On February 8, 1904, three hours before the Russian government received Japan’s declaration of war, the Japanese Navy launched a surprise attack on the main Russian Pacific Fleet anchored at Port Arthur. Fighting lasted until the next day, with the two sides’ battleships being brought into action. Russian shore batteries eventually forced the Japanese Navy to withdraw offshore, where it commenced what became a protracted blockade of Port Arthur. Although the Japanese attack on Port Arthur caused no serious losses to the Russians apart from some damage to a few ships (which were repaired), the suddenness of the war shocked the Russian government. Tsar Nicholas II particularly was incredulous that a small nation such as Japan would provoke a giant, powerful nation such as the Russian Empire.

(Taken from Russo-Japanese War – Wars of the 20th Century – Twenty Wars in Asia)

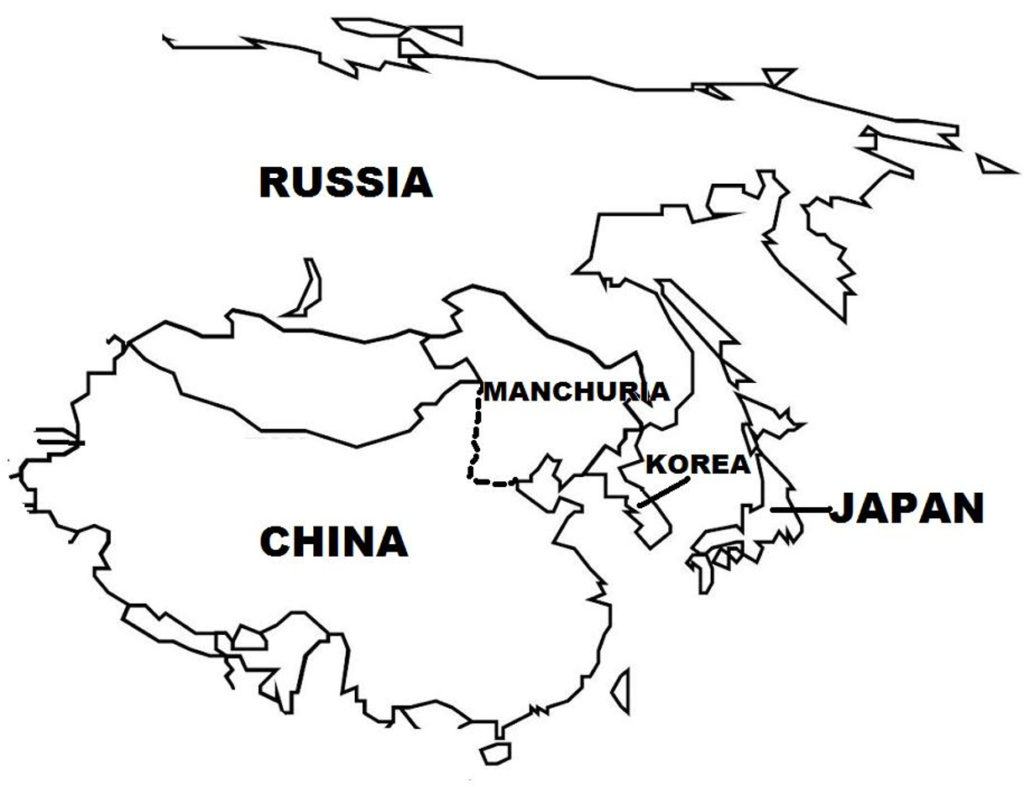

Background By the 19th century, Russia’s territorial expansion into eastern Asia was encroaching into China, which was then ruled by the weakening Qing Dynasty. Russia and China signed two treaties (the Treaty of Aigun in 1858 and the Convention of Peking in 1860), where China ceded to Russia the territory known as Outer Manchuria (present-day southern region of the Russian Far East). Then in 1896, by the terms of a construction concession, China allowed Russia to build the Chinese Eastern Railway, which would connect the eastern end of the Trans-Siberian Railway to Vladivostok, through northern Inner Manchuria (present-day Northeast China). In July 1897, construction work on this new railway line began.

In December 1897, the Russian Navy started to use the port of Lushunkou, located at the southern tip of the Liaodong Peninsula. Four months later, in March 1898, Russia and China signed an agreement, where the Chinese government granted a 25-year lease (called the “Convention for the Lease of the Liaotung Peninsula”) to Russia for Lushunkou and the surrounding areas, collectively called the Kwantung Leased Territory. The Russians soon renamed Lushunkou as Port Arthur, and developed it into its main naval base in the Far East. Port Arthur was operational all year long, compared to the other Russian naval base at Vladivostok, which was unusable during winter. Both the Chinese Eastern Railway and Kwantung Leased Territory allowed Russia to consolidate its hold over Inner Manchuria (although the region legally remained part of China), which was furthered when Russia began constructing, in 1899, the South Manchuria Railway to connect Harbin with Port Arthur, via Mukden. Also by the latter 19th century, Russia was establishing firmer political and economic ties with the Korean Empire’s weak Joseon Dynasty.

Meanwhile, Japan (which had only recently industrialized and was emerging as a regional military power) also harbored ambitions in southern Manchuria and Korea. For over two centuries (1633-1853), Japan had implemented a near total isolationist policy from the outside world. But in the 1850s, Japan was forced (under threat of military action) to sign treaties with the United States and European powers to establish diplomatic and trade relations. Seeing itself powerless against an attack by the West, Japan reunified under its emperor and then began a massive industrialization and modernization program patterned after the West, which dramatically overturned and completely altered Japan’s traditional feudal-based agricultural society. Within a period of one generation, Japan had become a modern, industrialized, and prosperous state, with the government placing particular emphasis on building up its military forces to the level matching those in the West.

In the 1870s, Japan set its sights to emulating European-style imperialist expansion (during this time, European powers were aggressively establishing colonies in Asia and Africa), and turned to its old rival, Korea. Korea, although nominally sovereign and independent, was a tributary state of China. In September 1875, after failing to establish diplomatic relations with Korea, Japan sent a warship to Korea. Using its artillery, the Japanese ship opened fire and devastated the coastal defenses of Ganghwa Island, Korea. Six months later, February 1876, Japan sent six warships to Korea, forcing the Korean government to sign a treaty with Japan, the Gangwa Treaty, which among other provisions, established diplomatic relations between the two countries, and forced Korea to open a number of ports to trade with Japan. Thereafter, European powers followed, opening diplomatic and trade ties with Korea, and ending the latter’s self-imposed isolationist policy (Korea until then had been known as the “Hermit Kingdom”).

But Japan was interested not only in opening trade with Korea, but in dominating the whole Korean Peninsula. Subsequently, Japan started to interfere in Korea’s internal affairs. Before long, the Korean ruling elite became divided into two factions: the pro-Japanese faction, comprising progressives who wanted to modernize Korea in association with Japan; and the pro-Chinese faction, comprising the conservatives, including the ruling Joseon monarchy, who were firmly anti-Japanese and wanted Korea’s national development under the tutelage of China or with the West.

The growing Japanese interference in Korea’s affairs made conflict between Japan and China inevitable. War finally broke out in the First Sino-Japanese War (1894-1895), where Japanese forces triumphed decisively. In the peace treaty (April 1895) that ended the war, China recognized Korea’s independence, (until then, Korea was a tributary state of China), China paid Japan an indemnity, and ceded to Japan the eastern part of the Liaodong Peninsula (as well as Taiwan and the Pescadores Islands). In the aftermath, Japan replaced China as the dominant controlling power in Korea.

But immediately thereafter, Russia, which also had power ambitions in southern Manchuria, particularly the vital Lushunkou (later Port Arthur), convinced France and Germany to join its cause and force Japan to return the Liaodong Peninsula to China, in exchange for China paying Japan a larger indemnity. Japan reluctantly acquiesced, seeing that its forces were powerless to fight three European powers at the same time.

Cash-strapped China sought financial assistance from Russia to pay its large indemnity to Japan. Russia released a loan to China, but also proposed a Sino-Russian alliance against Japan. In June 1896, China and Russia signed the secret Li-Lobanov Treaty where Russia agreed to intervene if China was attacked by Japan. In exchange, China allowed Russia the use of Chinese ports for the Russian Navy, as well as for Russia to build a railway line across North East China (the Chinese Eastern Railway) to Vladivostok. As the treaty also permitted the presence of Russian troops in the region, Russia soon gained full control of northeast China. Then after signing the lease for the Liaodong Peninsula, particularly vital Port Arthur, Russia gained control of southern Manchuria as well.

Meanwhile, in Korea, anti-Japanese sentiment intensified further when in October 1895, Queen Min, wife of King Gojong, was assassinated, with most Koreans blaming the Japanese, because of the queen’s strong anti-Japanese stance. Fearing for his life, Korean King Gojong fled to the Russian diplomatic office. With Russian protection, in October 1897, King Gojong proclaimed the Korean Empire, an act to symbolize the end of China’s domination of his country. Koreans were strongly anti-imperialistic and desired self-rule. Most Koreans also wanted to establish stronger ties with European countries and the United States to stop what they believed were Japan’s ambitions to take over their nation.

Undeterred, in November 1901, Japan approached Russia with a proposal: in exchange for Japan recognizing Manchuria as falling within the Russian sphere of control and influence, Russia would recognize Japan’s control over Korea. As early as June 1896, Japan and Russia had agreed to form a joint protectorate over Korea, which would serve as a buffer zone between them. But in April 1898, in another treaty, Russia acknowledged Japan’s commercial and economic interests in Korea

In January 1902, Japan and Britain signed a military pact (the Anglo-Japanese Alliance), where the British promised to intervene militarily for Japan in the event that in a Russo-Japanese war, a third party entered the war on Russia’s side against Japan. The British motive in the treaty was to curb Russia’s territorial expansionism in East Asia; for Japan, the alliance strengthened its resolve to go to war with Russia.

Subsequently, Russia appeared to be willing to compromise with Japan, even indicating its intention to withdraw from Manchuria. In March 1902, Russia and France signed a military pact, but the French government stated that it would intervene for Russia (if the latter went to war) only in a war in Europe and not in Asia. As a result, Russia would have to fight alone in a war with Japan.

A faction in the Russian government, led by the Foreign Ministry, wanted a peaceful settlement with Japan. However, Tsar Nicholas II, the Russian monarch, and the Russian military high command, pressed for continued Russian expansionism in the Far East, being confident that the Russian military, with a long history of wars in Europe, could easily defeat upstart Japan. Then when Russia did not withdraw from Manchuria, in July 1903, the Japanese envoy in St. Petersburg (Russia’s capital) issued a diplomatic protest. But in August 1903, Japan again offered Russia the proposal that in exchange for Russia’s recognition of Japan’s control of Korea, Japan would accept Russia’s control of Manchuria. In October 1903, Russia made a counter-proposal with the following stipulations: that Manchuria fell under Russia’s sphere of influence; that Russia recognized Japan’s commercial interests in Korea; and that all territory north of the 39th parallel in the Korean Peninsula would be a demilitarized buffer zone where no Russian or Japanese forces could deploy.

Each side’s proposals were unacceptable to the other, but the two sides agreed to hold talks. By January 1904, with no progress being made in the talks, Japanese representatives concluded that the Russians were stalling. Again, Japan repeated its August 1903 offer, but after receiving no reply, on February 6, 1904, Japan cut diplomatic ties with Russia. Two days later, Japan declared war on Russia.