On October 2, 1937, President Rafael Trujillo met with Dominican residents of Dajabon and promised to act on their complaints against Haitians who were committing “thefts of cattle, provisions, fruits…” President Trujillo also disclosed to the Dajabon assembly that government forces had killed 300 Haitians days earlier.

From October 3-8, 1937, the Dominican Army massacred Haitians in and around the region of Dajabon. The victims were killed in their homes inside plantation camps or were gathered together and brought to secluded locations for execution. The soldiers generally did not fire their rifles at the Haitians, since the bullets could be used to implicate the Dominican Army and even President Trujillo. Instead, the perpetrators used machetes, clubs, and knives, in order to suggest that the killings were carried out by civilians. In some cases, Dominican civilians who helped Haitians escape were also killed. Dominicans also sometimes were misidentified as Haitians and killed.

To identify Haitians, a piece of “perejil” (parsley) was shown to a potential victim who was ordered to name it. As Haitians spoke French Creole and were unable to say “perejil” like the Spanish-speaking Dominicans did, the person was deemed a Haitian and taken away for execution. The Parsley Massacre is so named because of the “perejil” shibboleth.

(Taken from Parsley Massacre – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 3)

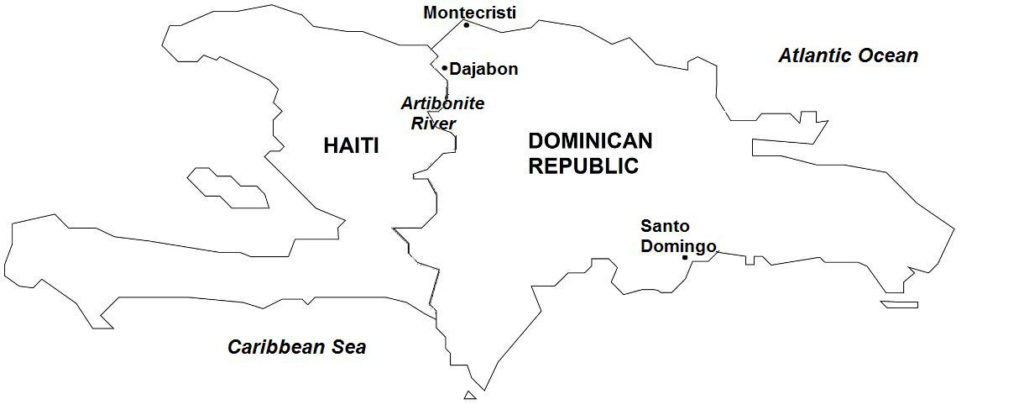

Background In 1930, Rafael Trujillo became President of the Dominican Republic, a country that occupies two-thirds and the eastern section of Hispaniola Island in the Caribbean Sea. President Trujillo actively pursued a racist policy known as “Antihaitianismo” or “Antihaitianism”, directed against Haiti, the Dominican Republic’s western neighbor in Hispaniola.

Antihaitianism emphasized racial differences between the two nationalities, that Dominicans are descendants of former Spanish colonizers and therefore are white (in fact, the vast majority of Dominicans are mulatto descendants of Spanish and black African unions), and that Haitians are black, being descendants of former African slaves. Antihaitianism also espoused the incompatibility of the social, cultural, and linguistic aspects of the two nationalities, that is, since the Dominican Republic was a former colony of Spain, the country therefore exhibits strong Spanish influences. Conversely, Haiti was a former colony of France and therefore manifests strong French influences. Also because of a history of conflict, Antihaitianism also was viewed by Dominicans as the need for vigilance to defend their country against a possible invasion by Haitians who were perceived as wanting to take control of the whole island.

Antihaitianism has its origin in 1805 when Haiti invaded and took control of Santo Domingo (present-day Dominican Republic), then a Spanish colony, and subsequently carried out repressive policies and atrocities, including a number of massacres in the Cibao region. A year earlier, Haiti had gained its independence from France. In 1822, Haiti and Santo Domingo signed a unification agreement, whereby the Haitian government gained authority of western Hispaniola, thereby bringing the whole island under Haiti’s control.

Relations soon deteriorated, however, when the Haitian government attempted to transform Dominican society. The Spanish language was curtailed as were traditional Dominican customs. The Catholic Church was suppressed, church properties were seized, and the foreign clergy was expelled from the island. Land reform was imposed, which ran against traditional Dominican farming practices and which targeted wealthy landowners. When these landowners were forced out of the island, their lands were taken over by Haitian officials.

In 1844, Dominicans rebelled and drove away the Haitians, ending 22 years of occupation. Dominicans then declared independence as the Dominican Republic. In the following years, Haiti carried out many unsuccessful attempts to re-conquer its eastern neighbor. An undefined border between them also added to their acrimonious historical relationship. In 1936, tensions eased somewhat, and President Trujillo and Haitian President Stenio Vincent signed a border treaty that fixed the territorial limits of the two countries.

However, the Dominican Republic’s border regions were frontiers too remote to Santo Domingo and only poorly accessed from other populated areas of the country. Budgetary constraints also restricted the Dominican government’s ability to secure the country’s border. As a result, President Trujillo was infuriated that his political enemies could easily escape to Haiti from where he believed they made plans against him. The porous border also deprived the Dominican Republic of tariff duties from farm produce and other goods that entered from Haiti.

President Trujillo’s greatest concern, however, was the large number of Haitians who entered the Dominican Republic in search of work. Through immigration over the years, Haitian settlements had established and “haitianized” some Dominican border areas. Most of the Haitians were employed as laborers in Dominican sugar plantations. President Trujillo initiated repressive policies aimed at ending the immigration and re-establishing Dominican control of the border areas. In July 1937, the Dominican government expelled 8,000 Haitians. Adding to President Trujillo’s anti-Haitian sentiment was that the Dominican Republic’s economy was being hard hit by the ongoing Great Depression, in which sugar, the country’s main source of revenue, had dropped to 1/20 of its price in the world market.