On January 23, 1991, forces of the insurgent Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF), led by Paul Kagame, attacked the northern town of Ruhengeri, where they seized weapons from the local army barracks. They withdrew the next day when government forces arrived. Then for the next 18 months, Kagame used guerilla tactics to elude the Rwandan Army, while staging pin-prick attacks on isolated military outposts, patrols, and convoys. Despite its superiority in personnel and weapons, the Rwandan Army was unable to inflict a decisive defeat on the rebels.

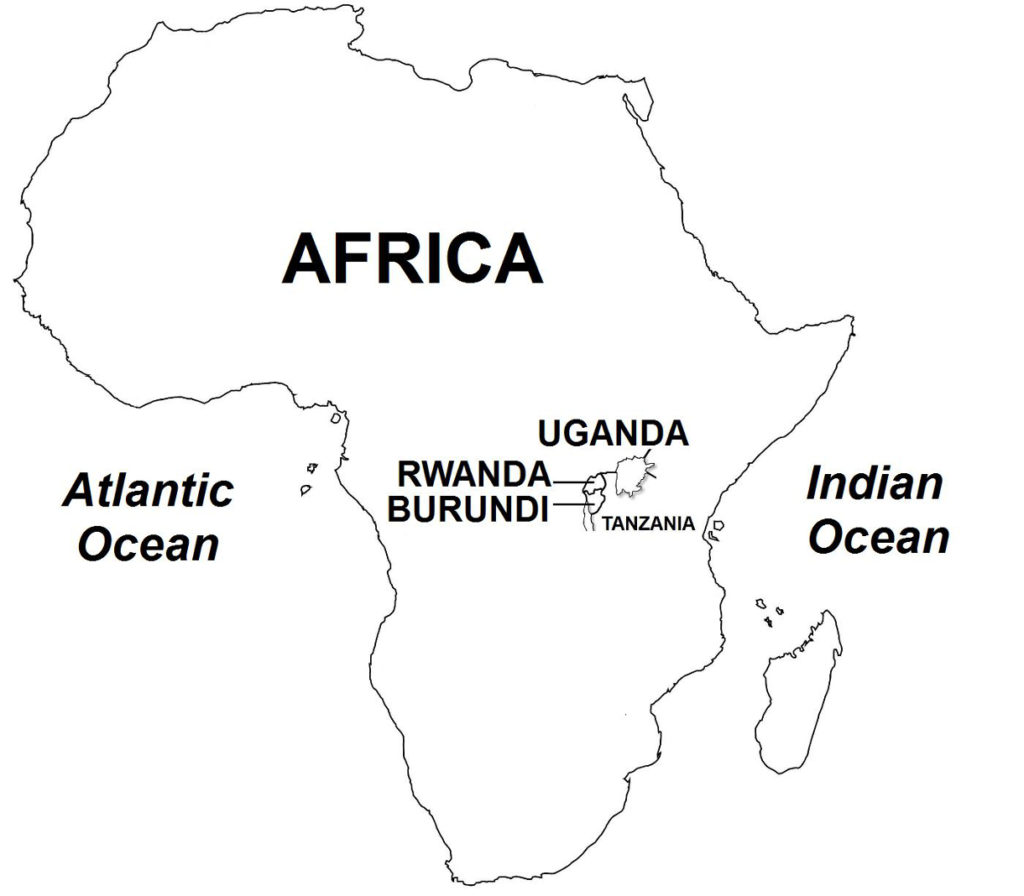

Then in June 1992, with mediation by the Organization of African Unity, or OAU, the government and Kagame signed a ceasefire agreement in Arusha, Tanzania. OAU officials arrived in Rwanda to monitor the ceasefire. Later in 1992, the government and the rebels held peace talks which, however, failed to produce a clear settlement. Powerful Hutu radicals in the Rwandan government rejected the peace process, as they were opposed to making any deals with Tutsis. These radical Hutus formed civilian armed groups, the most notorious being the “death squads” known as the Interahamwe, whose only motive was to kill Tutsis. Soon, the Interahamwe began attacking Tutsi civilians.

(Taken from Rwandan Civil War and Genocide – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 2)

Rwandan Genocide On April 6, 1994, President Habyarimina and Burundi’s head of state, Cyprien Ntaryamira, were killed by undetermined assassins when their plane was shot down by a rocket-propelled grenade as it was about to land in Kigali. A staunchly anti-Tutsi military government took over power in Rwanda. Within a few hours and in reprisal for the double assassinations, the new government unleashed the Interahamwe “death squads” to murder Tutsis and moderate Hutus on sight. Over the next several weeks, in the event known as the “Rwandan Genocide”, large numbers of civilians were murdered in Kigali and throughout the country. No place was safe; in some instances, even Catholic churches were the scenes of the massacres of thousands of Tutsis where they had taken refuge.

The attackers used clubs, spears, firearms, and grenades, but their main weapon was the machete, with which they had trained extensively and which they used to hack away at their victims. At the urging of local officials, Hutu civilians joined in the killing frenzy, and turned against their Tutsi neighbors, acquaintances, and even relatives. In many cases, the threat of being killed for appearing sympathetic to Tutsis forced many otherwise disinterested Hutus to participate.

The Rwandan Army provided the Interahamwe with a list of Tutsis to be killed, and raised road blocks to prevent any escape. The death toll in the Rwandan Genocide ranges from between 800,000 to one million; some 10% of the fatalities were moderate Hutus. The genocide lasted for about 100 days, from between April 6 to July 15, producing a killing rate of 10,000 persons a day. The speed by which it was carried out makes the Rwandan Genocide the fastest in history. (By comparison, the Holocaust in Europe during World War II, although producing a much higher death toll, was carried out over a number of years.)

During the course of the genocide, the UN force in Rwanda was ordered not to intervene by the UN Secretary General. In any case, the UN force was seriously undermanned and only lightly armed to stop the widespread violence.

The UN peacekeepers, however, managed to protect the civilians inside their zone of authority. Shortly after the violence began, foreign diplomats and their staff from the various embassies in Kigali fled the country. Other civilian expatriates were evacuated as well. The international community, including the Western powers, chose not to intervene in the genocide or misread the upsurge in violence as just another combat phase in the civil war.