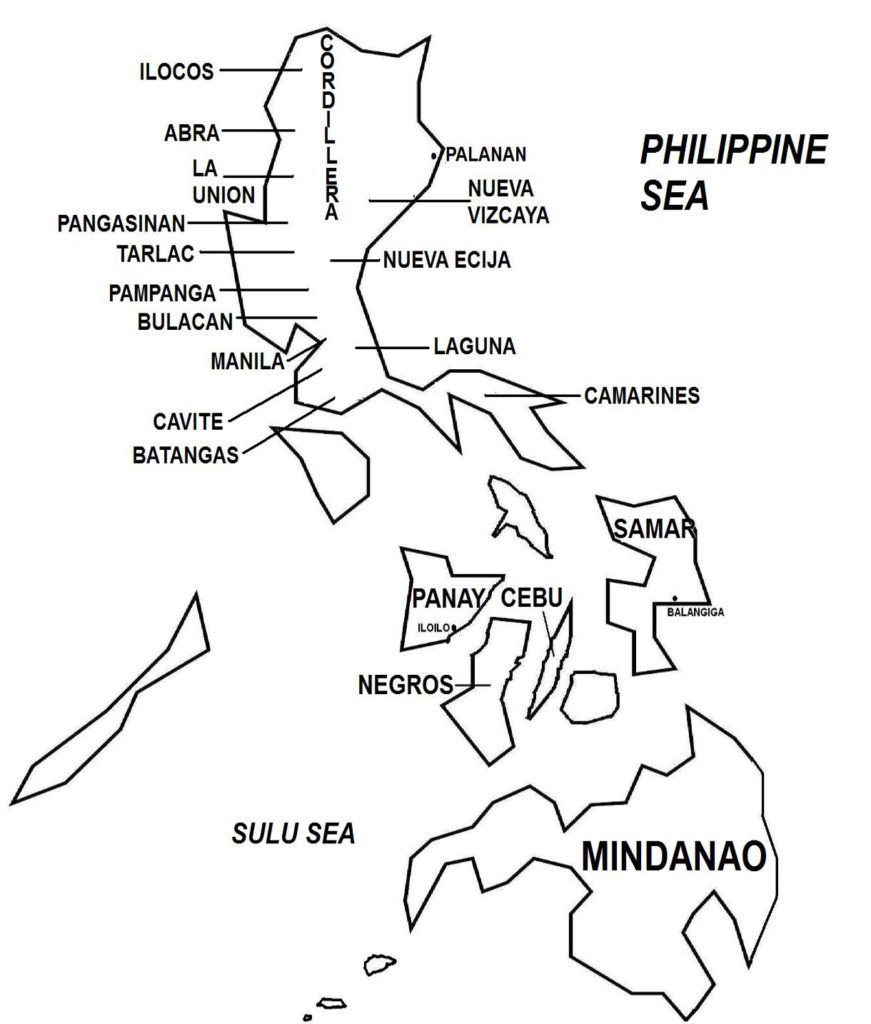

On March 23, 1901, U.S. Army-recruited Filipino soldiers and their American officers captured Aguinaldo in Palanan, Isabela; the Filipino leader soon pledged allegiance to the United States and called on other revolutionaries to end hostilities and surrender. However, the war continued, since Aguinaldo had previously set up a line of succession to the revolutionary leadership, a post that was filled after his capture by General Miguel Malvar, who operated mainly in Batangas, and also in nearby provinces.

The year 1901 saw the most intense phase of the U.S. reconcentrado policy implemented in many areas held by the revolutionaries. In January of that year, interior villages in Marinduque were depopulated and their residents moved to coastal guarded camps before the U.S. Army launched inland operations to flush out the insurgents. Three months later, in April, U.S. forces carried out similar operations in Abra in northern Luzon. Also in April, U.S. forces launched a scorched-earth sixty-mile wide destruction of villages and farmlands in Panay Island from Iloilo in the south to Capiz in the north. Then in September, in the event known as the Balangiga Massacre, Filipino guerillas attacked an American garrison in Balangiga, Samar, killing nearly all the U.S. soldiers. In reprisal, U.S. General Jacob Smith issued the following instructions to U.S. Marines who were tasked with pacifying Samar, “I want no prisoners. I wish you to kill and burn, the more you kill and the more you burn, the more you will please me…The interior of Samar must be made into a howling wilderness”. The age limit specified was ten, i.e. all persons above this age was to be killed.

(Taken from Philippine-American War – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 4)

Background Throughout the Spanish colonial rule (which began in 1565) over much of the archipelago that now comprises the country called the Philippines, the native inhabitants of the islands often offered resistance and launched scores of mostly local or limited-scope rebellions, all of which generally failed to have a marked or long-lasting effect on Spain’s political and military control of the colony. Developments in the 19th century, however, sparked the emergence of a unified collective Filipino consciousness among the separate islands’ numerous and diverse ethnic groups, which soon led to the development of a nationalist vision for the archipelago. Among these developments were the opening in 1834 of Manila (as well as other ports in the Philippine islands) to world trade, the entry of foreign firms (e.g. British, American, French, Swiss, and German) to compete with the erstwhile Spanish-owned commercial and trade monopolies, the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869 that accelerated European-Asian trade, and the 1868 Glorious Revolution in Spain that established a progressive government which in turn appointed a liberal, democratic-minded Governor-General in the Philippines.

Traditional Philippine colonial society, which was stratified into the peninsulares (Spanish nationals born in Spanish) and insulares (Spanish nationals born in the Philippines) upper ruling classes, the mestizo (descendants of Spanish-native unions) and pre-colonial native nobility lower ruling classes, and the masses of indios (natives) lower classes (comprising peasants, and rural and urban laborers), was transformed during the second half of the 19th century with the rise of the middle class, which consisted of landed farmers, teachers, lawyers, physicians, and government workers. The members of this new social class, which emerged and benefited from the central government’s political and economic reforms, placed great emphasis on education and sent their children for advanced schooling in Manila and even in Spain and other European cities, thereby producing a second generation of the enlightened (i.e. educated) middle class, which was called the ilustrado class.

This ilustrado middle class, working together with political exiles from the islands, organized as the Propaganda Movement during the last decades of the 19th century and established its main base of activities in Spain, where progressive ideas were prevalent and generally tolerated, and not in their homeland, which although officially run by a civilian government under the Governor-General, was highly influenced by the powerful Catholic religious orders (Augustinians, Dominicans, and Franciscans), which held the real political power especially in the countryside where most of the natives resided. The Propaganda Movement pursued its ideological views through the fine arts (painting, sculpture, etc.) and print (most notably the newspaper La Solidaridad and Jose Rizal’s two scathing novels against the Spanish colonial system in the Philippines). Politically, the movement did not seek independence and instead called on Spain to implement reforms including local representation in the Spanish parliament, civil and social reforms, and the end of the religious orders’ political and social domination of the colony. However, Spain was intransigent to change and by 1896, the Propaganda Movement had sputtered and effectively ceased to exist.

In 1892, a reformist organization, La Liga Filipina (The Philippine League), was founded in Manila (by Rizal who had returned to the Philippines) which, in its brief existence that was cut short by Spanish authorities and Rizal’s arrest and deportation, was crucial to advancing the nationalist cause because it had members from the lower social classes who became exposed to liberal, progressive ideas. Then on La Liga Filipina’s dissolution, Andres Bonifacio, a Manila warehouse worker, and his other associates from the lower classes, secretly organized the Katipunan (Filipino: Samahang Kataastaasan, Kagalanggalang Katipunan ng mga Anak ng Bayan; English: Supreme and Most Honorable Society of the Children of the Nation), a militant mass-based radical movement that advocated the establishment of an independent Philippine state through violent revolution against Spain.

By 1896, the rebel movement numbered some 30,000 members, drawn mostly from the rural and urban lower class but also from nationalist-minded middle class leaders, professionals, and even local public officials, with the latter group heading many of the insurgent organization’s local and regional revolutionary councils. The movement spread throughout much of the archipelago with active recruitment campaigns being carried out particularly in Manila’s nearby provinces including Manila (province), Bulacan, Pampanga, Nueva Ecija, Tarlac, Cavite, Laguna, and Batangas, and also other parts of Luzon as well as the Visayan islands, and some Christian parts of Mindanao.

Spanish authorities soon learned of the clandestine organization and conducted widespread arrests of suspected members, which forced the as yet unprepared insurgents to commence hostilities with an attack on Manila in late August 1896 in an attempt to overthrow the Spanish government. The Spanish Army repulsed the attack and Bonifacio and his insurgent forces fell back to the hills east of Manila where they reorganized as a guerilla militia that engaged in hit-and-run warfare. Provincial rebel commands also initiated similar armed uprisings, which likewise were easily quelled by local Spanish Army units, except in Cavite where the revolutionary leaders, most notably Emilio Aguinaldo (who later would play a major role in the Philippine-American War), defeated and expelled the Spanish forces and gained control of much of the province. Tensions soon developed between Bonifacio and Aguinaldo, which led to a power struggle. By March 1897, Aguinaldo had emerged as the organization’s de facto leader, having executed his rival, although many provincial revolutionary commands operated as virtually independent commands and others, particularly in the Visayan islands, were distrustful of being ethnically dominated by revolutionaries from Luzon in the post-war period.

By May 1897, with the arrival of reinforcements and weapons from Spain, the Spanish Army launched a major offensive that gained back control of Cavite and many other insurgent-occupied areas, and Aguinaldo was forced to be constantly on the move until finding relatively safe refuge in the mountains north of Manila where he carried out a guerilla struggle. By this time, the Spanish authorities realized the difficulty of capturing Aguinaldo and sought the mediation of influential Filipinos and mestizos (some of whom had been involved with the rebel movement but had since been won over to Spain with the offer of amnesty). After several months, in December 1897, these mediation efforts led to the signing by Filipino and Spanish representatives of the Pact of Biak-na-Bato, a peace treaty that ended hostilities.

The peace treaty stipulated that in exchange for Aguinaldo and other revolutionary leaders ending the rebellion, surrendering a pre-determined number of firearms, and going into voluntary exile abroad, Spain would pay Aguinaldo and the revolutionary leadership a monetary indemnity (to be paid in three installments). The two sides did not fully comply with the treaty’s provisions, and much tension and mistrust persisted. On December 23, 1897, Aguinaldo and his party of revolutionaries did go to voluntary exile in Hong Kong where they plotted to renew hostilities with a cache of newly acquired weapons that were purchased using the indemnity money given by the Spanish government. In the islands, the Spanish Army continued to face sporadic local armed resistance and thus failed to fully pacify the archipelago, and consequently also could not implement amnesty.

At this stage of political uncertainty, the Spanish-American War broke out on April 25, 1898, with hostilities centered mainly in Cuba, with the United States taking the side of the Cuban revolutionaries who had been engaged in a protracted independence war against colonial Spain for three years (since February 1895). The United States then sent a naval squadron to the Philippines, and on May 1, 1898 at the Battle of Manila Bay, the U.S. ships, commanded by Commodore George Dewey, dealt a crushing defeat on the Spanish Navy. Commodore Dewey then imposed a naval blockade of Manila Bay while awaiting the formation in the United States of ground troops to carry out the land war against the Spanish Army in Manila and the Philippines.

Meanwhile, U.S. consular officials in Singapore met with Aguinaldo, these talks soon becoming a subject of great controversy, as the Filipino leader later asserted that these officials, ostensibly representing the U.S. government, promised him that in exchange for the Filipino revolutionaries’ support to the United States in the war against Spain, the U.S. government would recognize Philippine independence. However, the U.S. government declared that no such promise to Aguinaldo was made and that the U.S. consular officials were not in authority to enter into negotiations for and in behalf of the United States.

At any rate, the meetings brought about a tacit alliance between the Filipino revolutionaries and the United States, and a U.S. ship transported Aguinaldo and his party from Hong Kong to the Philippines, with the revolutionary leaders arriving in Manila on May 19, 1898 to restart the uprising against Spain. Aguinaldo’s return had a catalyzing effect, as the revolution, although not completely dying down during his absence, rose to such an intensity that within a short period, insurgent provincial commands had seized control of much of the territories, including the provinces of Laguna, Batangas, Bulacan, Nueva Ecija, Bataan, Tayabas, and Camarines. By July 1898, the Filipino insurgents controlled much of the archipelago, except Manila, which was surrounded and placed under siege by some 12,000 revolutionary troops. Sensing imminent victory, on June 12, 1898, Aguinaldo declared the independence of the Philippines, which was followed six days later by the formation of a dictatorial government, with himself as the new country’s president. On June 23, he abolished the dictatorial government, instead creating a revolutionary government, also with himself as president.

Meanwhile, on June 30, 1898, the first of three batches of U.S. ground troops arrived and were landed in Cavite, south of Manila; by late July 1898, General Wesley Merritt, commander-in-chief of the Philippine Expeditionary Forces, had arrived and the total U.S. Army troop strength numbered 12,000 soldiers. Then as U.S. forces deployed closer to Manila, skirmishes began to break out, the most serious taking place on August 8, 1898 when eight American soldiers were killed or wounded. These incidents prompted the U.S. military command to suspect that the Filipino revolutionaries were passing on information to Spanish authorities about the American troop movement, highlighting the increasingly deteriorating relations between the two nominal allies.

Meanwhile, the anticipated showdown between U.S. and Spanish forces in the Philippines did not materialize, as the Spanish central government in Madrid realized imminent defeat in Cuba, the Philippines, and Puerto Rico. On August 12, 1898 in Washington, D.C., the United States and Spain signed the “Protocol of Peace” that ended hostilities between the two countries; this agreement did not reach the Philippines until August 16. However, U.S. and Spanish authorities in Manila also entered into secret negotiations, which led to the two sides agreeing to carry out a mock battle for control of Manila; the plan was aimed at preserving Spanish military honor that otherwise would be tarnished if the Spanish Army surrendered without a fight, and the two sides would be spared unnecessary loss of lives. More importantly for the two powers and in the context of regional and global rivalries (with the other European powers operating in the Asia-Pacific), Manila (and thus the Philippines) would be passed on from Spain to the United States, and without the participation of the Filipino revolutionaries. Without disclosing the plan, U.S. authorities warned Aguinaldo to keep his forces inside Filipino defensive lines, and faced the risk of meeting U.S. fire if they advanced.

As agreed, on August 13, 1898, Spanish and American forces carried out the mock battle, which involved an assault by U.S. forces, some cursory exchange of gunfire, and a pre-determined signal to indicate that the Spanish Army was ready to surrender and turn over Manila to the Americans. The battle ended successfully, with U.S. forces gaining control of the capital, although it was marred somewhat when, at the start of the American offensive, Filipino troops also advanced from their lines, prompting an exchange of gunfire between the two sides that claimed six American and forty-nine Spanish troop casualties.

In the aftermath, Filipino forces gained control of sections of Manila and Aguinaldo insisted in joint Filipino-American occupation of the capital. On August 17, 1898, U.S. President William McKinley informed General Elwell Otis that only U.S. forces were to occupy Manila, thus indicating the United States’ intention to keep the Philippines. A few days earlier, August 14, the United States established a military government in the islands, with General Merritt taking the position of (the first) military Governor. U.S. authorities threatened the use of armed force against Aguinaldo if the Filipino units were not withdrawn from the capital; on September 15, 1898, the latter reluctantly withdrew his forces to a defensive line extending across the perimeter of the capital.

In late September 1898, American and Spanish representatives met in Paris to begin work on a treaty to officially end the war, particularly with regards to the future of Spanish territories involved in the conflict. Negotiations were difficult with respect to the Philippines, as the United States demanded possession of first only Luzon and later the whole archipelago, which Spain strongly opposed. Finally, however, on December 10, 1898, the two countries signed the Treaty of Paris, where Spain ceded Cuba, Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Philippines to the United States; with regards to the Philippines particularly, the U.S. government paid Spain the amount of U.S. $20 million for “Spanish improvements” made in the colony.

The treaty, which needed to be approved by the two countries, experienced considerable opposition in the U.S. and Spanish legislatures. On March 19, 1899, Spain ratified the treaty with the intervention of the Spanish monarchy. In the U.S. Senate, a vote on the treaty set for February 6, 1899 appeared to just fall short of the two-thirds majority needed for approval. However, developments in the Philippines would influence the vote.

In early January 1899, U.S. ships trying to land American troops in Iloilo City were blocked by thousands of local Filipino troops. From Malolos (where the Filipino central government was headquartered), Aguinaldo threatened to use force if the Americans forced a landing. In the midst of rising tensions, on January 4, 1899, President McKinley’s “Benevolent Assimilation” policy of American annexation of the islands was released, generating even more discord.