In late 1915, Yuan Shikai, President of the Republic of China, made plans to return the country to a monarchy. He reasoned that the 1911 Revolution that had toppled the Qing dynasty, and the ensuing republican government, were divisive, transitory phases, and that only a monarchy could restore order and unity to the nation. In November 1915, a “Representative Assembly” was formed to study the matter, which subsequently issued many petitions to Yuan to become emperor. After pretending to refuse these petitions, on December 12, 1915, Yuan accepted, and named himself “Emperor of the Chinese Empire”. Yuan’s reign, as well as the country’s return to a monarchy as the “Empire of China”, was set to commence officially on January 1, 1916, when Yuan would perform the accession rites.

(Taken from China (1911-1928): Xinhai Revolution, Fragmentation, and Struggle for Reunification – Wars of the 20th Century – Twenty Wars in Asia)

Yuan Shikai in Power From the outset, tensions existed between the pro-Sun groups, led by the Tongmenhui, and President Yuan and his supporters. To counter Yuan’s power base which was in the north, on February 14, 1912, the provisional Senate voted to make Nanjing the capital of the republic. However, two weeks later, mutinous Beiyang Army units rioted in Beijing. Yuan, who most likely masterminded the disturbance, announced that he would remain in Beijing to guard against future unrest. The provisional Senate thus reconvened, and in another vote taken in April 1912, named Beijing as the capital of the republic.

President Yuan soon gained full control of government, and appeared intent on extending his powers. To counter Yuan and also prepare for the upcoming parliamentary elections, in August 1912, Sun’s supporters formed the Kuomintang (KMT, English: Chinese Nationalist Party), merging the Tongmenhui and five smaller organizations. In National Assembly elections held in December 1912-January 1913, the KMT won a decisive victory, taking the most number of seats in both legislative houses over its rivals, including the pro-Yuan Republican Party.

Song Jiaoren, a leading KMT politician who had campaigned strongly against Yuan and had vowed to reduce Yuan’s powers through legislation, appeared headed to become Prime Minister, and thus would form a new Cabinet. But in March 1913, he was assassinated, perhaps under Yuan’s orders. When the newly elected National Assembly convened, the KMT-dominated legislature moved to enact measures to curb Yuan’s powers, and prepared to formulate a permanent constitution and hold national elections for the presidency. Yuan now moved to destroy the political opposition, while his opponents in the south grew more militant – as a result, China began to fracture politically.

In July 1913, many southern provinces rose up in rebellion (sometimes called Sun Yat-sen’s “Second Revolution”), this time against Yuan. The Beiyang government (as the government in Beijing was called during the period 1912-1927) was militarily prepared, as Yuan had recently received a foreign loan which he used to build up his Beiyang Army. In September 1913, Yuan’s forces crushed the rebellion, and captured the insurgent strongholds in Nanchang and Nanjing, and forced Sun and other KMT leaders to flee into exile abroad.

In October 1913, the now intimidated National Assembly elected Yuan as president of the republic for a five-year term. Yuan proceeded to break up all political opposition, first removing, coercing, or bribing KMT provincial officials. Then in November 1913, he dissolved the KMT and expelled KMT legislators from the National Assembly. As these expulsions caused the legislature to fail to reach a quorum to reconvene, in January 1914, Yuan dissolved the National Assembly altogether. In its place, Yuan formed a quasi-legislative body of 66 of his supporters, who drew up and passed a “constitutional compact”, a new charter which replaced the 1912 provisional constitution, and which gave Yuan unlimited powers in political, military, foreign affairs, and financial policy decisions. In December 1914, Yuan’s presidential tenure was extended to ten years, with no terms limits –Yuan now ruled as a dictator.

Then in late 1915, Yuan made plans to return the country to a monarchy. He reasoned that the 1911 Revolution that had toppled the Qing dynasty, and the ensuing republican government, were divisive, transitory phases, and that only a monarchy could restore order and unity to the nation. In November 1915, a “Representative Assembly” was formed to study the matter, which subsequently issued many petitions to Yuan to become emperor. After pretending to refuse these petitions, on December 12, 1915, Yuan accepted, and named himself “Emperor of the Chinese Empire”. Yuan’s reign, as well as the country’s return to a monarchy as the “Empire of China”, was set to commence officially on January 1, 1916, when Yuan would perform the accession rites.

Widespread protests broke out across much of China. Having experienced great repression under the Qing dynasty, the Chinese people vehemently opposed the return to a monarchy. On December 25, 1915, the military governor of Yunnan Province declared his province’s secession from the Beiyang government, and prepared for war. In rapid order, other provinces also seceded, including Guizhou, Guangxi, Guangdong, Shandong, Hunan, Shanxi, Jiangxi, and Jiangsu. The decisive showdown between Yuan’s army and forces of the rebelling provinces took place in Sichuan Province, where rebel forces (under Yunnan Province’s National Protection Army) dealt Yuan’s army a decisive defeat. During the fighting, Beiyang generals, who also opposed Yuan’s imperial ambitions, did not exert great effort to defeat the rebel forces. In fact, Beiyang Army commanders had already stopped supporting Yuan. Furthermore, while the foreign powers recognized the Beiyang regime as the official government over China, Yuan’s planned monarchy received virtually no international support. Isolated and forced to postpone his accession rites, Yuan finally abandoned his imperial designs on March 22, 1916. His political foes then also pressed him to step down as president of the republic. Yuan died three months later, in June 1916, with his crumbling government already unable to hold onto much of the country.

Fragmentation, Warlordism, and Struggle for Reunification After Yuan’s death, China fragmented politically, and entered into a long period of warlordism. Provinces and regions fell under the control of a military strongman, called a warlord, who ruled virtually independent of, or were only nominally subservient to the Beiyang government. China’s central government in Beijing practically ceased to exist.

The origin of warlordism can be traced to the Qing’s military reforms, which focused on strengthening provincial armies (rather than on building up a single centralized national army), and the period of Yuan’s consolidation of power. Yuan had given the local civilian governments the power over the military, thereby producing civilian-military administrators.

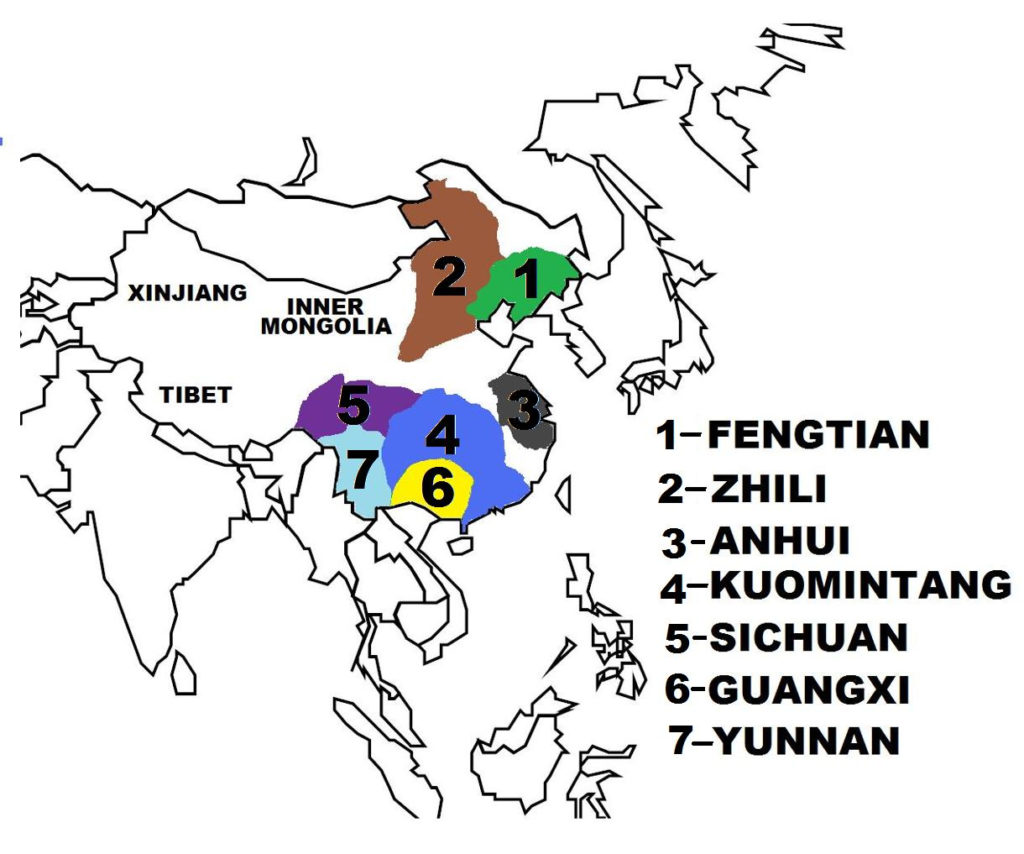

Hundreds of warlords appeared across China. They had varying strengths and control over local, provincial, or regional jurisdictions. Individual warlords, even the most powerful, did not have enough power to defeat all the other warlords, and achieve their ultimate goal of reunifying China. Consequently, warlords often banded together to form regional cliques. Dozens of such cliques formed and ruled vast regions.

Even then, all the warlords acknowledged that whoever of them controlled Beijing had the greatest authority. This was so for a number of reasons: the Beiyang government continued to be recognized by the foreign powers as the legitimate authority in China, it could apply for foreign loans, and it collected customs duties.

The Beiyang Army itself also fragmented into three competing warlord cliques: Anhui clique, Zhili clique, and Fengtian clique. These three cliques became the most powerful of the warlord groups, and subsequently vied with each other for control of Beijing, either through political maneuverings or outright warfare. This period of internecine strife in China is known as the Warlord Era, spanning the years 1916-1928.