On December 16, 1944, the Wehrmacht launched its Ardennes counter-offensive, codenamed “Operation Watch on the Rhine” (German: Unternehmen Wacht am Rhein), which involved 400,000 troops, 12,000 tanks, and 4,200 artillery pieces that had been brought up in utmost secrecy and had escaped Allied intelligence detection. Spearheaded by panzer units, the Germans advanced rapidly to a distance of some 50 miles (80 km) to come within 10 miles (16 km) of the Meuse River. The attack took the defending U.S. 1st Army completely by surprise. Overcast weather also greatly aided the German advance, as Allied planes, which controlled the skies over the battlefield, were unable to launch counter-attacks in the heavy cloud cover. The German penetration produced a salient, which the Allies called a “bulge” in their lines, leading to the Ardennes fighting being popularly called by Allied historians as the “Battle of the Bulge”.

The Allies quickly rallied and reorganized, and stopped the German advance in the north at Elsenborn Ridge and in the south at Bastogne. German attempts to flank Bastogne also were stopped by increasing numbers of Allied forces being brought into the battle. The German crossing of the Meuse River, which was the key to the advance to Antwerp, also failed, as the British held onto the bridges at Dinant, Givet, and Namur. Aside from fierce Allied resistance, the Germans began encountering supply problems, and many of their tanks ground to a halt because of fuel shortages. Then on December 23, 1944, improved weather conditions allowed the Allies to launch air attacks on German units and supply columns. By December 24, the German offensive had effectively stalled. Massing Allied armor bottled up the German tanks, threatening the latter with encirclement.

On January 1, 1945, the Germans launched a new offensive, Operation North Wind, this time directed at the Alsace-Lorraine region to the south, and surprised U.S. 6th Army Group which had been stretched thin in support of the Ardennes battle to the north. The German attack, aimed at recapturing Strasbourg, initially achieved some success, inflicting heavy casualties on the American defenders, but soon sputtered from supply shortages, particularly fuel for the tanks.

On January 3, 1945, the Allies launched a counter-attack after a two-day delay, with U.S. 1st and 3rd Armies executing a pincers movement aimed at eliminating the salient and trapping the Germans inside the pocket. The delay allowed most German units to escape, and on January 7, Hitler finally acquiesced to his commanders and ordered a general withdrawal. Fighting continued until January 25, with the Germans conducting a fighting retreat, in the process also being forced to abandon most of their tanks after running out of fuel, and the Allies retaking lost territory and eliminating the salient. In February 1945, the Allies captured the Hurtgen Forest, finally breaching the Siegfried Line there. For Hitler, the Ardennes counter-offensive was a strategic and costly failure, as Germany lost most of its manpower reserves and armored resources in the West in an ambitious gamble. At the outset, the German High Command gave little chance for the Ardennes offensive to succeed. Its failure also severely weakened German strength on the Western Front against the Allied offensive later that year.

(Taken from Defeat of Germany in the West: 1944-1945 – Wars of the 20th Century – World War II in Europe)

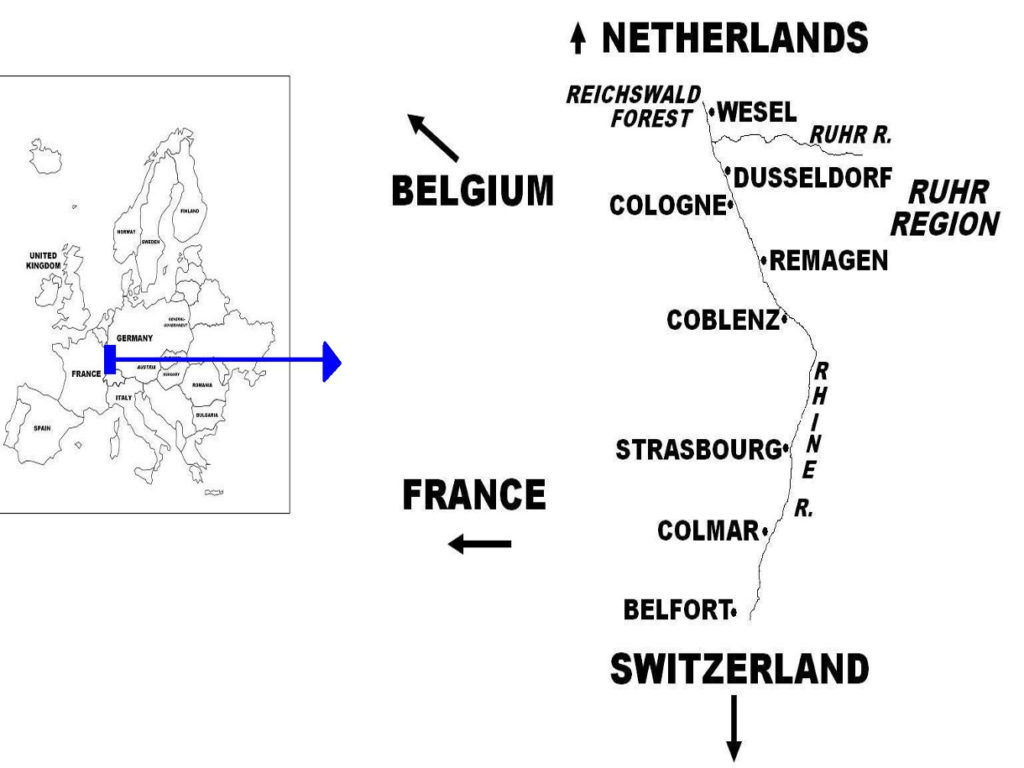

In February 1945, the Western Allies regained the initiative, and attacked on a broad front toward the Rhine River (Figure 42). This new offensive was greatly alarming to Hitler in particular and Germany in general, as the Rhine served as the physical and symbolic gateway to the German heartland. To the north, British 21st Army Group attacked through the Reichswald Forest and reached the Rhine’s west bank, while to the south, U.S. 9th Army, which had been attached to 21st Army Group during the Ardennes battle, advanced for Dusseldorf and Cologne. On February 8, the retreating Germans destroyed the Ruhr dams, flooding the river valley below and stalling the Allied crossing of the Ruhr by two weeks. On February 23, with flood waters receding, U.S. 9th Army crossed the Ruhr, and on March 2, it reached its objective on the Rhine’s west bank.

Further to the south, U.S. 3rd Army reached the Rhine at Coblenz, U.S. 7th Army at Strastbourg, and the French Army at Colmar. By early March 1945, the Allies had broken through to the Rhine’s west bank at many points. Hitler refused the pleas by German field commanders to allow their troops to retreat to the east bank, and ordered that they should hold their ground and fight to the death. Instead, some 400,000 German troops gave up and surrendered. By then, the total number of captured Wehrmacht prisoners in the Western Front had grown to 1.3 million soldiers since the start of the Normandy invasion.

General Eisenhower and the Allied High Command believed that attempting to cross the Rhine on a broad front would lead to heavy losses in personnel, and so they planned to concentrate Allied resources to force a crossing on the north in the British sector. Here also lay the shortest route to Berlin, whose capture was definitely the greatest prize of the war. Beating out the Soviets to Berlin was greatly desired by Prime Minister Churchill and the British High Command, which at this point, the British and American planners believed could be achieved. With Allied focus on the British sector in the north, U.S. 12th and 6th Army Groups to the south were tasked with making secondary attacks in their sectors, tying down German troops there and thus aiding the British offensive.