On March 13, 1979, the New Jewel Movement (NJM), a Marxist-Leninist group, seized power in Grenada, overthrowing the government of Prime Minister Eric Gairy in a nearly bloodless coup. The coup’s leader, Maurice Bishop, took over government authority, declared himself head of the “People’s Revolutionary Government”, suspended Grenada’s constitution, and thereafter ruled by decree in a dictatorship. The “Jewel” in New Jewel Movement is the acronym for “Joint Endeavor for Welfare, Education, and Liberation”.

(Taken from U.S. Invasion of Grenada – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 2)

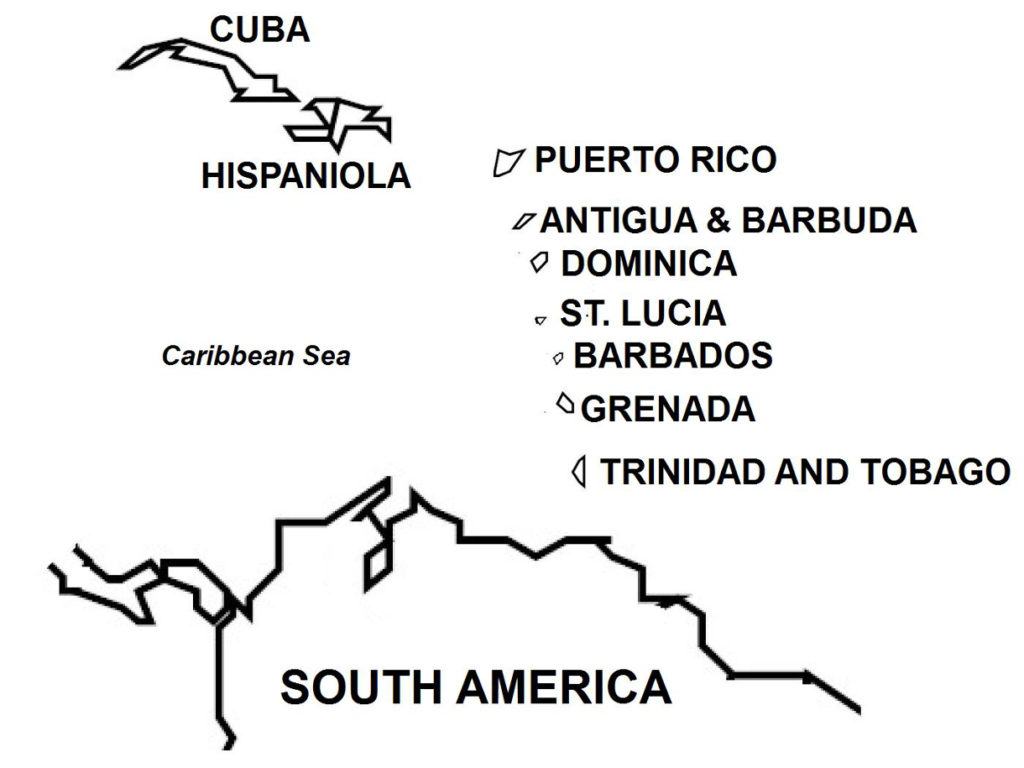

Background Grenada is a small island country located in the southeastern section of the Caribbean Sea (Map 36). In 1974, the country gained its independence from the United Kingdom and thereafter experienced a period of political unrest starting with the contentious general elections of 1976. After the 1976 elections, a government was formed, which imposed repressive policies to curb political opposition and dissent. Then on March 13, 1979, communist politicians staged a coup that overthrew the government.

A socialist government was formed led by Maurice Bishop, who took the position of prime minister. The new government opened diplomatic relations with communist countries. In particular, Grenada became allied with Cuba and the Soviet Union, and supported their foreign policy initiatives. Prime Minister Bishop dissolved the Grenadian constitution, banned elections and multi-party politics, and suppressed free expression and all forms of dissent.

The government began many social and economic projects, which ultimately proved successful. For instance, sound financial policies allowed Grenada’s economy to grow and reduce the country’s dependence on imported goods. The government made major advances in upgrading the educational system, health care, and socialized housing programs. Public infrastructure projects were implemented.

Despite being officially socialist, the Grenadian government maintained its traditional ties to the West. Grenada retained its British Commonwealth membership, with Queen Elizabeth II as its symbolic head of state, and the British-inherited position of Governor General being maintained. Western foreign investments were encouraged, and investors from the United States, the United Kingdom, and Canada – among other countries – operated freely in the islands. Foreign tourists, who brought in substantial revenues to the local economy, were welcomed by the Grenadian government.

However, hardliners in Grenada’s communist party (called the New Jewel Movement) disagreed with Prime Minister Bishop’s double-sided policies. They demanded that he step down from office or agree to rule jointly with staunch communist party members. Prime Minister Bishop rejected both suggestions. On October 12, 1983, the communist hardliners overthrew the government in a coup, and Prime Minister Bishop and other high-ranking government officials were arrested and jailed. A military council was formed to rule the country.

Widespread street protests and demonstrations broke out as a result of the coup, as Prime Minister Bishop was extremely popular with the people. The protesters demanded that Bishop be set free. Bishop’s military captors acquiesced, and released the ex-prime minister. But in the ensuing chaos, government troops opened fire on the protesters, killing perhaps up to a hundred persons. Bishop and other top government officials were rounded up and executed by firing squad.

The U.S. administration of President Ronald Reagan, following the events in Grenada with grave concern, believed that Cuba had planned the overthrow of Prime Minister Bishop’s moderately socialist government in order to install a staunchly communist regime. The United States believed that Cuba would then take full control of Grenada. Four years earlier in 1979, when the Grenadian communists took over power, U.S. president Jimmy Carter’s government had moved diplomatically to isolate Grenada by stopping U.S. military support and discouraging Americans from travelling there.

But President Reagan took an aggressive approach against Grenada: he ordered joint military exercises and mock amphibious operations in U.S.-allied countries in the Caribbean region. He also warned of Soviet-Cuban expansionism in the Western Hemisphere. Of particular concern to President Reagan was the construction of an airport at Point Salines at the southern tip of Grenada, which the U.S. military believed would be a Soviet airbase because its extended runway could land big, long-range Russian bombers. The U.S. government surmised that the Soviets planned to use Grenada as a forward base to supply communists in Central America, i.e. the Sandinista government in Nicaragua and the communist rebels in El Salvador and Guatemala. Increasing the Americans’ suspicion was the presence of Cuban construction workers at the Point Salines site – after the war, the U.S. military learned that these were Cuban Army soldiers.

However, the Grenadian government insisted that the Point Salines facility would be used as an international airport for commercial airliners. As diplomatic relations deteriorated between the United States and Grenada, President Reagan ordered the evacuation of American citizens living in Grenada, the majority of whom were the 800 medical students enrolled at the American-owned St. George’s University. The U.S. government feared for the safety of the students, as the Grenadian Army had posted soldiers at the school grounds and a nighttime curfew had been imposed on the island, with a shoot-to-kill order imposed against violators. As commercial flights to Grenada were cancelled already, President Reagan decided that the U.S. Armed Forces should implement the evacuation.

On October 21, 1983, the Organization of Eastern Caribbean States asked the United States to intervene militarily in Grenada, fearing that the political instability in that island could spread across the Caribbean region. The United States Armed Forces then revised its plan from an evacuation to include an invasion of Grenada.

Invasion The United States identified three targets for the invasion: Point Salines, Pearls Airport in Grenville, and St. George’s. Just before dawn on October 25, 1983, a battalion of U.S. Rangers was airdropped at the Point Salines Airport construction site. The soldiers succeeded in taking control of the facility. The Rangers originally were planned to be landed by plane; the plan was aborted when U.S. reconnaissance detected that the airport runway was littered with obstacles. The anti-aircraft gunfire from the Grenadian defenses was silenced by strikes from U.S. helicopter gunships. The U.S. Rangers soon secured and cleared the Point Salines Airport site, allowing American planes to land more troops, weapons, and supplies.

A few hours later, U.S. troops located St. George’s campus and evacuated the American students back to the United States. Advancing from Point Salines, U.S. forces met some sporadic resistance, including a Grenadian attack using Soviet armored carriers. By nightfall, the Americans were in control of much of the Point Salines outlying areas and had captured hundreds of Grenadian troops and the Cuban soldiers who had posed as construction workers. The prisoners were turned over to the Eastern Caribbean peacekeeping forces that had arrived to carry out policing duties.

Occurring simultaneously with the Point Salines invasion, U.S. Marines landed in Grenville, located east of the island (Map 37), which was taken with little opposition. Pearls Airport then came under American control, where more troops, weapons, and supplies were landed by U.S. planes. American forces then moved north and east from Grenville, extending the occupation zone.

At St. George’s, Grenada’s capital (Map 37), U.S. helicopters carrying the American attack forces arrived in broad daylight and were met by heavy anti-aircraft fire from Grenadian ground forces that had been alerted by the landings earlier in other parts of the island. However, the American helicopters landed successfully at St. George’s. There, U.S. Navy SEALs who were tasked to rescue Grenada’s Governor General at his residence were pinned down by enemy fire. A U.S. air attack on two Grenadian military garrisons in the capital suffered some helicopter gunship losses and many U.S. soldier casualties. That night, U.S. Marines were landed amphibiously north of St. George’s. The Marines soon relieved the beleaguered U.S. Navy SEALs and helped rescue the Governor General, who was flown out to safety.

By morning of the invasion’s second day, American air and ground attacks, including armored and artillery units that had been brought to the front, overcame fierce resistance from the two Grenadian garrisons at St. George’s. More American medical students were found at the Grand Anse campus located six kilometers south of the capital; they were flown out to safety by U.S. military helicopters.

By the third day, Grenadian resistance had ceased, with fighting ending in all combat sectors. The American operation to capture Caviligny Barracks, however, met a bizarre accident when four U.S. helicopters crashed, killing many soldiers on board.