On June 6, 1944 (also called D-Day), the Allied 21st Army Group launched Operation Overlord, the invasion of the French coast of Normandy. The operation was delayed by one day from its earlier planned June 5 because of a storm in the English Channel. A lull in the inclement weather encouraged General Dwight D. Eisenhower, over-all commander of Supreme Headquarters, Allied Expeditionary Forces (SHAEF), to proceed with the invasion. Meanwhile in northern France, the bad weather lulled German authorities into believing that no invasion would take place, and on June 6, at the time of the Normandy landings, many high-ranking German commanders were away from their posts and participating in military exercises elsewhere.

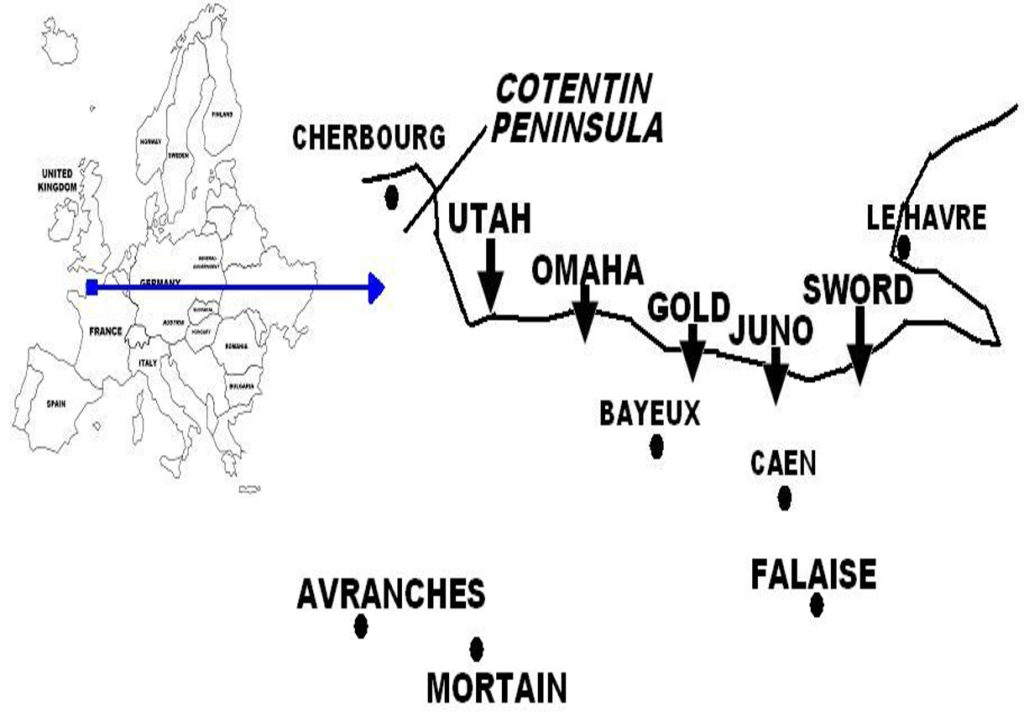

The invasion began with British and American parachute and glider units making overnight landings in Normandy on the flanks of the target area, and securing bridges, exit routes, and capturing other key objectives. In the early morning of June 6, Allied air and naval units launched a massive bombardment of the Normandy coast and the immediate interior, which was followed by the landing of the ground forces. With a massive supporting naval armada of some 7,000 vessels, including 1,200 warships, 4,100 transports, and several hundreds auxiliary vessels, Allied land forces ferried by amphibious landing crafts hit the Normandy coast at five points: in the western sector, U.S. forces in the beaches codenamed Utah and Omaha, and in the eastern sector, the British at the beaches named Gold and Sword, and the Canadians at Juno.

The British and Canadians established beachheads after encountering only moderate German resistance, while U.S. forces at Utah beach at the extreme right, facing the weakest resistance of all the sectors, also easily gained a foothold. At Omaha beach, U.S. forces met fierce enemy fire and suffered heavy casualties from the entrenched defenders occupying the high ground overlooking the beach. The Germans at Omaha Beach also comprised the veteran 352nd Infantry Division, the strongest formation in Normandy. Here, the Americans faced the real danger of being thrown back into the sea. The rapid landing of more troops and tanks, and more decisively, the bombardment of German positions by Allied warships and planes allowed the Omaha situation to ease by mid-day. By the end of D-Day (June 6), four of the five beachheads were secured, while Omaha was still being cleared and consolidated, and also still subject to distant enemy artillery fire. (Excerpts taken from World War II in Europe.)