In December 1950, French and allied forces came under the command of General Jean de Lattre de Tassigny, a highly respected veteran officer of World War II, whose arrival greatly raised troop morale. To defend Hanoi, Haiphong, and the Red River Delta, he constructed an extensive network of fortifications (called the De Lattre Line, Figure 3) that covered 3,200 kilometers from the northern coast to the Chinese border and consisted of about 1,200 concrete fortifications, each armed with and supported by artillery, armored, and air units.

In 1951, the Viet Minh, believing that the French military was verging on defeat, launched several offensives on the De Lattre Line. The first attack occurred in January 1951 at Vinh Yen, where 20,000 Viet Minh troops advanced using human-wave assaults. After initially gaining ground, the attack was repulsed after four days of fighting by heavy French artillery bombardments and air strikes. Then in March 1951, Viet Minh forces attacked lightly defended Mao Khe town in preparation to advancing toward Haiphong. The Viet Minh succeeded in entering the town, where it engaged the small French garrison there in some intense street fighting. But the French soon counter-attacked, and repulsed the Viet Minh after four days of fighting. In May-June 1951, in fighting at Ninh Binh, Nam Dinh, Phu Ly, and Phat Diem, collectively known as the Battle of the Day River, French superior firepower beat back the numerically superior Viet Minh, the latter suffering 9,000 soldiers killed or wounded, and 1,000 captured.

The De Lattre Line, however, was not secure in all places, as Viet Minh infiltration teams entered through gaps between fortifications. Some 30,000 Viet Minh cadres, including communist agitators, soon established Viet Minh influence in 5,000 of the 7,000 villages in the Red River Delta area. In November 1951, General de Lattre went on the offensive, air-dropping commandos in Hoa Binh town, deep inside Viet Minh territory. The town was taken, but large numbers of Viet Minh forces laid siege to the French commandos, cutting off the approaches to Hoa Binh through the Black River and along Route Coloniale 6. In late February 1952, French forces were forced to evacuate the town.

(Taken from First Indochina War – Wars of the 20th Century – Twenty Wars in Asia)

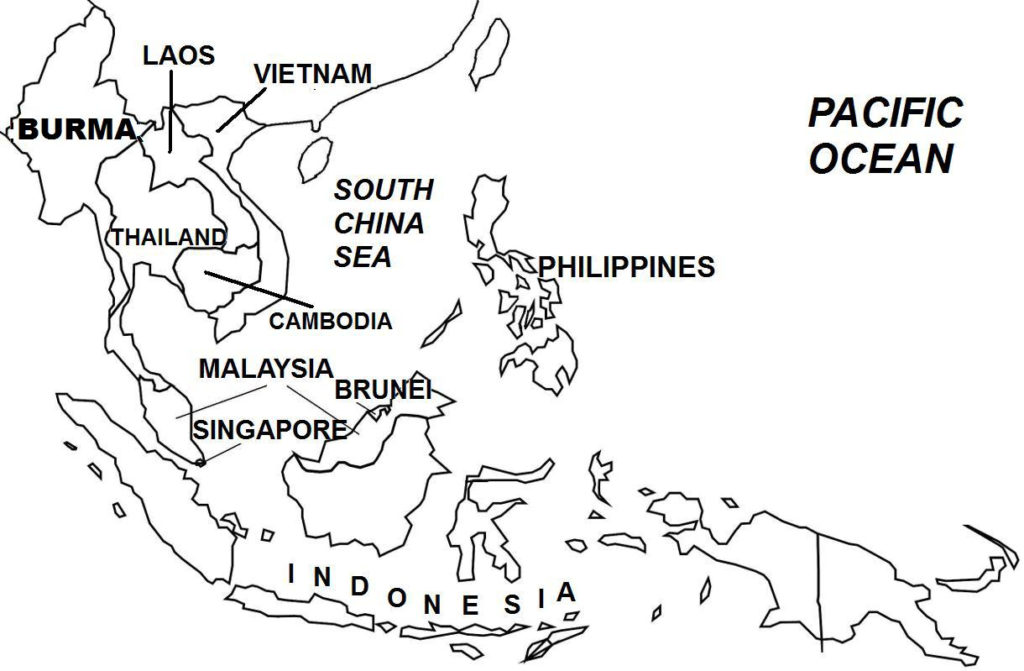

Aftermath By the time of the Battle of Dien Bien Phu, France knew that it could not win the war, and turned its attention on trying to work toward a political settlement and an honorable withdrawal from Indochina. By February 1954, opinion polls at home showed that only 8% of the French population supported the war. However, the Dien Bien Phu debacle dashed French hopes of negotiating under favorable withdrawal terms. On May 8, 1954, one day after the French defeat at Dien Bien Phu, representatives from the major powers: United States, Soviet Union, Britain, China, and France, and the Indochina states: Cambodia, Laos, and the two rival Vietnamese states, Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRV) and State of Vietnam, met at Geneva (the Geneva Conference) to negotiate a peace settlement for Indochina. The Conference also was envisioned to resolve the crisis in the Korean Peninsula in the aftermath of the Korean War (separate article), where deliberations ended on June 15, 1954 without any settlements made.

On the Indochina issue, on July 21, 1954, a ceasefire and a “final declaration” were agreed to by the parties. The ceasefire was agreed to by France and the DRV, which divided Vietnam into two zones at the 17th parallel, with the northern zone to be governed by the DRV and the southern zone to be governed by the State of Vietnam. The 17th parallel was intended to serve merely as a provisional military demarcation line, and not as a political or territorial boundary. The French and their allies in the northern zone departed and moved to the southern zone, while the Viet Minh in the southern zone departed and moved to the northern zone (although some southern Viet Minh remained in the south on instructions from the DRV). The 17th parallel was also a demilitarized zone (DMZ) of 6 miles, 3 miles on each side of the line.

The ceasefire agreement provided for a period of 300 days where Vietnamese civilians were free to move across the 17th parallel on either side of the line. About one million northerners, predominantly Catholics but also including members of the upper classes consisting of landowners, businessmen, academics, and anti-communist politicians, and the middle and lower classes, moved to the southern zone, this mass exodus was prompted by the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) and State of Vietnam in a massive propaganda campaign, as well as the peoples’ fears of repression under a communist regime.

In August 1954, planes of the French Air Force and hundreds of ships of the French Navy and U.S. Navy (the latter under Operation Passage to Freedom) carried out the movement of Vietnamese civilians from north to south. Some 100,000 southerners, mostly Viet Minh cadres and their families and supporters, moved to the northern zone. A peacekeeping force, called the International Control Commission and comprising contingents from India, Canada, and Poland, was tasked with enforcing the ceasefire agreement. Separate ceasefire agreements also were signed for Laos and Cambodia.

Another agreement, titled the “Final Declaration of the Geneva Conference on the Problem of Restoring Peace in Indo-China, July 21, 1954”, called for Vietnamese general elections to be held in July 1956, and the reunification of Vietnam. France DRV, the Soviet Union, China, and Britain signed this Declaration. Both the State of Vietnam and the United States did not sign, the former outright rejecting the Declaration, and the latter taking a hands-off stance, but promising not to oppose or jeopardize the Declaration.

By the time of the Geneva Conference, the Viet Minh controlled a majority of Vietnam’s territory and appeared ready to deal a final defeat on the demoralized French forces. The Viet Minh’s agreeing to apparently less favorable terms (relative to its commanding battlefield position) was brought about by the following factors: First, despite Dien Bien Phu, French forces in Indochina were far from being defeated, and still held an overwhelming numerical and firepower advantage over the Viet Minh; Second, the Soviet Union and China cautioned the Viet Minh that a continuation of the war might prompt an escalation of American military involvement in support of the French; and Third, French Prime Minister Pierre Mendes-France had vowed to achieve a ceasefire within thirty days or resign. The Soviet Union and China, fearing the collapse of the Mendes-France regime and its replacement by a right-wing government that would continue the war, pressed Ho to tone down Viet Minh insistence of a unified Vietnam under the DRV, and agree to a compromise.

The planned July 1956 reunification election failed to materialize because the parties could not agree on how it was to be implemented. The Viet Minh proposed forming “local commissions” to administer the elections, while the United States, seconded by the State of Vietnam, wanted the elections to be held under United Nations (UN) oversight. The U.S. government’s greatest fear was a communist victory at the polls; U.S. President Eisenhower believed that “possibly 80%” of all Vietnamese would vote for Ho if elections were held. The State of Vietnam also opposed holding the reunification elections, stating that as it had not signed the Geneva Accords, it was not bound to participate in the reunification elections; it also declared that under the repressive conditions in the north under communist DRV, free elections could not be held there. As a result, reunification elections were not held, and Vietnam remained divided.

In the aftermath, both the DRV in the north (later commonly known as North Vietnam) and the State of Vietnam in the south (later as the Republic of Vietnam, more commonly known as South Vietnam) became de facto separate countries, both Cold War client states, with North Vietnam backed by the Soviet Union, China, and other communist states, and South Vietnam supported by the United States and other Western democracies.

In April 1956, France pulled out its last troops from Vietnam; some two years earlier (June 1954), it had granted full independence to the State of Vietnam. The year 1955 saw the political consolidation and firming of Cold War alliances for both North Vietnam and South Vietnam. In the north, Ho Chi Minh’s regime launched repressive land reform and rent reduction programs, where many tens of thousands of landowners and property managers were executed, or imprisoned in labor camps. With the Soviet Union and China sending more weapons and advisors, North Vietnam firmly fell within the communist sphere of influence.

In South Vietnam, Ngo Dinh Diem, whom Bao Dai appointed as Prime Minister in June 1954, also eliminated all political dissent starting in 1955, particularly the organized crime syndicate Binh Xuyen in Saigon, and the religious sects Hoa Hao and Cao Dai in the Mekong Delta, all of which maintained powerful armed groups. In April-May 1955, sections of central Saigon were destroyed in street battles between government forces and the Binh Xuyen militia.

Then in October 1955, in a referendum held to determine the State of Vietnam’s political future, voters overwhelmingly supported establishing a republic as campaigned by Diem, and rejected the restoration of the monarchy as desired by Bao Dai. Widespread irregularities marred the referendum, with an implausible 98% of voters favoring Diem’s proposal. On October 23, 1955, Diem proclaimed the Republic of Vietnam (later commonly known as South Vietnam), with himself as its first president. Its predecessor, the State of Vietnam was dissolved, and Bao Dao fell from power.

In early 1956, Diem launched military offensives on the Viet Minh and its supporters in the South Vietnamese countryside, leading to thousands being executed or imprisoned. Early on, militarily weak South Vietnam was promised armed and financial support by the United States, which hoped to prop up the regime of Prime Minister (later President) Diem, a devout Catholic and staunch anti-communist, as a bulwark against communism in Southeast Asia.

In January 1955, the first shipments of American weapons arrived, followed shortly by U.S. military advisors, who were tasked to provide training to the South Vietnamese Army. The U.S. government also endeavored to shore up the public image of the somewhat unknown Diem as a viable alternative to the immensely popular Ho Chi Minh. However, the Diem regime was tainted by corruption and nepotism, and Diem himself ruled with autocratic powers, and implemented policies that favored the wealthy landowning class and Catholics at the expense of the lower peasant classes and Buddhists (the latter comprised 70% of the population).

By 1957, because of southern discontent with Diem’s policies, a communist-influenced civilian uprising had grown in South Vietnam, with many acts of terrorism, including bombings and assassinations, taking place. Then in 1959, North Vietnam, frustrated at the failure of the reunification elections from taking place, and in response to the growing insurgency in the south, announced that it was resuming the armed struggle (now against South Vietnam and the United States) in order to liberate the south and reunify Vietnam. The stage was set for the cataclysmic Second Indochina War, more popularly known as the Vietnam War. (Excerpts taken from Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 5: Twenty Wars in Asia.)