On October 10, 1945, the Kuomintang (Chinese Nationalist Party) and Communists (Chinese Communist Party) signed the Double Tenth Agreement (officially: “Summary of Conversations Between the Representatives of the Kuomintang and the Communist Party of China”) following 43 days of negotiations. The agreement was an attempt by both sides to prevent a resumption of full-scale fighting in the Chinese Civil War following the surrender of Japan in World War II on September 2, 1945. In the agreement, the communists recognized the Nationalists as the legitimate government, while the Nationalists acknowledged the Communists as the legitimate opposition party. The agreement brought together Nationalist leader Chiang Kai-shek and Communist leader Mao Zedong, the latter accompanied by U.S. Ambassador to China Patrick Hurley, who also accompanied Mao to Chungking, where the negotiations took place.

The agreement was a failure as fighting between the two sides soon resumed.

(Taken from Chinese Civil War – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 1)

When the Japanese forces withdrew from China following their defeat in World War II, the civil war had shifted invariably in favor of the Communists. The Red Army now constituted 1.2 million soldiers and 2 million armed auxiliaries, with many more millions of civilian volunteers ready to provide logistical support. Mao controlled one quarter of China’s territories and one third of the population, all in areas that largely had escaped the destruction of World War II.

By contrast, the Nationalist government had been weakened seriously by World War II. The Nationalists’ territories were devastated and were facing huge economic problems. Thousands of people were left homeless and destitute.

Nearing the end of World War II, the Soviet Union launched a major offensive against the Japanese forces in Manchuria, the industrial heartland where Japan manufactured its weapons and military equipment. The Soviets subsequently withdrew from China but not before allowing the Chinese Communists to occupy large sections of Manchuria (up to 97% of the total area) before the Nationalist Army arrived to take the remaining three Manchurian cities, which were geographically separated from each other.

After the Soviets and the Japanese had withdrawn from China after World War II, armed clashes began to break out between the Nationalist and Communist forces. It seemed only a matter of time before full-scale war would follow. In January 1946, the United States mediated a peace agreement between the two sides. However, the Nationalists and Communists continued their arms build-up and war posturing, which eventually led to the breakdown of the truce in June 1946 and the start of the final and decisive phase of the civil war.

In July 1946, Chiang launched a large-scale offensive with 1.6 million soldiers, with the aim of destroying Mao’s forces in northern China. Because of their superior weapons, the Nationalists advanced steadily. The Red Army also pulled back as part of its strategy of luring on the Nationalists and then letting them overextend their forward lines. In March 1947, the Nationalists captured Yan’an, the former Communists’ headquarters, which really was inconsequential as Mao had moved the bulk of his forces further north.

By September 1948, the Red Army had become much bigger and stronger than the Nationalist forces. Mao finalized plans for a general counter-offensive that ultimately brought the war to an end. From their bases in Manchuria, one million Red Army soldiers swept down over Nationalist-held Shenyang, Changchun, and Jinzhou, encircling these cities and then capturing them. By November 1948, the whole of Manchuria had come under the Communists’ control. Five hundred thousand Nationalist soldiers had been killed, wounded, or captured.

The Red Army continued its offensive to the south and took Beijing and Tianjin following heavy fighting. After incurring losses totaling some 200,000 soldiers, the remaining 260,000 Nationalist defenders in Beijing surrendered to the Communists. By late January 1949, the Communists held all of northern China.

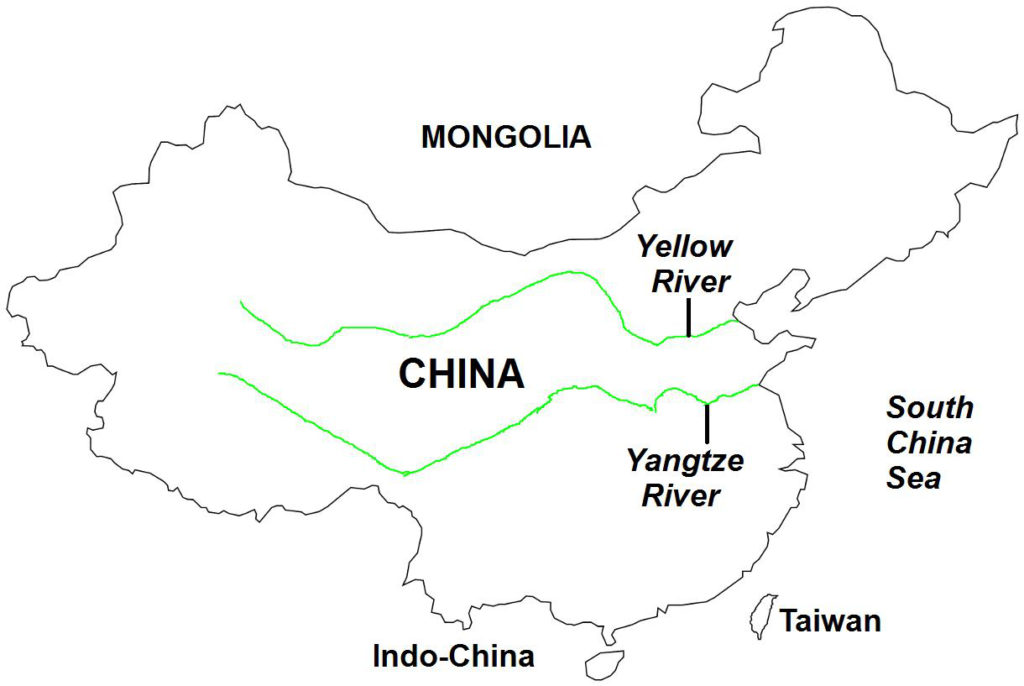

A few weeks before the Beijing campaign, another Red Army offensive consisting of 800,000 soldiers and 600,000 auxiliaries descended on Xuzhou. By mid-January 1949, the Communists had gained control of the Provinces of Shandong, Jiangsu, Anhui, and Henan – and all the territories north of the Yangtze River. More than five million peasants volunteered as laborers for the Red Army, reflecting the Communists’ massive support in the rural areas. Furthermore, many leading Nationalist Army officers had begun to defect to the Communists. The defectors handed the Red Army vital military information, seriously compromising the Nationalists’ war effort.

After the Nationalist Army’s crushing defeats in northern and central China, the war essentially was over. Chiang’s remaining forces were hard pressed to mount further effective resistance against the Red Army’s offensives. Starting with their injudicious offensive in 1946, the Nationalists had lost 1.5 million soldiers, including their best military units. Vast amounts of Nationalist stockpiles of weapons and military hardware had fallen to the Red Army.

With ever-growing numbers of troops and weapons, Communist forces made their final advance south virtually unopposed toward the remaining Nationalist territories in southern and southwestern China. At this time, the United States ended its military support to the Nationalist government. Chiang moved China’s national art treasures and vast quantities of gold and foreign-currency reserves from the National Treasury to the island of Taiwan, causing great uproar among high-ranking officials in his government.

After unsuccessful attempts to negotiate the surrender of the Nationalist government, the Red Army crossed the Yangtze River and captured Nanjing, the former capital of the Nationalists, who meanwhile had moved their headquarters to Guangdong Province.

A disagreement arose among Nationalist leaders whether to defend all remaining territories still under their control or to pull back to a smaller but more defensible area. By October 1949, the Red Army had broken through Guangdong, but not before the Nationalists moved their capital to Chongqing.

On October 1, 1949, Mao declared the establishment of the People’s Republic of China. On December 10, 1949, as Red Army forces were encircling Chengdu, the last Nationalist stronghold, Chiang departed on a plane for Taiwan. Joining him in Taiwan were about two million Chinese mainlanders, mostly Kuomintang officials, Nationalist Army officers and soldiers, prominent members of society, the academe, and the religious orders. On March 1, 1950, Chiang resumed his position as China’s president and declared Taiwan as the temporary capital of the Republic of China.

In the months that followed, fighting continued to flare up between the military forces of the two Chinese governments, mainly for possession of the islands along the waters separating their countries. Since no truce or peace agreement was made by and between the two governments that do not recognize the legitimacy of the other, to this day, the two countries are technically still at war.