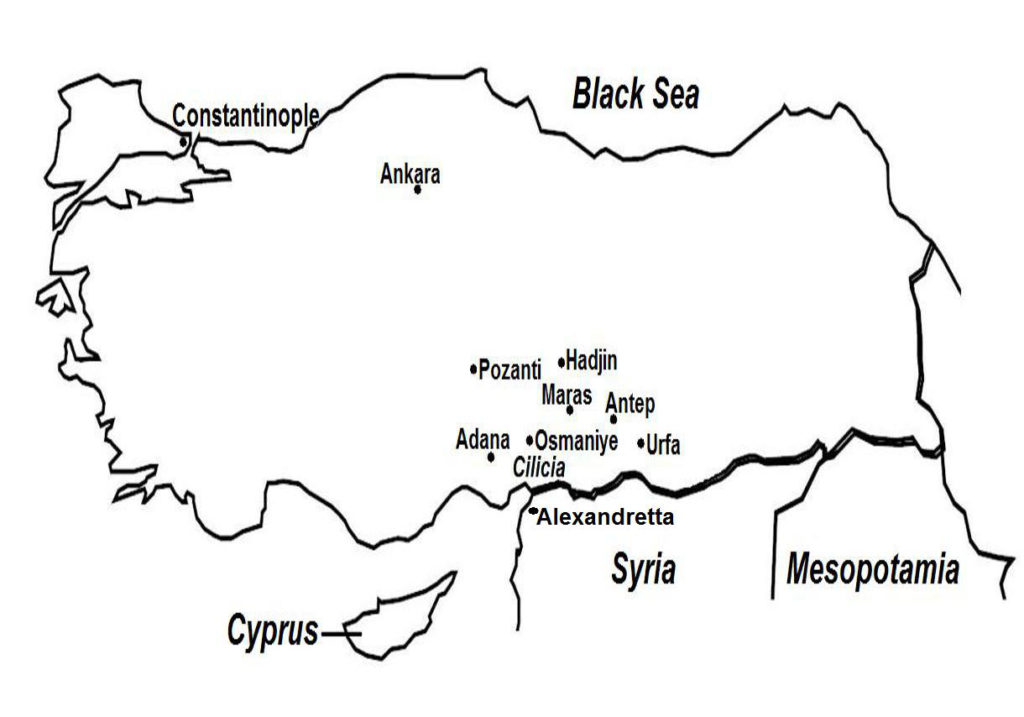

On January 20, 1920, a civilian uprising broke out in Maras. The unrest escalated when Turkish nationalist forces joined the disturbance, beginning a battle of attrition that would last for three weeks. On February 11, 1920, the French garrison, followed by thousands of terrified Armenian civilians, evacuated from the town. In their retreat to Osmaniye, hundreds of soldiers and civilians perished in the winter cold.

By early 1920, the Cilician countryside was teeming with Kemalist revolutionary elements, threatening the tenuous French hold in the lightly defended towns. Urfa came under attack in February, followed by Hadjin the next month. Fighting also broke out in Pozanti, which the French were forced to evacuate because of strong guerilla activity, and in Antep, where Turkish forces successfully resisted a ten-month siege by the French.

French rapprochement with the Turkish nationalists began in 1919, even before hostilities broke out, when French High Commissioner François Georges-Picot engaged in talks with Kemal in Ankara. By 1921, after the Turkish victory in the eastern front, France and Kemal’s nationalists opened negotiations, which led to the Cilician Peace Treaty of March 1921. The treaty, however, was not implemented.

(Taken from Turkish War of Independence – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 3)

Turkish nationalists fought in three fronts: in the east against Armenia, in the south against France and the French Armenian Legion, and in the west against Greece, which was backed by Britain.

Southern Front Also known as the Franco-Turkish War, the southern front resulted from the French occupation of southern Anatolia. Under the war-time Sykes-Picot Agreement, France had been guaranteed the lands that constitute modern-day Syria and Lebanon; the French concession extended north to southeastern Anatolia and the region of Cilicia. With the Ottoman Empire’s capitulation, the British forces who were occupying these areas at the end of World War I yielded them to the French. The French also occupied Constantinople (together with the British and Italians), Eastern Thrace (together with the Greeks), and two Ottoman ports on the Black Sea.

Another war-time treaty, the 1916 French-Armenian Agreement, allowed France to organize the French Armenian Legion, a majority-ethnic Armenian military force tasked to assist the French in the war, in exchange for France’s promise to support Armenian nationalists in Cilicia in their struggle for independence from Ottoman rule. After the war, French military authorities deployed the French Armenian Legion in Cilicia. And with its other ally, the Republic of Armenia in the east gaining independence in May 1920, France moved to fulfill Armenian aspirations for a Cilician state as well as bring the whole region under the French sphere of influence. French authorities encouraged the return to Cilicia of the Armenian refugees (from World War I) to Cilicia, as well as immigration of other ethnic Armenians; some 170,000 Armenians heeded the call.

From the outset, however, French rule in Cilicia faced many problems, foremost from the local Turkish population who resisted what was perceived as occupation by a foreign force. Bands of Kemalist nationalists soon were operating in the countryside, inciting anti-French sentiments among Turkish and Arab residents and recruiting fighters for newly formed guerilla groups.

The local Ottoman Army garrisons, before leaving, turned over their firearms to the local population and also left behind large quantities of weapons and ammunitions that were hidden away by Turkish residents. The (Ottoman) local civilian government, which the French retained to carry out regular public duties, secretly supported and conspired with the Turkish nationalists. Even the newly formed local police force was infiltrated by nationalist sympathizers.

An attempt by French authorities to return Cilician lands to repatriated Armenians met strong opposition, as Turkish locals, who now occupied the properties, refused to relinquish possession. Even so, most Armenians did not venture into the Cilician countryside for fear of their lives, preferring to remain in the coastal cities where the French military presence was strong. A law requiring the surrender of all loose firearms also was ignored by the Turkish population. And the raised French and Armenian flags in public places drew indignation among local residents.

The French did not succeed in establishing a strong military presence in Cilicia, even with the support of the British who left behind a military contingent to assist in the region’s security. The quality and quantity of weapons available to the French soldiers also were inadequate. These factors, including France’s hesitation to carry out a full occupation in contrast to the Turkish nationalists’ determination to oust the foreigners, decided the outcome in this sector of the war.