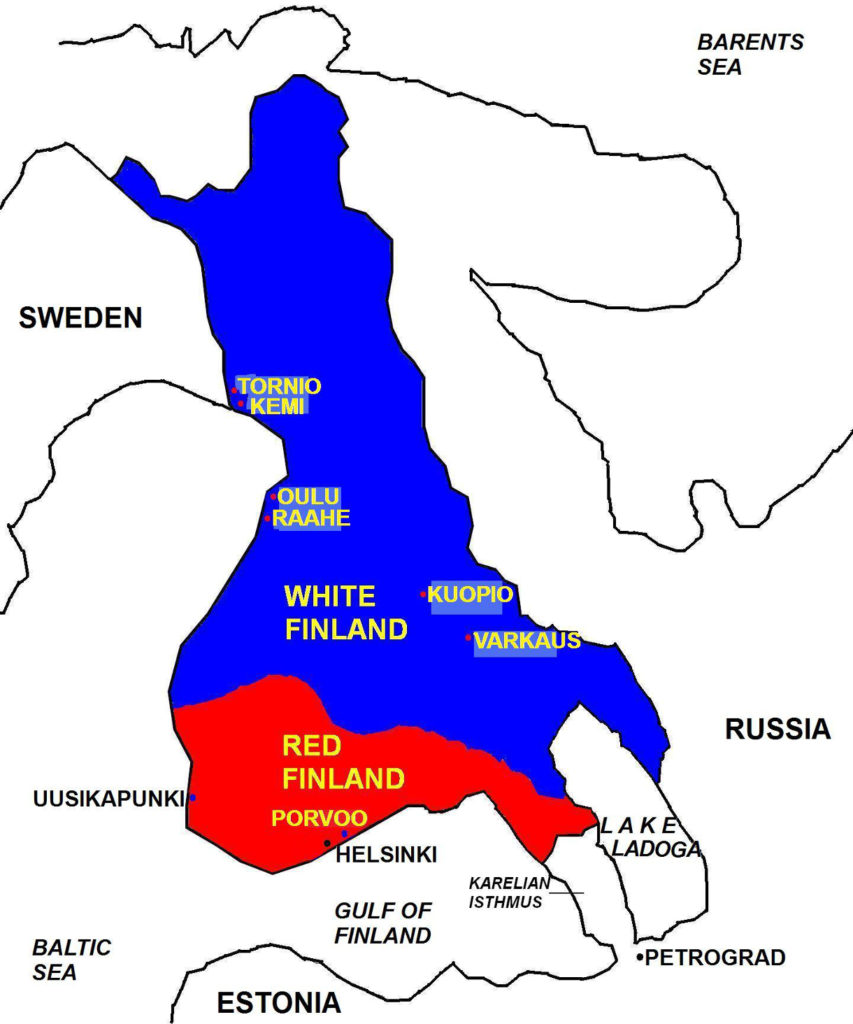

The February 1918 German offensive had major repercussions for Finland, as the German-Russian rivalry in World War I spilled over into Finland and soon merged with the Finnish Civil War. Germany had backed White Finland by providing weapons and sending Finnish Jäger soldiers to provide training for the Finnish (White) Army in order to undermine Soviet Russia, which supported socialist Red Finland. But following a request by the White government on February 14, 1918 for direct assistance, on March 5, 1918 Germany intervened by landing advance units on Åland Islands in preparation to an amphibious landing on the Finnish mainland.

Just as Germany’s involvement increased, Soviet Russia, complying with the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, withdrew its remaining forces in Finland. By the end of March 1918, the Finnish Civil War had turned invariably in favor of the White forces, brought about also by other reasons: General Mannerheim proved to be a proficient commander; the Jäger and Swedish officers had raised the competence and morale of the Finnish (White) Army; and modern German weapons were arriving in greater quantities. Meanwhile, the Red Guards, already weakened by the withdrawal of the Russian Army, also suffered from a chronic lack of capable military and political leadership, inadequate training, and weapons shortages. Furthermore, Red Guard field officers were voted into their positions by consensus among rank-and-field soldiers (rather than competence), which compromised discipline and reduced resoluteness in battle.

(Taken from Finnish Civil War – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 4)

Aftermath of the Finnish Civil War In May 1918, the victorious conservative government returned its capital to Helsinki. Because of the German Army’s contribution to the military success and under the terms of the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, Finland came under Germany’s sphere of influence, much like the other Russian territories ceded to Germany, i.e. Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Belarus, Ukraine, and Russian Poland. Finnish-German relations drew even closer with the signing of bilateral military and economic agreements. In October 1918, German hegemony was furthered when the Finnish Parliament, dominated by monarchists, named a German Prince, Friedrich Karl, as King of Finland.

However, the Western Front of World War I was still being fought. After a failed German offensive in March 1918, the Allies counterattacked, pushing back the German Army all across the front. By November 1918, the German Empire verged on total collapse, both from defeat on the battlefield and by political and social unrest caused by the outbreak of the German Revolution. On November 9, 1918, the German monarchy ended when Kaiser Wilhelm II abdicated the throne; an interim government (which soon turned Germany into a republic) signed the Compiègne Armistice on November 11, 1918, ending World War I.

In the aftermath, Germany was forced to relinquish its authority over Eastern Europe, including Finland. In mid-December 1916, with the departure of the German Army from Finland, the Finnish parliament’s plan to install a monarchy with a German prince fell apart. Finland held local elections in December 1918, and parliamentary elections in March 1919, paving the way for the establishment of a republic, which officially came into existence with the ratification of the Finnish constitution in July 1919. Also in July, Finland’s first president, Kaarlo Juho Ståhlberg, was elected into office.

Earlier in May 1919, the United States and Britain recognized Finland’s independence; other countries, including Denmark, Norway, Sweden, Switzerland, and Greece already had recognized Finland’s sovereignty a few months earlier. On October 14, 1920, Finland and Soviet Russia formally ended hostilities in the Treaty of Tartu (in Tartu, Estonia) that also established a common Finnish-Russian border.

The civil war left a lasting, bitter legacy in Finland. The widespread violence perpetrated by both sides of the war aggravated the already socially divided Finland, as nearly every Finn was affected directly or indirectly. This polarization led to non-compromise and encouraged radicalization of elements of the right and left, into fascists and communists, respectively, in the following years. Ultimately, however, political moderation prevailed, allowing Finland to emerge united politically, socially, and economically. Furthermore, in the 1930s, the country experienced high economic growth, with traditional industries growing and new ones emerging. Agricultural reforms also transformed the countryside – by the 1930s, some 90% of previously landless farmers owned their farmlands. Also in the 1930s, the growing threats from Germany and the Soviet Union further bound Finns toward nationalist unity.