Ugandan leader General Idi Amin pleaded for assistance from his friend, Muammar Gaddafi, the Libyan leader. Gaddafi responded by dispatching 3,000 Libyan soldiers, supported with tanks, artillery, and some planes. On their arrival in Uganda, the Libyan force was sent directly to battle. On March 10, 1979, the Libyans threw back a Tanzanian force that was advancing toward the Lukaya Swamps. The following day, two Tanzanian brigades attacked the Libyans from the north and south of Lukaya. Caught by surprise, the Libyans were routed and broke out in a run.

The Tanzanians advanced unopposed through the Masaka-Kampala Road and passed through towns and villages where large crowds welcomed them as liberators. The Tanzanians captured Mpigi, as well as Entebbe, where the Libyans were overwhelmed after initially putting up some resistance.

On April 10, 1979, the Tanzanian Army entered and occupied Kampala, Uganda’s capital, practically ending the war except for some small-scale fighting that would continue for the next few months. General Amin earlier had fled into exile, first to Libya, and then Saudi Arabia, where he was welcomed as a guest by his friend, King Faisal I. General Amin would live in Saudi Arabia until his death in 2003.

After the war, the remaining Libyan forces were allowed to leave Uganda, and departed by way of Kenya. For a time, the Tanzanian Army remained in Uganda to carry out peace-keeping duties until security was restored, and to oversee the Ugandan political system’s return to democracy.

However, Uganda’s transition to democracy was turbulent and wracked by bitter in-fighting and a power struggle among factions of the coalition that had helped to overthrow General Amin. Uganda, a country traditionally divided by ethnic loyalties, saw the re-emergence of regional political affiliations at the expense of a collective Ugandan nationalism.

In general elections held in December 1980, former President Obote returned to power by winning the presidential race. But charges of election fraud, the fractious political climate, and the continued militarized environment after the war, led to the formation of many armed groups that would lead the country into a new round of conflict, the Ugandan Bush War (next article).

(Taken from Uganda-Tanzania War – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 3)

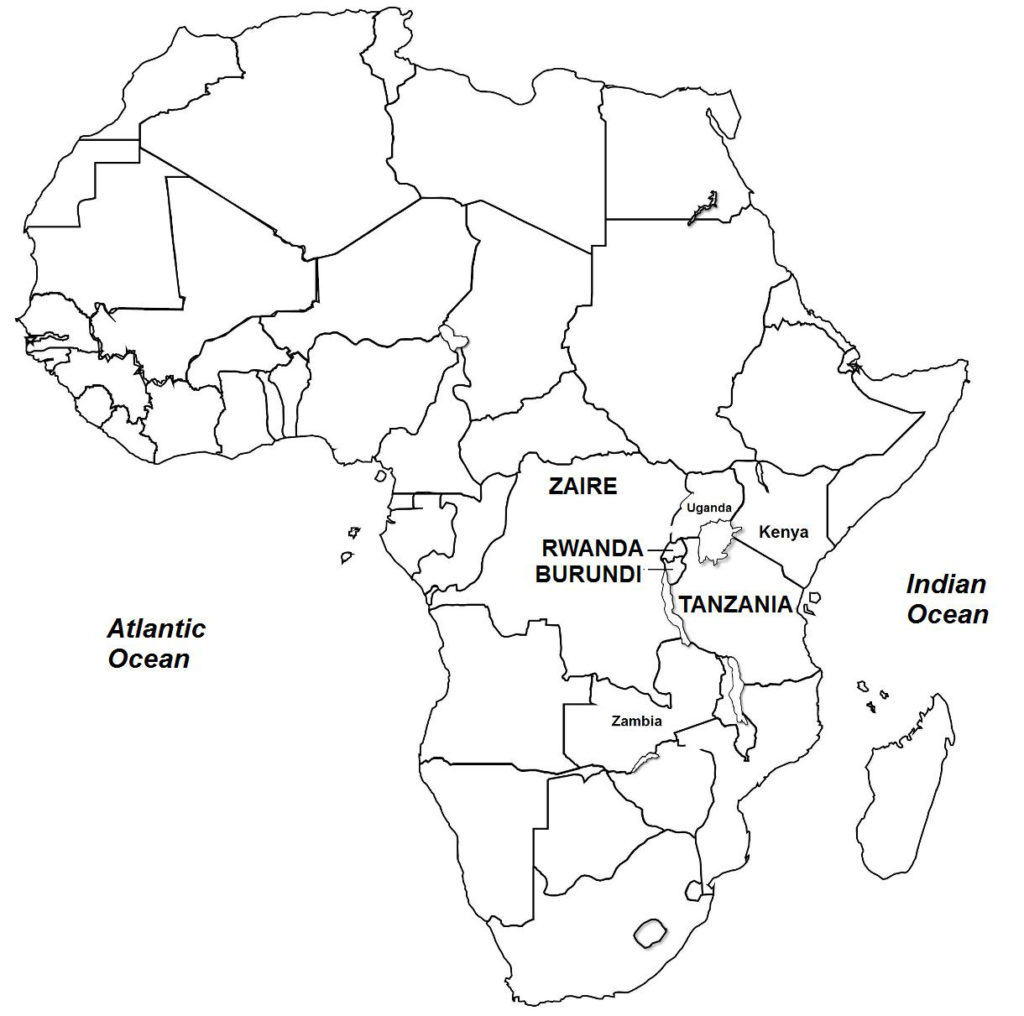

Background In January 1971, Ugandan President Milton Obote was overthrown in a military coup while he was on a foreign mission. Fearing for his safety, he did not return to Uganda but flew to Tanzania, Uganda’s southern neighbor, where Tanzanian President Julius Nyerere gave him political sanctuary. President Nyerere’s action, however, was not well received by General Idi Amin, the leader of the Ugandan coup, and relations between the two countries deteriorated.

In Uganda, General Amin took over power and established a military dictatorship, and named himself the country’s president and head of the armed forces. He carried out a purge of military elements that were perceived as loyal to the former regime. As a result, thousands of officers and soldiers were executed. General Amin then formed a clique of staunchly loyal military officers whom he promoted based on devotion and subservience to his government rather than on merit and competence. In lieu of local civilian governments, General Amin set up regional military commands led by an army officer who held considerable power. Corruption and inefficiency soon plagued all levels of government.

Military officers who had been bypassed or demoted from their positions became disgruntled. Many of these officers, including thousands of soldiers, crossed the border to Tanzania and met up with ex-President Obote and other exiled Ugandan leaders. Together, they formed an armed rebel group whose aim was to overthrow General Amin. The rebels were well received by the Tanzanian government, which provided them with military and financial support.

In 1972, the rebels launched an attack in southern Uganda and came to within the town of Masaka where they tried to incite the local population to revolt against the Ugandan government. No revolt took place, however. General Amin sent his forces to Masaka, and in the fighting that followed, the rebels were thrown back across the border.

Ugandan planes pursued the rebels in northern Tanzania, but attacked the Tanzanian towns of Bukoba and Mwanza, causing some destruction. The Tanzanian government filed a diplomatic protest and increased its forces in northern Tanzania. Tensions rose between the two countries. Through mediation efforts of Somalia, however, war was averted and the two countries agreed to deescalate the tension, and withdrew their forces a distance of ten kilometers from their common border.

The insurgency provoked General Amin into intensifying his suppressive policies, especially against the ethnic groups of his political enemies. All social classes from these rival ethnicities were targeted, from businessmen, doctors, lawyers, and the clergy, to workers, peasants, and villagers. Even members of General Amin’s Cabinet and top military officers were not spared. General Amin’s secret police, called the State Research Bureau, carried out numerous summary executions and forced disappearances, as well as tortures and arbitrary arrests. During General Amin’s eight-year reign in power, an estimated 300,000 to 500,000 Ugandans were killed.

General Amin also expelled the ethnic South Asian community from Uganda. These South Asian Ugandans were the descendants of contract workers from the Indian subcontinent who had been brought to Uganda during the British colonial period. South Asians comprised only 1% of the total population but were predominantly merchants, traders, landowners, and industrialists who held a disproportionately large share of Uganda’s economy; other South Asians were wealthy professionals, held clerical jobs, or were tradesmen.

After the expulsion, the South Asians’ businesses and properties were seized by the government and distributed to the general population in line with General Amin’s program of promoting the social and economic advancement of black Ugandans. However, many of the assets ended up being owned by General Amin’s military and political associates, most of whom had no knowledge of running a business. Soon, most of these operations failed and closed down.

As a result, Uganda’s economy deteriorated. Poverty and unemployment soared, and basic commodities became non-existent or in very low supply. Coffee beans, the country’s main export product, were required by law to be sold to the government. But as the government failed to pay or underpaid the farmers, the smuggling of coffee beans to nearby Kenya (where prices were much higher) became widespread and carried out by farmers and traders at the risk of a government-issued shoot-to-kill order against violators. Eventually, however, coffee bean smuggling operations came under the control of the army commanders themselves.

Initially, the Western media was fascinated by General Amin’s idiosyncratic behavior and outrageous statements, making the Ugandan leader extremely popular in foreign news reports. But as his brutal regime and human rights record became known, Britain and the United States, both Uganda’s traditional allies, distanced themselves and ended diplomatic relations with General Amin’s government. Uganda then turned to the Soviet Union, which soon became the Ugandan government’s main supplier of weapons. Uganda also strengthened military ties with Libya and diplomatic relations with Saudi Arabia.

By 1978, Uganda had become isolated diplomatically from much of the international community. Despite outward appearances, the government was experiencing growing dissent from within. A year earlier, General Amin was nearly ousted in a coup carried out by high-ranking government officials, underscoring the growing political opposition to his rule.

Then in November 1978, Uganda’s Vice-President, Mustafa Adrisi, was wounded in a car accident, which might have been an assassination attempt on his life. Adrisi’s military supporters, which included some elite units, broke out in mutiny.