On December 14, 1972, the U.S. government issued a 72-hour ultimatum to North Vietnam to return to negotiations. On the same day, U.S. planes air-dropped naval mines off the North Vietnamese waters, again sealing off the coast to sea traffic. Then on President Nixon’s orders to use “maximum effort…maximum destruction”, on December 18-29, 1972, U.S. B-52 bombers and other aircraft under Operation Linebacker II, launched massive bombing attacks on targets in North Vietnam, including Hanoi and Haiphong, hitting airfields, air defense systems, naval bases, and other military facilities, industrial complexes and supply depots, and transport facilities. As many of the restrictions from previous air campaigns were lifted, the round-the-clock bombing attacks destroyed North Vietnam’s war-related logistical and support capabilities. Several B-52s were shot down in the first days of the operation, but changes to attack methods and the use of electronic and mechanical countermeasures greatly reduced air losses. By the end of the bombing campaign, few targets of military value remained in North Vietnam, enemy anti-aircraft guns had been silenced, and North Vietnam was forced to return to negotiations. On January 15, 1973, President Nixon ended the bombing operations.

One week later, on January 23, negotiations resumed, leading four days later, on January 27, 1973, to the signing by representatives from North Vietnam, South Vietnam, the Viet Cong/NLF through its Provisional Revolutionary Government (PRG), and the United States of the Paris Peace Accords (officially titled: “Agreement on Ending the War and Restoring Peace in Vietnam”), which (ostensibly) marked the end of the war. The Accords stipulated a ceasefire; the release and exchange of prisoners of war; the withdrawal of all American and other non-Vietnamese troops from Vietnam within 60 days; for South Vietnam: a political settlement between the government and the PRG to determine the country’s political future; and for Vietnam: a gradual, peaceful reunification of North Vietnam and South Vietnam. As in the 1954 Geneva Accords (which ended the First Indochina War), the DMZ did not constitute a political/territorial border. Furthermore, the 200,000 North Vietnamese troops occupying territories in South Vietnam were allowed to remain in place.

(Taken from Vietnam War – Wars of the 20th Century – Twenty Wars in Asia)

To assuage South Vietnam’s concerns regarding the last two points, on March 15, 1973, President Nixon assured President Thieu of direct U.S. military air intervention in case North Vietnam violated the Accords. Furthermore, just before the Accords came into effect, the United States delivered a large amount of military hardware and financial assistance to South Vietnam.

By March 29, 1973, nearly all American and other allied troops had departed, and only a small contingent of U.S. Marines and advisors remained. A peacekeeping force, called the International Commission of Control and Supervision (ICCS), arrived in South Vietnam to monitor and enforce the Accords’ provisions. But as large-scale fighting restarted soon thereafter, the ICCS became powerless and failed to achieve its objectives.

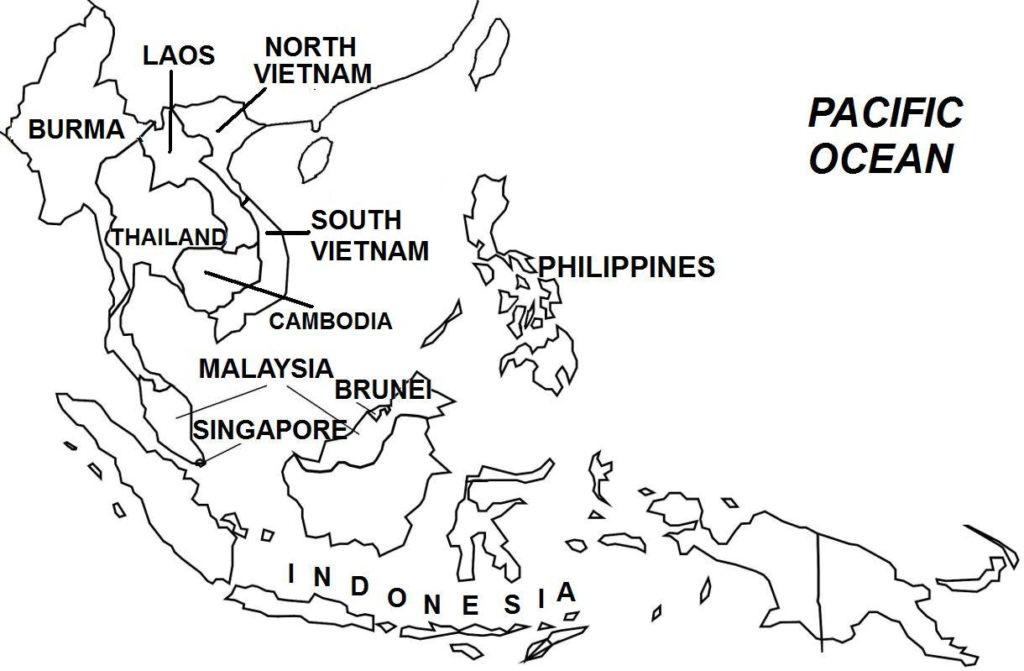

For the United States, the Paris Peace Accords meant the end of the war, a view that was not shared by the other belligerents, as fighting resumed, with the ICCS recording 18,000 ceasefire violations between January-July 1973. President Nixon had also compelled President Thieu to agree to the Paris Peace Accords under threat that the United States would end all military and financial aid to South Vietnam, and that the U.S. government would sign the Accords even without South Vietnam’s concurrence. Ostensibly, President Nixon could fulfill his promise of continuing to provide military support to South Vietnam, as he had been re-elected in a landslide victory in the recently concluded November 1972 presidential election. However, U.S. Congress, which was now dominated by anti-war legislators, did not bode well for South Vietnam. In June 1973, U.S. Congress passed legislation that prohibited U.S. combat activities in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia, without prior legislative approval. Also that year, U.S. Congress cut military assistance to South Vietnam by 50%. Despite the clear shift in U.S. policy, South Vietnam continued to believe the U.S. government would keep its commitment to provide military assistance.

Then in October 1973, a four-fold increase in world oil prices led to a global recession following the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) imposing an oil embargo in response to U.S. support for Israel in the Yom Kippur War. South Vietnam’s economy was already reeling because of the U.S. troop withdrawal (a vibrant local goods and services economy had existed in Saigon because of the presence of large numbers of American soldiers) and reduced U.S. assistance. South Vietnam experienced soaring inflation, high unemployment, and a refugee problem, with hundreds of thousands of people fleeing to the cities to escape the fighting in the countryside.

The economic downturn also destabilized the South Vietnamese forces, for although they possessed vast quantities of military hardware (for example, having three times more artillery pieces and two times more tanks and armor than North Vietnam), budget cuts, lack of spare parts, and fuel shortages meant that much of this equipment could not be used. Later, even the number of bullets allotted to soldiers was rationed. Compounding matters were the endemic corruption, favoritism, ineptitude, and lethargy prevalent in the South Vietnamese government and military.

In the post-Accords period, South Vietnam was determined to regain control of lost territory, and in a number of offensives in 1973-1974, it succeeded in seizing some communist-held areas, but paid a high price in personnel and weaponry. At the same time, North Vietnam was intent on achieving a complete military victory. But since the North Vietnamese forces had suffered extensive losses in the previous years, the Hanoi government concentrated on first rebuilding its forces for a planned full-scale offensive of South Vietnam, planned for 1976.

In March 1974, North Vietnam launched a series of “strategic raids” from the captured territories that it held in South Vietnam. By November 1974, North Vietnam’s control had extended eastward from the north nearly to the south of the country. As well, North Vietnamese forces now threatened a number of coastal centers, including Da Nang, Quang Ngai, and Qui Nhon, as well as Saigon. Expanding its occupied areas in South Vietnam also allowed North Vietnam to shift its logistical system (the Ho Chi Minh Trail) from eastern Laos and Cambodia to inside South Vietnam itself. By October 1974, with major road improvements completed, the Trail system was a fully truckable highway from north to south, and greater numbers of North Vietnamese units, weapons, and supplies were being transported each month to South Vietnam.

North Vietnam’s “strategic raids” also were meant to gauge U.S. military response. None occurred, as at this time, the United States was reeling from the Watergate Scandal, which led to President Nixon resigning from office on August 9, 1974. Vice-President Gerald Ford succeeded as President.

Encouraged by this success, in December 1974, North Vietnamese forces in eastern Cambodia attacked Phuoc Long Province, taking its capital Phuoc Binh in early January 1975 and sending pandemonium in South Vietnam, but again producing no military response from the United States. President Ford had asked U.S. Congress for military support for South Vietnam, but was refused.