River to its confluence with the Maieteb River, at which point it ran a straight line north to where the Mareb River converges with the Ambessa River (Figure 32). Thereafter, the border followed a general eastward direction along the Mareb, through the smaller Melessa River, and finally along the Muna River. In turn, the 1908 treaty specified that the border along the eastern regions would follow the outlines of the Red Sea coastline from a distance of 60 kilometers inland. These treaties have since been upheld by successive Ethiopian governments, whose maps have followed the treaties’ delineations to form a border that is otherwise unmarked on the ground.