Ethiopian-Cuban forces advanced toward the strategic Kara Marda Pass, where the Somalis had built a defensive line. Bypassing the Pass through the north and then turning east, one Ethiopian-Cuban unit joined with another force approaching from the west to launch a pincers attack on the Somali defenders. By early March 1978, the Ethiopian-Cuban forces had captured the Kara Marda Pass and were moving rapidly east toward the Ogaden plains. As fears of an Ethiopian invasion of Somalia increased, on February 9, 1978, Somali President Barre issued a general mobilization and placed the country in a state of emergency. In early March 1978, Ethiopian-Cuban forces attacked Jijiga, where remnants of the Somali Army-WSLF forces had organized a last major defense of the Ogaden. But their lines quickly fell apart under the weight of the armored, artillery, and air attacks. The Battle of Jijiga was a crushing defeat for the Somali Army, with some 3,000 soldiers killed. On March 9, 1978, the Somali government ordered a general retreat from the Ogaden; by this time, however, the Somali Army, now abandoning their weapons and equipment in the field, and together with the WSLF fighters, and tens of thousands of civilians, were making a hasty, chaotic retreat toward the Somali border. Further Ethiopian-Cuban advances across the Ogaden recaptured other areas: Degehabur (March 6), Filtu (March 8), Delo (March 12), and Kelafo (March 13).

The Ethiopian government now faced the enticing prospect of advancing right into Somalia. Ultimately, the Soviet Union prevailed upon the Ethiopian Derg regime to stop at the border; on March 23, 1978, with much of the fighting dying down, Ethiopia declared victory and the war over. Estimates of combat casualties are: over 6,000 killed and 10,000 wounded in the Ethiopian Army, and over 6,000 killed and 2,000 wounded in the Somali Army. Some 400 Cubans and 30 Soviets also lost their lives. A combined 50 planes and over 300 tanks and armored vehicles also were destroyed. Furthermore, some 750,000 Ogaden inhabitants (mainly ethnic Somali and Oromo) fled from their homes and ended up as refugees in Somalia.

(Excerpts taken from Ogaden War – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 4)

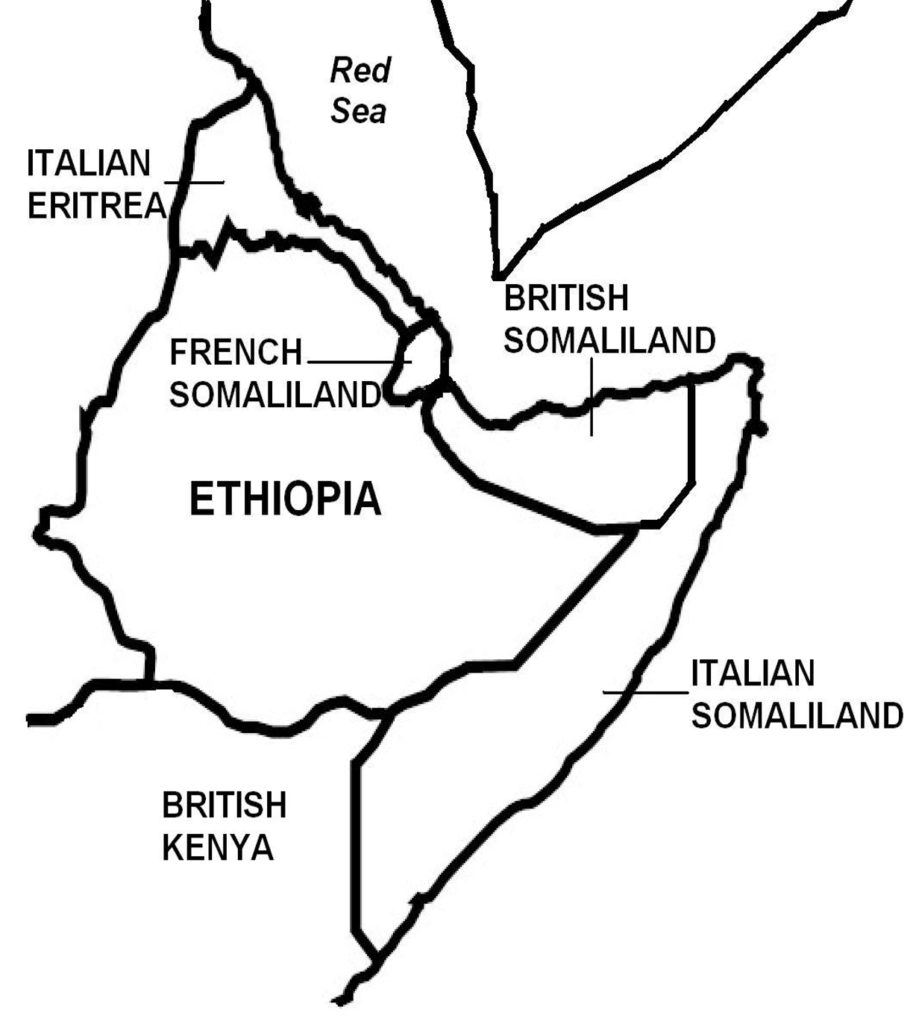

Background In December 1950, with Allied approval, the United Nations granted Italy a trusteeship over Italian Somaliland on the condition that Italy grants the territory its independence within ten years. On June 26, 1960, Britain granted independence to British Somaliland, which became the State of Somaliland, and a few days later, Italy also granted independence to the Trust Territory of Somaliland (the former Italian Somaliland). On July 1, 1960, the two new states merged to form the Somali Republic (Somalia).

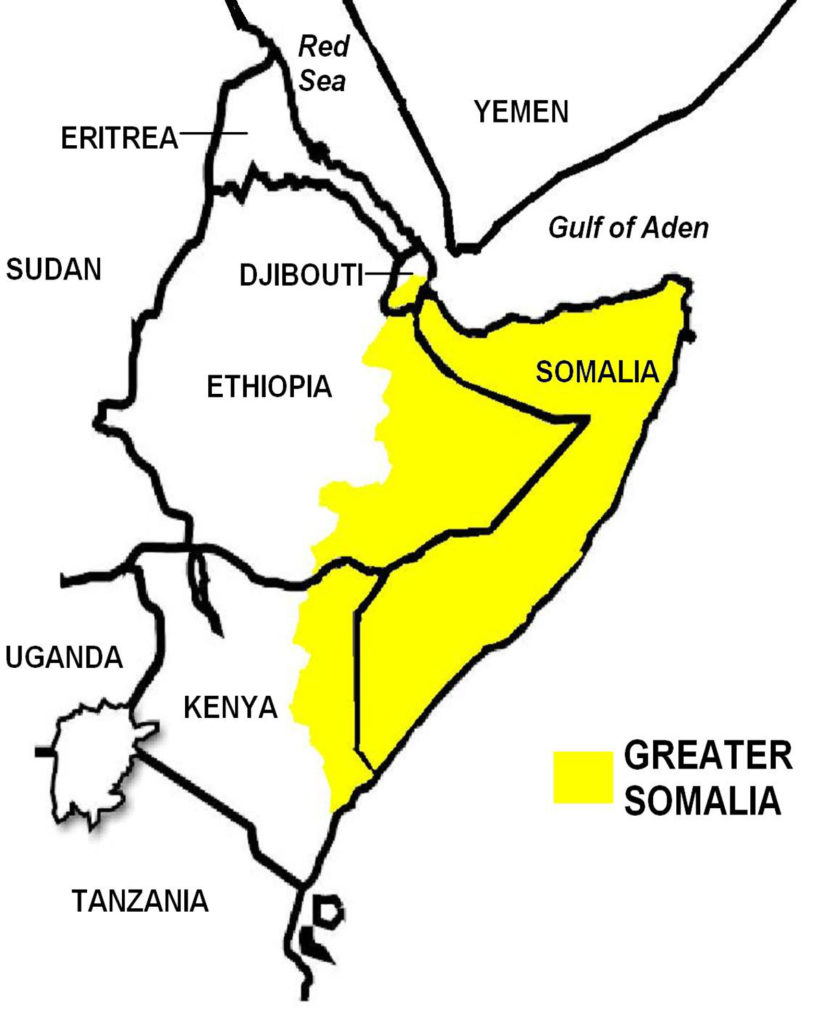

The newly sovereign enlarged state had as its primary foreign affairs mission the fulfillment of “Greater Somalia” (also known as Pan-Somalism; Figure 29), an irredentist concept that sought to bring into a united Somali state all ethnic Somalis in the Horn of Africa who currently were residing in neighboring foreign jurisdictions, i.e. the Ogaden region in Ethiopia, Northern Frontier District (NFD) in Kenya, and French Somaliland. Somalia officially did not claim ownership to these foreign territories but desired that ethnic Somalis in these regions, particularly where they formed a population majority, be granted the right to decide their political future, i.e. to remain with these countries or to secede and merge with Somalia.

Nationalist Somalis in Kenya and Ethiopia, desiring to be joined with Somalia, soon launched guerilla insurgencies. In the Ogaden region, many guerilla groups organized, the foremost of which was the Western Somali Liberation Front (WSLF), founded in 1960, just after Somalia gained its independence. The Somali government began to build its armed forces, eventually setting as a goal a force of about 20,000 troops that it deemed was powerful enough to realize the dream of Greater Somalia. But constrained by economic limitations, Somalia sought the assistance of various Western powers, particularly the United States, but the latter only promised to provide military resources for a 5,000-strong armed forces, which it deemed was sufficient for Somalia to defend its borders against external threats.

The Somali government then turned to communist states, particularly the Soviet Union; although these countries’ Marxist ideology ran contrary to its own democratic institution, Somalia viewed this as a means to be political self-reliant and not be too dependent on the West, and to court both sides in the Cold War. Thus, for nearly two decades after gaining its independence, Somalia received military support from both western and communist countries.

In 1962, the Soviet Union provided Somalia with a substantial loan under generous terms of repayment, allowing the Somali government to build in earnest an offense-oriented armed forces; subsequent Soviet loans and military assistance led to the perception in the international community that Somalia fell under the Soviet sphere of influence, bolstered further as Soviet planes, tanks, artillery pieces, and other military hardware were supplied in large quantities to the Somali Army Forces.

Tensions between Ethiopian security forces and the Ogaden Somalis sporadically led to violence that soon deteriorated further with Somali Army units intervening, leading to border skirmishes between Ethiopian and Somali regular security units. Large-scale fighting by both sides finally broke out in February 1964, which was triggered by a Somali revolt in June 1963 at Hodayo. Somali ground and air units came in support of the rebels but Ethiopian planes gained control of the skies and attacked frontier areas, including Feerfeer and Galcaio. Under mediation efforts provided by Sudan representing the Organization of African Unity (OAU), in April 1964, a ceasefire was agreed that imposed a separation of forces and a demilitarized zone on the border. In the aftermath, in late 1964, Ethiopia entered into a mutual defense treaty with Kenya (which also was facing a rebellion by local ethnic Somalis supported by the Somali government) in case of a Somali invasion; this treaty subsequently was renewed in 1980 and then in 1987.

On October 21, 1969, a military coup overthrew Somalia’s democratically elected civilian government and in its place, a military junta called the Supreme Revolutionary Council (SRC) was set up and led by General Mohamed Siad Barre, who succeeded as president of the country. The SRC suspended the constitution, banned political parties, and dissolved parliament, and ruled as a dictatorship. The country was renamed the Somali Democratic Republic. Exactly one year after the coup, on October 21, 1970, President Barre declared the country a Marxist state, although a form of syncretized ideology called “scientific revolution” was implemented, which combined elements of Marxism-Leninism, Islam, and Somali nationalism. The SRC forged even closer diplomatic and military ties with the Soviet Union, which led in July 1974 to the signing of the Treaty of Friendship and Cooperation, where the Soviets increased military support to the Somali Army. Earlier in 1972, under a Somali-Soviet agreement, the Russians developed the Somali port of Berbera, converting it into a large naval, air, and radar and communications facility that allowed the Soviets to project power into the Middle East, Red Sea, and Persian Gulf. The Soviets also established many new military airfields, including those in Mogadishu, Hargeisa, Baidoa, and Kismayo.

Under pressure from the Soviet government to form a “vanguard party” along Marxist lines, in July 1976, President Barre dissolved the SRC which he replaced with the Somali Revolutionary Socialist Party (SRSP), whose Supreme Council (politburo) formed the new government, with Barre as its Secretary General. The SRSP, as the sole legal party, was intended to be a civilian-run entity to replace the military-dominated SRC; however, since much of the SRC’s political hierarchy simply moved to the SRSP, in practice, not much changed in governance and Barre continued to rule as de facto dictator.

With a greatly enhanced Somali military capability, President Barre pressed irredentist aspirations for Greater Somalia, stepping up political rhetoric against Ethiopia and spurning third-party mediations to resolve the emerging crisis. Then in the mid-1970s, favorable circumstances allowed Somalia to implement its irredentist ambitions. During the first half of 1974, widespread military and civilian unrest gripped Ethiopia, rendering the government powerless. In September 1974, a group of junior military officers called the “Coordinating Committee of the Armed Forces, Police, and Territorial Army”, which simply was known as “Derg” (an Ethiopian word meaning “Committee” or “Council”), seized power after overthrowing Ethiopia’s long-ruling aging monarch, Emperor Haile Selassie. The Derg succeeded in power, dissolved the Ethiopian parliament and abolished the constitution, nationalized rural and urban lands and most industries, ruled with absolute powers, and began Ethiopia’s gradual transition from an absolute monarchy to a Marxist-Leninist one-party state.

Ethiopia traditionally was aligned with the West, with most of its military supplies sourced from the United States. But with its transition toward socialism, the Derg regime forged closer ties with the Soviet Union, which led to the signing in December 1976 of a military assistance agreement. Simultaneously, Ethiopian-American relations deteriorated, and with U.S. President Jimmy Carter criticizing Ethiopia’s poor human rights record, in April 1977, the Derg repealed Ethiopia’s defense treaty with the United States, refused further American assistance, and expelled U.S. military personnel from the country. At this point, both Ethiopia and Somalia lay within the Soviet sphere and thus ostensibly were on the same side in the Cold War, but a situation that was unacceptable to President Barre with regards to his ambitions for Greater Somalia.

In the aftermath of the Derg’s seizing power, Ethiopia experienced a period of great political and security unrest, as the government battled Marxist groups in the White Terror and Red Terror, regional insurgencies that sought to secede portions of the country, and the Derg itself racked by internal power struggles that threatened its own survival. Furthermore, the Derg distrusted the aristocrat-dominated military establishment and purged the ranks of the officer corps; some 30% of the officers were removed (including 17 generals who were executed in November 1974). At this time, the Ogaden insurgency, led by the WSLF and other groups, also increased in intensity, with Ethiopian military outposts and government infrastructures subject to rebel attacks. Just a few years earlier, President Barre did not provide full military support to the Ogaden rebels, encouraging them to seek a negotiated solution through diplomatic channels and even with Emperor Haile Selassie himself. These efforts failed, however, and with Ethiopia sinking into crisis, President Barre saw his chance to step in.